Introduction

Mold can pose a serious threat to cultural heritage collections as well as to human health. An active outbreak can spread quickly, causing irreversible damage to collections materials. Both active and inactive mold can pose a health risk to those working with contaminated materials.

For most institutions, mold is a familiar problem on a small scale. Fortunately, most institutions have never experienced a major (collection-wide) outbreak. Dealing with such an outbreak can be overwhelming at first—but there are basic and tested methods to help an institution recover. This leaflet will address how to safely assess mold and respond to an outbreak (large or small), as well as steps you can take prevent future outbreaks.

HEALTH RISKS & SAFETY PRECAUTIONS

- Exposure to mold can cause allergic reactions or respiratory symptoms, even in those not prone to allergies. A reaction may be immediate or delayed. Symptoms can include runny nose, itchy/runny eyes, sneezing, cough/congestion, skin rash, and aggravation of asthma.[i]

- Allergies to mold can develop as the result of overexposure. Allergies may be severe and debilitating.

- Immunocompromised individuals should NOT handle mold or work in areas contaminated with mold, as these persons are more likely to have a severe reaction or invasive infection.[ii] Invasive infections can be life-threatening.

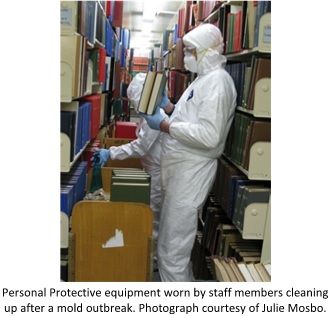

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should be worn by all individuals working with mold to prevent adverse health effects. The level of PPE required will depend on the scale of the problem.[iii] PPE should include:

- protective clothing – an apron, lab coat, or disposable Tyvek® hazard suit

- disposable gloves – nitrile gloves are preferred because they allow for a more tactile experience

- respiratory protection – approved for use with mold, i.e. a disposable N, R, or P-95 mask, half-face, or full-face respirator with particulate cartridges. Staff should be fit-tested to ensure proper protection[iv]. Ensure that masks have a good seal and are donned and removed properly.

- goggles – non-vented googles provide the best protection

identifying MOLD

Before attempting to handle or clean materials, it is essential that you determine if the damage is indeed mold – and if the mold is active or inactive. The source and status of the problem will dictate the course of action to be taken.

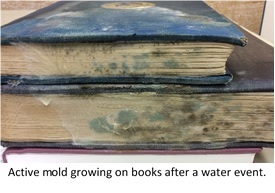

Active Mold

Active Mold

Active mold is actively growing and may feel wet or smear when touched. A musty or “earthy” smell may also be present. Mold growth typically radiates out from a central point, and the edges may have a white, hairy appearance. Active mold can spread quickly and is more likely to cause allergic or respiratory symptoms. Do not attempt to clean active mold. Active mold must first be contained and deactivated. See Responding to Active Mold.

Inactive Mold

Inactive mold is dry and powdery, and a musty smell may or may not be present. Inactive mold is simply dormant and may become active again if subjected to the right environmental conditions. Many individuals experience allergic symptoms in the presence of inactive mold. Cleaning inactive mold will reduce the possibility of future outbreaks and will make items safer to handle. See Cleaning Inactive Mold.

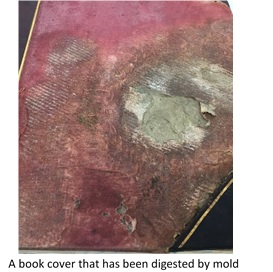

Mold can stain paper, and stains may be apparent even after visible mold has been removed. Staining is usually permanent.

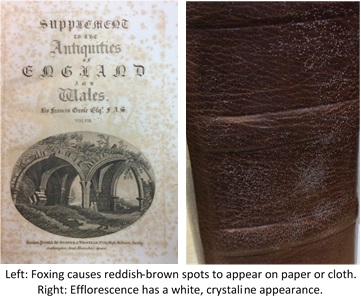

Other Problems

Other types of damage commonly mistaken for mold include dirt, foxing, and efflorescence. Foxing is characterized by reddish-brown spots that appear on paper. Efflorescence appears when fats and salts in leather or heavily starched cloth crystalize and form a precipitate. Efflorescence has a white, crystalline appearance. Both problems can be caused by high levels of humidity. While unsightly, these problems are harmless and are not a cause for concern.

RESPONDING TO ACTIVE MOLD

The actions recommended below are basic stabilization techniques that can be implemented in-house for small to moderate outbreaks. The complexities of dealing with a large number of moldy (or wet) materials will usually require outside assistance from an experienced mold remediation vendor. See Working With Mold Remediation Vendors.

The amount of materials that can be dealt with in-house will depend on the extent of the damage, available staffing, and available space and equipment. Consult with a conservator or preservation professional if you have questions about the salvage process or if additional conservation treatment is necessary.

NOTE: The following steps are numbered for convenience. The process may not always unfold in exactly this order, and some of these activities will occur simultaneously.

For salvage of wet materials, see NEDCC leaflet 3.6 Emergency Salvage of Wet Books and Records.

1. Implement safety protocols for all individuals working with mold.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should be worn to prevent adverse health effects. PPE should include:

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should be worn to prevent adverse health effects. PPE should include:

- protective clothinge. an apron, lab coat, or disposable Tyvek® hazard suit

- disposable gloves – nitrile gloves are preferred because they allow for a more tactile experience

- respiratory protection approved for use with mold, i.e. a disposable N, R, or P-95 mask, half-face, or full-face respirator with particulate cartridges. Staff should be fit-tested to ensure proper protection[iv]. Ensure that masks have a good seal and are donned and removed properly.

- goggles – non-vented goggles provide the best protection

2. Isolate the affected items, collection, or area.

- Quarantine individual items by moving them to a clean area that has a relative humidity below 55%. Do not seal a moldy book inside a plastic bag if it will not be frozen, because this will create a microclimate that will encourage mold growth. If desired, items can be placed in clean boxes or wrapped in paper to prevent the transfer of mold spores while in quarantine. Label and date wrapped items to aid in identification.

- Wet or actively moldy items should be frozen until drying and/or cleaning can commence. Mold will normally grow on wet materials within 48 hours (sometimes sooner) and will grow rapidly thereafter. If you know you cannot treat or attend to affected material within 48 hours, it is best to freeze it. This will inhibit further mold growth until you have a chance to clean or dry the material. Do not freeze photographs, audio-visual materials, leather bound books, or vellum/parchment. See Step 5.

- In the case of a large mold outbreak where it is impractical to move whole collections, the area should be sealed off from the rest of the building to the extent possible (including isolating air circulation from the affected area).

3. Determine the cause of the mold growth. You need to know what is causing the problem so that additional outbreaks can be avoided.

Look first for an obvious source of moisture, such as a water leak. If there is no obvious source of moisture, use a monitoring instrument to measure the relative humidity in the affected area. If the humidity is elevated, there might be a problem with the HVAC (heating, ventilating, and air conditioning) system, or the area might be subject to higher humidity for another reason, e.g. shelves placed against an unsealed outside wall or poor air circulation. Also look for accumulations of dust and dirt that might provide a food source for mold.

Initiate repairs or resolve the problem as soon as possible. If the problem cannot be resolved quickly, salvage the collections and frequently monitor the area for additional mold growth.

4. Take steps to modify the environment so that it is no longer conducive to mold growth.

- Moisture is needed for mold growth. Reducing the humidity below 55% is essential to stopping most mold growth.

- Mop up and/or use a wet-dry vacuum to remove any standing water.

- Bring in dehumidifiers as needed, but be sure that a mechanism is in place to drain them periodically so they do not overflow. The size of dehumidifier needed will be determined by the square footage of the space. Be sure air circulation is isolated in that space to prevent a small dehumidifier from trying to lower the RH for an entire building.

- Bring in fans to circulate the air and open the windows (unless the humidity is higher outside).

- Reduce the temperature in the area to below 70°

Do not rely on your own impression of climate conditions. Use your existing dataloggers or a thermo-hygrometer (inexpensive models can be purchased at any hardware store) to monitor temperature and relative humidity, and record the measurements in a log several times a day.

5. Deactivate any active mold growth.

Do not attempt to clean active mold on collections materials, as this may facilitate the spread of mold and/or cause staining.

The goal in deactivation is to make the mold go dormant – the stage that is appears dry and powdery rather than soft and fuzzy. Once inactive, it is possible to remove visible mold more easily (and safely).

If the items are small in number, place them in the freezer compartment of a home refrigerator, in a chest freezer, or in a commercial freezer. If possible, make arrangements for commercial freezer storage before an emergency arises since there may be restrictions on storing moldy items in a freezer that normally holds foodstuffs. Institutions may wish to purchase a dedicated freezer that is used only for wet, moldy, or pest-infested materials.

To prevent items from sticking together, wrap them in freezer paper or waxed paper, or place them in a plastic bag. Label and date each item to aid in identification.

Items should be frozen for at least 24 hours. Allow items to defrost before proceeding with cleaning. Remove items from plastic bags prior to defrosting to prevent creating a microclimate that will lead to further mold growth.

Wet materials will need to be dried prior to cleaning. See NEDCC leaflet 03-06 Emergency Salvage of Wet Books and Records.

6. Once mold has been deactivated, clean the affected items as described below under Cleaning Inactive Mold.

7. Thoroughly clean and dry the space where the mold outbreak occurred.

Cleaning may be done in-house or by a company hired to provide cleaning and/or dehumidification. If working in-house, wipe shelves down with a bleach, Lysol, or similar solution. Allow all cleaned surfaces to dry completely before returning any materials. If a musty odor lingers in the room, the culprit may be carpets and pads that have also become moldy. These will need to be replaced. If the odor is not coming from carpeting or furnishings, the odor may be temporary. If the odor lingers, the problem that initiated the mold may not be repaired. It is also a good idea to have the HVAC system components (heat-exchange coils, ductwork, etc.) cleaned and disinfected if they were the cause of the problem.

8. Return materials to the affected area.

Materials must be clean and dry, and any mold deactivated, before they are returned to the affected area. Return materials only after the area has been thoroughly cleaned, dried, and the cause of the mold outbreak has been identified and dealt with.

9. Monitor conditions in the affected area.

Take daily readings of temperature and relative humidity, and be sure that the climate is moderate. It is particularly important to keep humidity below 55% and temperature below 70°F to ensure that mold will not reappear.

Regularly check problem areas and collections to guarantee that there is no new mold growth. Be sure to examine the gutters of books and inside the spines as these are common problem areas.

CLEANING INACTIVE MOLD

Do not attempt to clean active mold from collections materials. If mold is actively growing, it must be deactivated prior to cleaning. See Responding to Active Mold.

Do not attempt to clean friable media such as pastels, charcoal drawings, or flaking paint. Contact a conservator for assistance.

Because inactive mold can cause allergic or respiratory symptoms in some individuals, it is imperative that health and safety precautions are followed.

Avoid quick and easy solutions such as spraying Lysol on objects or cleaning them with bleach wipes as these methods are often ineffective and may also cause additional or unforeseen damage. Instead, follow these steps:

1. Wear Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). PPE should include:

- protective clothing. g. an apron, lab coat, or disposable Tyvek® hazard suit

- disposable gloves – nitrile gloves are preferred because they allow for a more tactile experience

- respiratory protection approved for use with mold, i.e. a disposable N, R, or P-95 mask, half-face, or full-face respirator with particulate cartridges. Staff should be fit-tested to ensure proper protection. Ensure that masks have a good seal and are donned and removed properly.

- goggles – non-vented goggles provide the best protection

2. Work in a well-ventilated area.

- If possible, work in a ducted fume hood that vents outside. A ductless fume hood with a HEPA filter may also be used.

- If a fume hood is not available, it is preferable to work outside (weather permitting).

- If you must work indoors and do not have access use a fume hood, work in front of a window with a fan that draws air outside. Close off the room from other areas of the building (including blocking the air circulation vents). This is similar to creating negative air pressure.

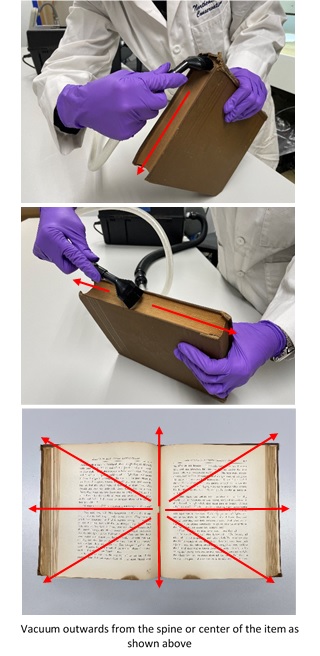

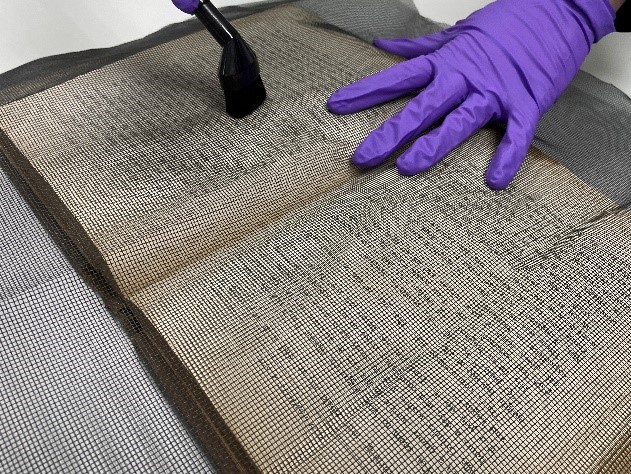

3. Remove visible mold with the aid of a HEPA vacuum. A normal vacuum will simply exhaust the spores out into the air. If a HEPA vacuum is not available, you must work outside to prevent recontamination of the space.

|

|

| HEPA vacuum with variable speed settings | Micro tools are useful for vacuuming bound volumes |

If possible, select a vacuum with a variable speed control that allows you to reduce the suction. A universal micro tool kit can be purchased for use with any vacuum with a hose attachment. The micro attachments aid in cleaning bound volumes.

If possible, select a vacuum with a variable speed control that allows you to reduce the suction. A universal micro tool kit can be purchased for use with any vacuum with a hose attachment. The micro attachments aid in cleaning bound volumes. - When vacuuming, avoid direct contact with the item, as the suction can easily damage weakened materials, and vacuum attachments may cause abrasions. Instead, hover over the object.

- For bound volumes, always work outwards from the spine or center (note the red arrows on the photos below), taking care not to catch the edge of the page.

- A soft brush can be used to loosen mold or dirt as needed. Lightly brush the mold off the surface of the item and into a vacuum nozzle. Use a light touch to prevent the mold from being permanently embedded into the fibers of the paper or textile.

- Very fragile items such as brittle paper and textiles can be vacuumed through a fiberglass window screen held down with weights. Alternatively, a brush attachment completely covered on the outside with cheesecloth can be used to guard against loss of detached pieces.

- Clean brushes, vacuum attachments, and screening in a 1:1 solution of water and bleach after use. If possible, use only dedicated brushes and attachments for mold remediation.

- When disposing of used PPE, cheesecloth, screening, vacuum bags, or filters, seal them in plastic trash bags and remove them from the building.

A soft brush can be used guide mold or debris towards the vacuum nozzle A fiberglass window screen can be held in place with a

light weight to protect fragile items when vacuuming

WORKING WITH MOLD REMEDIATION VENDORS

The amount of materials that can be dealt with in-house will depend on the extent of the damage, coupled with available staffing, space, and equipment.

An institution will need outside assistance under certain circumstances:

- If a large portion of the collection (i.e. more than 100 items or 10 document boxes) is affected by the mold outbreak

- If the HVAC system and the building are also infected with mold

- If the building and furnishings are affected

- If health concerns prevent staff from working with moldy items

- If a large numbers of items are wet and cannot be dried within 48 hours.

Particularly in the case of a hazardous mold outbreak or an infected HVAC system, it is essential to make sure that the building is safe for occupancy by staff. There are a number of companies experienced in working with cultural collections that can assist institutions with recovery. See the Disaster Assistance page on NEDCC’s website for a list of vendors and additional resources.

In addition to mold remediation, a disaster recovery company can assist with freezing and drying wet books, cleaning buildings and furnishings, and cleaning HVAC systems. In the case of a severe infestation of mold and/or an infestation that poses health risks to staff, it may be necessary to test the indoor air quality before staff return to the building.

In the past, mold-infested collections were often treated with fumigants. Ethylene oxide (ETO) and thymol will kill active mold and mold spores but are known carcinogens; other chemicals that have been used are less effective. Any of these chemicals can have adverse effects on both collections and people, and none will prevent regrowth. For some collections, it will even make them more susceptible. Due to the potential for damage, fumigants should not be used directly on or in the presence of collections except as a last resort.

Many large disaster response companies have extensive experience working with libraries and museums and are familiar with the requirements of cultural collections. If necessary, consult with a conservation or preservation professional who can assist you in choosing a service provider. Always consult with a conservation professional when salvaging materials of high artifactual value.

Mold: What it is and how it reproduces

To best prevent an outbreak and to know how to begin recovery, it is important to understand the basic lifecycle of mold and the steps needed to stop its growth.

Mold and mildew (which is mold in its early stages) are generic terms for a specific family of fungi, microorganisms that depend on other organisms for sustenance. There are over 100,000 known species of fungi. Because of the great variety of species, mold’s patterns of growth and activity in a particular situation can be unpredictable. Nevertheless, some broad generalizations of mold’s behavior are still possible.

Mold and mildew (which is mold in its early stages) are generic terms for a specific family of fungi, microorganisms that depend on other organisms for sustenance. There are over 100,000 known species of fungi. Because of the great variety of species, mold’s patterns of growth and activity in a particular situation can be unpredictable. Nevertheless, some broad generalizations of mold’s behavior are still possible.

Mold propagates by disseminating large numbers of spores, which become airborne, travel to new locations, and germinate – under the right conditions. When spores germinate, they sprout hair-like hyphae (the “fuzzy” stage) which in turn produce spore sacs that ripen and burst, releasing more spores, which starts the life cycle again.

While it is actively growing and reproducing, mold excretes digestive enzymes that alter, weaken, and stain paper, cloth, or leather. It is important to note that mold can be dangerous to people with allergies and immune problems and, in some cases, can pose a major health hazard.

Principles of prevention

To germinate (become active), spores require a favorable environment: higher relative humidity, warmer temperature, stagnant air, and a food source. If favorable conditions are not present, the spores remain inactive (dormant), and in this state they can do little damage. However, be aware that mold in its dormant or inactive state can and will reactivate if the environment changes and conditions become favorable.

The most important factor in mold growth is the presence of moisture. This is most commonly found in the air as relative humidity (RH), but can also be the natural moisture content of the object on which the mold is growing. In general, the higher the RH, the more readily mold will grow. If the RH is over 75% for one month or more at 70°F, 2 weeks at 80%, or 4 days for 90%, mold growth is likely (although some species of mold can grow at lower RH). If collections are wet as the result of a water disaster, this increases their susceptibility on both fronts: not only is the RH higher, but the moisture content of the materials has risen as well.

Other factors that will contribute to mold growth in the presence of moisture are high temperatures, stagnant air, and the location of storage. High temperatures, in conjunction with high relative humidity, will increase the rate of germination and growth of mold spores, a cycle which can then occur in as little as 24 hours. Stagnant air allows airborne spores to settle on collections. Due to this same lack of air circulation, these collections may already have increased moisture content. The resulting combination provides spores with a perfect environment for germination. Collections stored in basements or other uncontrolled spaces are most likely to be impacted by a mold outbreak. Basements tend to be damp with poor air circulation, and the likelihood that exterior walls will be cold and condense or leak is high. Collections are also more likely to be stored on the floor where rising damp is less likely to be noticed and can cause serious problems.

Mold spores, active or dormant, are everywhere. We cannot and should not attempt to eliminate all of them. They exist in every room, on every object in a collection, and on every person entering the building. The only dependable prevention strategies are:

1. Keep the humidity and temperature moderate and steady so the spores remain dormant (below 70°F and below 55% RH) and monitor to ensure the space is remaining within safe levels;

2. Maintain good air circulation in collection storage areas and monitor for stagnant pockets within a space;

3. Do not store collections in known damp spaces or those areas prone to leaks or floods;

4. Protect collections from water incidents in the first place with regular building maintenance and inspections;

5. Keep areas where collections are stored and used as clean as possible. Dust and dirt are a source of spores, both active and dormant, so housing collections in protective enclosures whenever possible helps keep them free of dust. To keep dust and spore levels low, keep windows closed;

6. Isolate incoming collections to check for mold; and

7. Change HVAC filters according to manufacturer’s recommendation and/or switch to HEPA filters if the institution has had mold outbreaks in the past.

CONCLUSION

Mold spores, active or dormant, are ubiquitous. Because it is impossible to get rid of all the spores, controlling the environment in which a spore must either thrive or become dormant is key to your preservation strategy.

If a mold outbreak does occur, remember that you have numerous opportunities and strategies to regain control. Follow the basic salvage steps listed above to identify the problem, protect staff, isolate materials, stabilize the environment, deactivate and clean the mold, and clean the space. By preparing to safely and properly react to a mold outbreak, you will be better able to protect your collections.

RESOURCES

Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI). (2017, November 20). Mould Outbreak – An Immediate Response. https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/mould-outbreak-immediate-response.html

Child, R.E. (2011, September). Mould. https://collectionstrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/mould-outbreaks-in-libraries-preservation-guide-1.pdf

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2009). Mold Remediation in Schools and Commercial Buildings. https://www.epa.gov/mold/mold-remediation-schools-and-commercial-buildings-guide-chapter-1

Florian, Mary-Lou E. (2002). Fungal Facts: Solving Fungal Problems in Heritage Collections. London: Archetype Publications.

Guild, S. and MacDonald, M. (2004). Mould Prevention and Collection Recovery: Guidelines for Heritage Collections. Canadian Conservation Institute Technical Bulletin, No 26. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/pch/NM95-55-26-2004-eng.pdf

National Park Service (NPS). (2007, August). Mold: Prevention of Growth in Museum Collections. ConserveOGram, no. 3/4. http://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/03-04.pdf

NPS. (2003, June). Choosing a Vacuum Cleaner for Use in Museum Collections. ConserveOGram, no. 1/6. https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/01-06.pdf

Reidell, S. & Smith, A. (2001, March 29). Breaking the Mold. Presentation at the Texas Library Association Conference. https://sarahreidell.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/2001_texaslibraryassoc_breakingthemold.pdf

Ritzenthaler, M. L. (2010). Preserving Archives & Manuscripts. Society of American Archivists.

ENDNOTES

[i] Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). (2013). Mold QuickCard™ https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3691.pdf

[ii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019, July 5). Invasive Mold Infections in Immunocompromised People. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/83736/cdc_83736_DS1.pdf

[iii] OSHA. (2013, November 13). A Brief Guide to Mold in the Workplace. https://www.osha.gov/publications/shib101003

[iv] American Dental Association. (2021, March 30). Conducting Respirator Fit Tests and Seal Checks. https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/coronavirus/covid-19-safety-and-clinical-resources/conducting_respirator_fit_tests_and_seal_checks.pdf?rev=3b9f400a216a447dba72d4f0b72ba6f0&hash=CBAD510A8935C9844EB0ABB26607F843

Updated 2020. Reference links updated February 2025

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs

CC BY-NC-ND