Written by Terrance d’Ambrosio, Director of Imaging Services and Ryn Marchese, Marketing Manager

November 2023

The 390th Memorial Museum sits on the grounds of the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona. Established in 1943, the 390th bomb group of the U.S. Army Air Forces became an essential component of the Allies’ strategic bombing mission against Germany and occupied Europe. The Museum’s collection of aircrafts, artifacts, and oral histories honor the legacy of those who served in the 390th and related Bomb Groups.

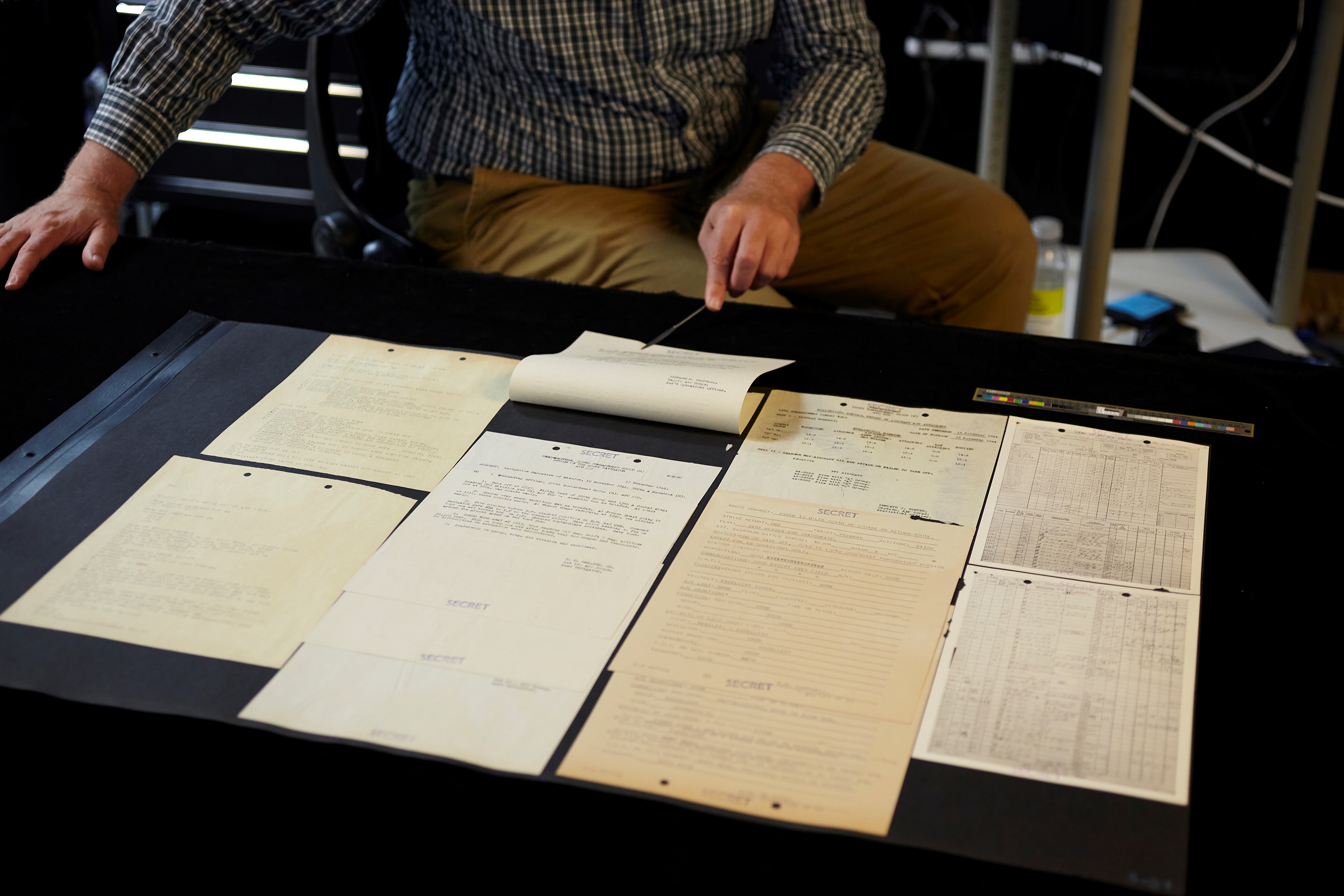

In 2020, the Museum sent five oversized scrapbooks to the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) for digitization. Each scrapbook measured 24” x 36” inches and was compiled by Colonel Joseph A. Moller, a Commanding Officer of the 390th Bomb Group of the Eight Air Force in WWII. The albums include a wide variety of documents attached to their pages, from photographs and maps, to ephemera and textual history of the Group. Through these assembled materials the scrapbooks document the personal experiences of the pilots, flight crews, and ground crews of the 390th, both during and after the war. This article explores the considerations and methods that NEDCC Senior Collections Photographer David Joyall used to digitize these challenging objects at the high quality they deserved.

|

|

WHAT IS AN OVERSIZED OBJECT?

In the context of digitization for preservation, NEDCC considers an object “oversize” both in terms of its intrinsic handling requirements and the unique imaging approach needed to achieve a high-resolution image that will record all its fine detail. To capture these details, NEDCC uses overhead cameras to digitize all of the cultural heritage materials that it works with, and even the highest resolution camera available in the lab (a 100MP sensor at the time) has limits to the area it can capture, particularly when factoring in the resolutions prescribed by preservation imaging standards like FADGI (Federal Agency Digitization Guidelines Initiative). When an object’s physical size exceeds the camera’s frame size (in this case, ~20” x 28” at 400 pixels-per-inch), NEDCC’s oversize imaging workstation steps in to help.

NEDCC’s XY Table

Rather than the large ‘sheet fed’ scanners that are often used to digitize oversize objects, NEDCC uses a custom-designed workstation that ensures the safety of the object while offering much greater flexibility than a scanner would. The workstation consists of a 4’ x 8’ table on two sets of rails that allow it to move along two axes (hence its informal name, the X-Y Table) while maintaining perfect parallelism with the camera. In practice, the oversize object is placed on the table, then the table itself is moved under the camera. This lets the photographer fully capture the object by using multiple, overlapping images, given that it’s too large to capture in a single image. This approach has several advantages, from minimizing handling to achieving consistent illumination (which is important for subsequent steps in the workflow). It also allows collections photographers to digitize particularly fragile or complex oversize objects, such as the 390th Museum’s scrapbooks.

IMAGING THE 390th SCRAPBOOKS

These particularly large and complex scrapbooks thankfully had one feature that facilitated digitization, they were bound using a ‘screw and post’ method. This style of binding, a more secure cousin of a common three-ring binder, holds the pages in place using posts and screws. The posts thread through holes punched along one edge of each album leaf, and fasteners screw into each post to attach the front and back boards and thereby secure the leaves in the binding structure. The advantage of this binding style, at least in the context of digitization, is the ease of un-binding it.

Given this opportunity presented by the binding, the first step towards digitizing the 390th scrapbooks was for Senior Collections Photographer David Joyall to first discretely collate/number the leaves to prevent any misordering once they were dis-bound and then re-bound, and then remove the screws and gently lift the leaves from the posts. This essentially left Joyall with individual flat objects, which reduced stress on the album leaves that would have been caused during imaging. It also improved the quality of the images captured from the pages by minimizing both distortion and possible variation in lighting that can occur when imaging a three-dimensional object.

Joyall proceeded to image each album leaf with the aid of the XY table and its rail system. Because of the leaves’ size, each page required four separate images to both fully capture the page and provide enough overlap between images so that they would easily ‘stitch’ together later in the workflow. With the assistance of the XY table, the collections photographers can assume consistent illumination and static distance to the camera from image-to-overlapping-image, variables which are also critical to successful stitching workflows.

When digitizing oversize objects using a camera, ‘stitching’ essentially refers to software tools that detect visually similar content across multiple image files, and then align the images based on that content – ‘stitching’ them together. This process aims to create a seamless, full-resolution re-creation of the original object, with no misalignments of content or variations in tone or color from segment to segment. For this project, photographers used Adobe Photoshop’s photomerge tool to stitch the four images comprising each album leaf. The software, alongside the photographer’s careful staging of the album leaves and the precision of the XY table’s design, produced generally excellent results across all 500+ album pages, requiring minimal editing and avoiding the need to re-photograph any of the pages.

COMPLEX OBJECTS

While imaging the scrapbook pages presented its own challenge, given their size and quantity, the complexity of the scrapbooks added another layer for the photographers to overcome. As with so many of the scrapbooks NEDCC images, the 390th Museum’s had numerous pages with complex objects attached. These objects ranged from multi-page documents layered together and tipped-in along the top edge, to letters folded and secured inside envelopes, to bi-folded cards and multi-page pamphlets and newspapers. So not only did the photographers have to capture (and stitch) the recto (front) and verso (back) of every scrapbook page, but they also had to image the recto and verso of every complex object attached to the page. In most cases, an album page required just a few extra images to capture the content of a single complex object, but some pages needed dozens of additional images, and one page layered with newspapers required more than 120 images to fully capture its contents.

By the end of the digitization project, the photographers had produced more than 540 stitched images of the scrapbook pages and an additional 650 images from the objects attached to their pages. It is an epic digitization feat that the scrapbooks more than deserve given their importance to the Museum and the significance of the story they tell.

Digitization represents a significant endeavor undertaken by the 390th Memorial Museum to enhance the accessibility of its object catalog, archives, personnel records, and mission database. As a result, previously challenging-to-handle materials are now readily available to both the museum staff and their audiences as the 390th’s story continues to be told.