Introduction

Selection for digitization shapes the online collections built by libraries, archives, historical societies, and other cultural heritage institutions. In selecting well, institutions of all sizes and types concentrate on the parts of their collections that are best suited to digitization, make the most effective use of the technology, and meet their clients’ needs. They build online collections that are both useful and usable, and they create assets they can manage well through time.

No institution can afford to preserve or to digitize everything it owns. Some items are not worth preserving or digitizing, whether texts, photographs, sound recordings, or any other genre. Good selection decisions come through carefully assessing the physical nature and content of the original materials, the intellectual property rights connected with them, and the requirements for a technically sound, well-described, and cost-effective product that serves both users’ need for access to the content and the institution’s need to preserve the materials. Selection works best within a framework of priorities for preservation and digitization that carefully considers scale and sustainability.

Digitization and Preservation

Digital copies play an important preservation role as surrogates protecting fragile and valuable originals from handling while presenting their content to a vastly increased audience. A digital version may someday be the only record of an original object that deteriorates or is destroyed. But digitization is not preservation – it is simply a means of copying original materials. In creating a digital copy, the institution creates a new resource that will itself require preservation. Unlike microfilm and other preservation media whose longevity is assured relatively easily by proper storage, digital resources face many questions about how their continued existence, accuracy, and authenticity can be assured.

A well-designed digitization program includes not just digital capture but also appropriate care and repair of original materials and long-term management of the digital files it produces. In other words, digitization is part of a comprehensive approach to preservation and access in which all of the institution’s assets are addressed in a single, unified effort: providing repair and proper housing of original materials, creating high-quality copies in digital form where appropriate, and preserving the digital files.

|

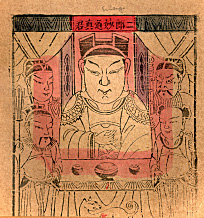

Paper god Erlang Miaodao Zhenjun |

The Starr East Asian Library at Columbia University holds a unique collection of over 200 Chinese “paper gods,” ephemeral pieces of paper printed with the image of a deity and designed to be burned during religious observances or employed as objects for household devotion. Because they are fragile and damaged, they cannot be handled safely. A stabilization and access project combines conservation, description, and digitization. The library is conserving each paper god, then scanning it, providing MARC cataloging, creating a database for online description and retrieval, and adding administrative metadata for file management over time. The master images and their metadata will eventually be submitted to a trusted digital repository. Here is the image of a god worshipped by those with sick pets — note the cat at the bottom — and the MARC record generated from the metadata.

|

Close-up of damaged Chinese paper god |

Conservator at work on Chinese |

|

Catalog |

The Selection Process

How can selectors choose among the endless materials awaiting better access through digitization? Should they concentrate on conversion of high-use documents, presentation of online exhibitions, broadening availability of national or regional heritage materials? At base, selection for digitization and preservation derives from the mission of the institution, and every institution should have a selection process in place to evaluate materials within that context and determine when digital conversion is most appropriate. Clearly stated goals for digitization and careful plans to achieve them are the starting point.

Because selection for digitization arises from a desire for better access, perhaps the most important consideration is how users will employ the digital versions, both now and in the future. Scholars, high school students, and the general public utilize online content in very different ways. What audiences does the institution hope to serve? How should content be presented to be most useful to them? What presentation and navigation tools are necessary? What metadata provide adequate description and file management? What supportive and interpretive information should accompany the content?

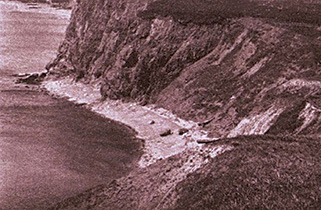

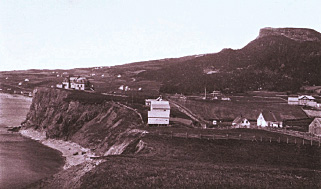

Consider this detail from a photograph published in 1905 by a geologist to document the stratigraphy of the cliffs. The whole image contains historical evidence of settlement in Canada of interest to scholars and local residents. Before choosing it the selector must consider the purpose of the digitization project: Is the target audience geologists, historians, local school students, or all of the above?

|

Detail from “Looking south from Mt Joli, Cap Canon in left foreground, Mt Ste Anne at the right,” New York State Museum Bulletin, No. 80, p. 164. Albany: New York State Education Department, 1905. |

|

Complete image, “Looking south from Mt Joli, Cap Canon in left foreground, Mt Ste Anne at the right,” New York State Museum Bulletin, No. 80, pg. 164. Albany: New York State Education Department, 1905. |

Selection Criteria

No absolute criteria guide selection for digitization, only questions to be addressed within the context of the individual institution. Each institution has its own reasons and priorities for digitization, from a national library responsible for preserving and presenting the published heritage of its citizens, to a small museum seeking publicity for its collections. The selector’s job is to apply local interpretation to a general set of selection criteria and principles, matching local goals and priorities to the materials and media in the collection.

Selection criteria help characterize materials as better or worse candidates for digitization based on content value and physical features, and they provide guidance through the logistic and infrastructure issues. The decision maker steps through a series of interconnected questions to determine whether the materials should be digitized, whether they may be digitized, and whether they can be digitized.

- Should they be digitized? Is the collection important enough, is there enough audience demand, and can sufficient value be added through digitization to make it worth the cost and effort?

- May they be digitized? Does the institution have the intellectual property rights to permit legal creation and dissemination of a digital version?

- Can they be digitized? Will digitization achieve the goals of the project, given the physical nature of the materials and their organization, arrangement, and description? Does the institution have the technical infrastructure and expertise to create digital files and make them available to users now and in the future?

Should the Materials Be Digitized?

Content Value

This is the basic question: Does the content of the material merit the expenditure of effort and resources? Specific definitions of value and importance vary from institution to institution but cluster around intellectual, historic, and physical characteristics.

- How do the materials relate to the institution’s collecting policy and to its other digital resources?

- Are they rare or unique?

- Do they provide accurate information in their subject area or contribute to broader or deeper coverage? Do they relate to areas poorly documented online?

- Is there a legal need to preserve the materials and make them widely accessible?

- Are they important for the functioning of the institution?

- Do they support current or new high-priority activities?

- Are they aesthetically appealing? Will they display well on-screen?

Value alone is not a sufficient reason for digitization. Demand from users is vital. Digitizing and mounting materials publicly is a form of publishing, and success in publishing means knowing and targeting the audience.

- Is there an active, current audience for the materials?

- Is current access to the original materials inadequate, perhaps owing to heavy use of popular items or to restricted access to fragile or costly items?

- If current demand is low, will digitization attract enough new viewers to justify the cost?

Content and demand together may be insufficient to justify the expense of digital conversion. A third important component is the value added by digitizing. What additional steps can be taken to enhance the materials’ content?

- Search capability can be added via optical character recognition (OCR) of bit-mapped images of books or other printed materials and through manual transcribing and keying of handwritten materials. Search capacity can be added to archival or graphic collections through indexing or mounting finding aids.

- Digitization can add value by combining related materials from several institutions into one virtual online collection. Such cooperative efforts can create new research and teaching tools that no single institution could achieve on its own.

|

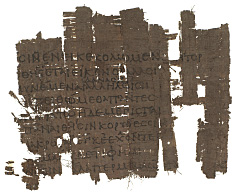

One example that began as a cooperative digitization project by Columbia and six other institutions is the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS). It has grown into a large, collections-based repository hosting information about and images of papyri, ostraka, and other early media contributed by over twenty institutions around the world. Users can move among text, translation, bibliography, description, and image. |

Fragment from Homer’s Iliad, book 14, lines 367–376 |

- Digitization can facilitate exposure of materials ordinarily kept under restricted access owing to the threat of damage, theft, or vandalism, and of materials that are difficult to use because of extreme fragility or awkward format.

|

See, for instance, Columbia’s project to stabilize 340 extremely fragile set models of productions for the Ziegfeld Follies, the Metropolitan Opera, and Broadway theaters designed by Joseph Urban and then digitize them to minimize the need to maneuver the sizable objects into the reading room. Joseph Urban, stage model of a design for the Ziegfeld Theatre, 1926–27 |

|

- Digitization may enable improvements in legibility or audibility through technical manipulation, even allowing discovery of information in ways heretofore impossible with the original materials. Enhancement of image or sound quality may, however, affect the perceived accuracy of the digital version as a replica of the original. Many experts agree on the importance of providing access to both the accurate reproduction of the original object and the enhanced or manipulated version.

May the Materials Be Digitized?

Intellectual Property Rights

The second major question is whether the institution has the legal right to digitize and mount the materials online. Intellectual property rights should be addressed early in the selection process because the institution may not be able legally to reformat the materials, or at least not be able to disseminate digital versions. While institutions do have the legal right to digitize materials that are under copyright if the purpose is preservation, the digital versions must be accessed only on the institution’s premises. Obtaining permission from rights holders takes time, can be expensive, and is not always possible.

It is relatively easy to determine whether a published work is under copyright and the name of the copyright holder, but many digitization efforts target unique archival, visual, and audio materials that are unpublished and entail complicated histories of ownership and multiple layers of authorship. Whether, and how, public access to sound files or images of these materials may be provided remains subject to legal interpretation.

In deciding whether to digitize, therefore, selectors should ask the following:

- Is the purpose of digitization purely preservation, so that dissemination is not an issue?

- If not, does the institution have the legal right to make and disseminate digital copies?

- If not, is the work or collection in the public domain and its use therefore unrestricted?

- If not, can permission be obtained from the rights holders?

Aside from copyright issues, privacy may also raise concerns. Do the materials contain personal information that should not, or cannot, be legally disseminated? On a more general level, do issues of religious, ethnic, or community sensitivity make public access to the materials problematic?

The institution should also consider its digitization projects from the rights holder’s point of view. The means and level of access that the institution is willing to provide to its own digital assets have a direct impact on display of digital versions, licensing, and related matters.

- How will the institution control access to and use of its digital assets?

- Will everyone have free, open access to the resources or will restrictions be imposed?

- Will full, high-quality digital versions be mounted? Lower-resolution versions that are undesirable for commercial uses may be too low for serious research use.

- Will the proposed level of access accommodate the type of uses the institution wants to provide to its patrons?

Can the Materials Be Digitized?

Technical Aspects

The third question asks whether the institution actually has the technical capability to capture, describe, store, and make digital versions accessible. In brief, digital conversion requires the following:

- Preparation of materials, including physical organization and/or collation, providing description and identification through cataloging and metadata, and any needed repair or conservation work

- High-quality capture of the content according to national best practices

- Creation of metadata that record technical, structural, and capture information

- Possible enhancement and manipulation, as discussed above

Significant work is also required to mount files, make them accessible, and manage them over time:

- Creating the user interface, with all the necessary searching and navigational tools

- Managing the website

- Planning for preservation of the files over the long term

All of these considerations are basic to an effective product and mean that the subject expert cannot — and indeed should not — make digitization decisions alone. For successful digitization, the institution’s technical experts on preservation, digital capture, metadata creation, web design, and digital asset management need to collaborate in making the initial selection. If there are no resident experts, working with consultants is strongly recommended. Furthermore, since each set of experts has its own vocabulary, priorities, and principles, a successful digitization program can be as much about team building as about the materials.

The technical aspects of digitization for text, images, audio, and other genres influence selection because information can be captured in many ways at many quality levels. The institution must determine whether it can provide digital versions of the quality users need.

- How will digital images and sound be used, and what level of quality does that entail? A temporary online exhibition might call for quite different quality than a site serving in-depth research.

- What features of the original must be conveyed in the digital version? What features are less important? Do viewers want a surrogate that gives a feel for the actual object, one that makes the content easier to use, or both?

- Will the digital version be of high enough quality to be useful in the future, as technology evolves?

An item’s physical characteristics affect what can be captured, stored, displayed or served, and manipulated. These start with the legibility/audibility of the original item, dimensions, and tonality. Before digitizing it is essential to know the smallest detail that must be viewed or heard for the information to be useful, whether a high degree of tonal accuracy is required, and so forth. Technical experts can then determine how the desired result can be produced, and at what cost.

A second set of issues involves assessing the possibility of damage to the original item. What is the balance between potential harm during digital conversion and potential gain from the resulting digital resources? Conservators should be included in initial planning to determine whether there is a need for treatment of fragile or valuable originals in order to stabilize them, for disbinding or other preparation, and for repairs or new housing after digitization.

A third very important issue is whether the materials are organized, arranged, and described to suit online use. It is not difficult to scan a book and keep the pages in order online, but this is not true for archival materials, slide collections, or other groups of items that lack a fixed physical order. The selector must consider how relations among parts will be retained and how users will find the individual items they want. Once online, every file requires its own identification and description. Does a detailed description exist in the form of catalog records, a finding aid, or a database? How will this information be converted to usable metadata? If the collection lacks good intellectual control, preparing it for digitization can incur significant costs. What can the institution feasibly handle in terms of preparation and intellectual control? The rule of thumb for archives and special materials is, Don’t even think about digitizing until the collection is fully arranged and described.

The fourth issue concerns the contextual framework for the digitized resources. Extensive interpretive materials often prove essential to helping people understand online resources. This kind of site involves much more work than simply digitizing original objects, because it requires development of all the information that makes up a useful and usable website.

Finally, perhaps the most difficult issue: Digitization creates new institutional assets that must be preserved. Choices made at the beginning about capture methods, metadata extent, and storage media all directly affect the institution’s ability to carry out preservation. Keeping digital files intact over the long term requires an infrastructure designed for the future.

- Is the digitized content temporary, or will it have enduring value in digital form?

- If yes, does the institution have a long-term commitment to preserving digital resources?

- Is it willing and able to develop and maintain the necessary infrastructure?

Developing Strategies and Priorities for Digitization

Having worked through all these questions, the selector now faces the cost-benefit analysis. What is the likely cost of digitization, from selection to metadata creation to digital capture to preserving files for the future? Does this cost match the anticipated benefits, given the value of the materials and the demand for digital access? How does the cost fit with the institution’s mission and goals? How much is the institution willing to spend for new modes of access, wider distribution, and enhanced assets? What are its priorities?

Experience at several institutions shows that digital capture even at high resolution consumes perhaps one-third of the cost of a digitization project. There is no financial justification for skimping on quality. Poor digital copies are a waste of money. Skimping on metadata is also a mistake. Metadata is expensive, but without it people will have trouble finding and using the digitized materials, and those who manage and preserve the files over time will have serious headaches.

Needless to say, whether digitization is worth the cost depends in part on what money is available. With a selection framework in place, the institution is ready to identify high-priority materials whenever a grant or other means of support arises. Policies and long-range plans allow the institution to articulate how it will use digitization and preservation to support its mission and build consensus about what criteria will guide the choice of projects and the growth of the program.

Digitization opens exciting opportunities for preservation and access, but this wonderful capacity for delivery of audio and visual content across the Internet is not cheap or easy to achieve. Careful selection maximizes the strengths of both traditional preservation and digital technology. Careful assessment of the institution’s goals and priorities and development of thoughtful strategies will assure that meaningful, high-quality digital versions are created, and that both original and digital assets are managed well over time.

Resources

Ayris, Paul. 1998. Guidance for Selecting Materials for Digitisation. Joint RLG and NPO Preservation Conference Guidelines for Digital Imaging. http://www.rlg.org/preserv/joint/ayris.html

California Digital Library. 2004. Collection Development Process. http://www.cdlib.org/inside/collect

Cornell University Library. 2000–2003. “Selection.” In Moving Theory into Practice Digital Imaging Tutorial. http://preservationtutorial.library.cornell.edu/selection/selection-01.html

Council on Library and Information Resources, Task Force on the Artifact in Library Collections. 2001. The Evidence in Hand. http://www.clir.org/pubs/abstract/pub103abst.html

Gertz, Janet. 1998. Selection Guidelines for Preservation. Joint RLG and NPO Preservation Conference Guidelines for Digital Imaging. http://www.rlg.org/preserv/joint/gertz.html

Hazen, Dan, Jeffrey Horrell, and Jan Merrill-Oldham. 1998. Selecting Research Collections for Digitization. Council on Library and Information Resources. http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/hazen/pub74.html

Library of Congress, Preservation Reformatting Division. 2005. Selection Criteria for Preservation Digital Reformatting. http://lcweb.loc.gov/preserv/prd/presdig/presselection.html

Menne-Haritz, Angelika, and Nils Brübach. 2005. The Intrinsic Value of Archive and Library Material. Archivschule Marburg. http://www.archivschule.de/content/292.html

National Information Standards Organization, Framework Advisory Group. 2004. A Framework of Guidance for Building Good Digital Collections. 2nd edition. http://www.niso.org/framework/framework2.html

National Library of Australia. 2006. Collection Digitisation Policy. https://www.nla.gov.au/about-us/corporate-documents/policy-and-planning/collection-digitisation-policy

Smith, Abby. 2001. Strategies for Building Digitized Collections. Council on Library and Information Resources. http://www.clir.org/pubs/abstract/pub101abst.html

Ibid. 1999. Why Digitize? Council on Library and Information Resources. http://www.clir.org/pubs/abstract/pub80.html

University of California Libraries. 1997. Selection Criteria for Digitization. https://libraries.universityofcalifornia.edu/pag/university-of-california-selection-criteria-for-digitization/

Washington State University, Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation. 2020. Strategic Digitization Goals Part 2: Digitization Selection Criteria Worksheet. https://sustainableheritagenetwork.org/system/files/atoms/file/dsc1.32.pdf

Vogt-O’Connor, Diane. 2000. “Selection of Materials for Scanning.” In Handbook for Digital Projects: A Management Tool for Preservation and Access. Maxine K. Sitts, editor. Andover, Mass.: Northeast Document Conservation Center.

Written by Janet Gertz

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs

CC BY-NC-ND