PART ONE - History of Victorian Hairwork and Background of the davenport Album

By Mary Hamilton French, Associate Book Conservator, 2020

Introduction

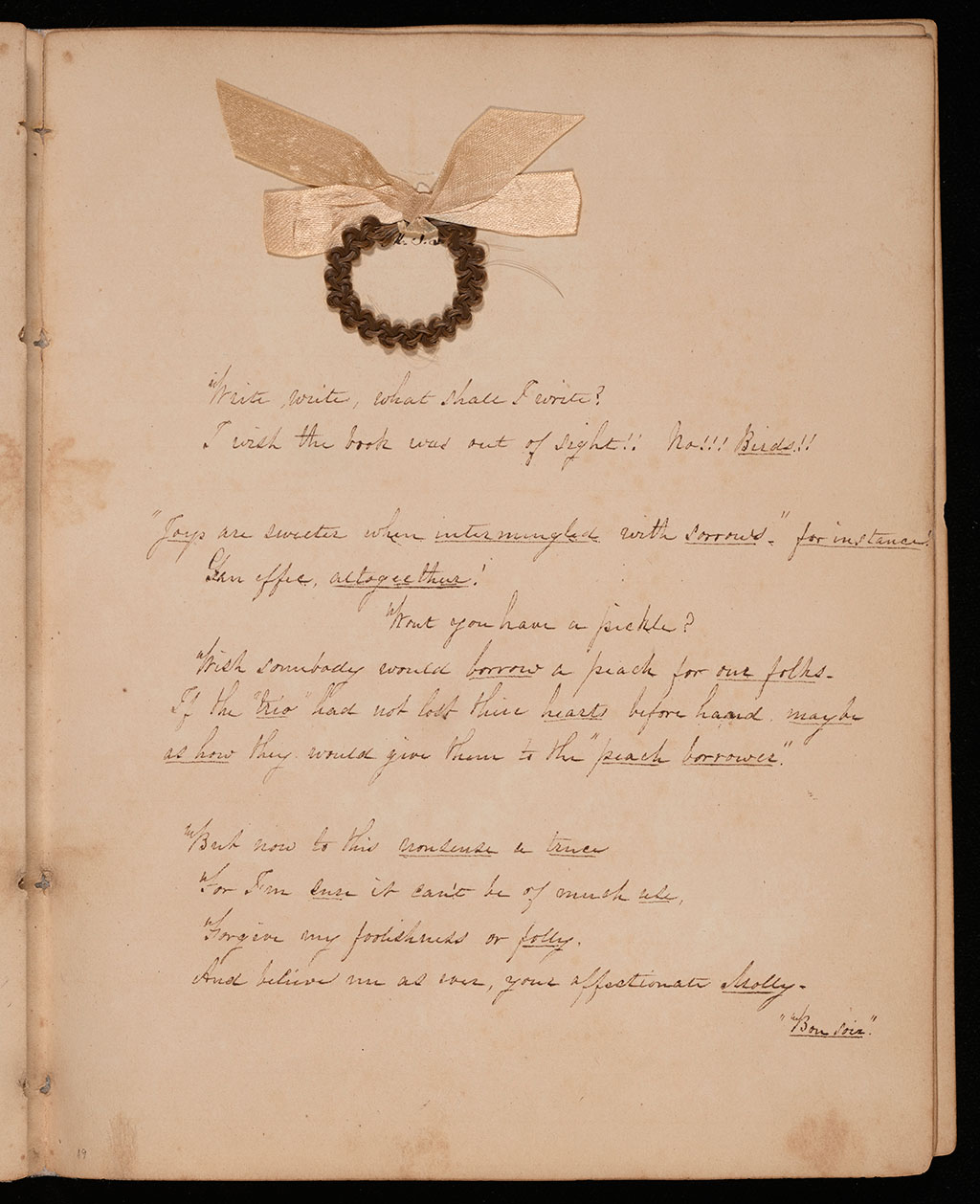

In 2019, the Davenport House Museum in Savannah, Georgia, brought a 19th-century hair album to the Northeast Document Conservation Center for assessment, conservation, and digitization. While NEDCC conservators frequently work on scrapbooks and albums, these usually contain photographs, handwritten notes and letters, and printed ephemera like postcards, concert programs, and tickets.

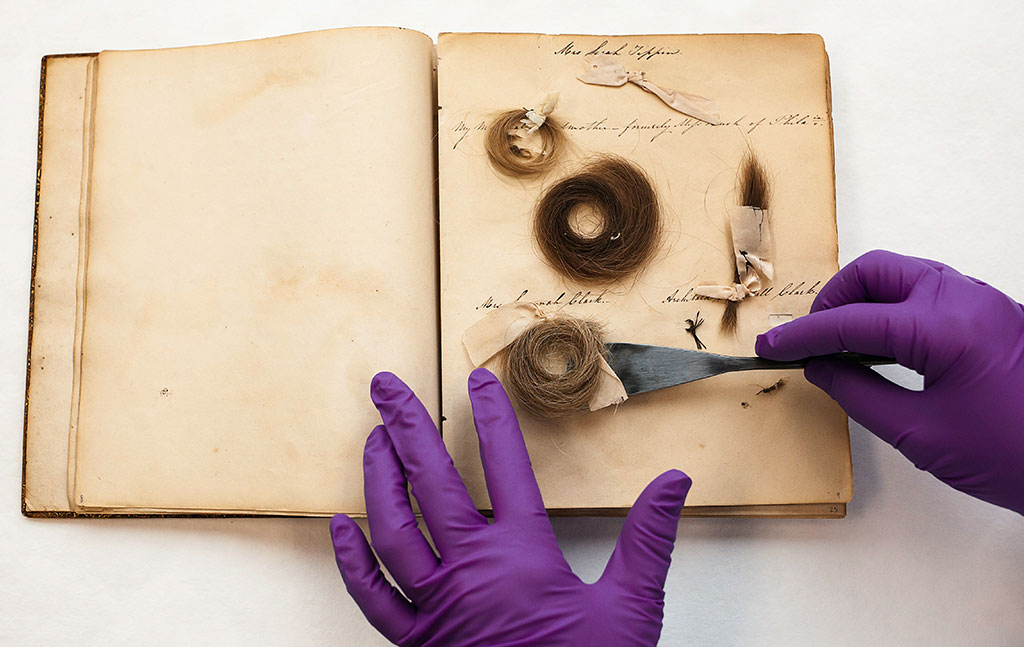

The Sarah Davenport scrapbook contained an unusual surprise: locks of human hair that Sarah had collected from her family and tied to the pages of the text block using silk ribbons. Due to the presence of this hair, which was brittle and often detached from the book, as well as the need to preserve the artefactual value of the volume, this project proved to be an interesting conservation challenge and required drawing upon elements of textile and object conservation, as well as book and paper conservation, to find a workable solution.

Because this project was so complex, this story has been split into two parts. Part One will contain a description of the album, background on Victorian hairwork, history of the Davenport family, and the ethical decision-making required by this project.

For a description of the conservation treatments carried out to the binding, hair locks, and silk ribbons, please see Part Two - Conservation Treatment and Digitization of the Album.

The album contained many complex elements, such as locks of hair and delicate silk ribbons.

The Davenport House Museum

The Davenport House Museum was built by local master builder Isaiah Davenport in the early 19th century as a home for himself, his wife Sarah, and their 10 children. In 1955, just hours before the historic house was scheduled to be demolished to pave the way for a parking lot, it was purchased by the newly-formed Historic Savannah Foundation. Over the next 7 years, the house was restored and was opened to the public as a historic house museum in the early 1960s.

The Davenport House. Image credit: Davenport House Museum.

Victorian Hairwork

As strange as it might seem today, Victorians often used human hair from friends and family to create wreaths and jewelry, commonly referred to as “hairwork.” Victorian hair albums are a rarer phenomenon than other types of hairwork and are also a culturally different phenomenon. Hair wreaths and hair jewelry were often created as an act of mourning and generally the hair was removed from the deceased prior to burial. The jewelry served as a way to keep your loved one near you as you went on with your daily life, and was also a socially acceptable fashion accessory during the official mourning period. Hair wreaths were another mourning artifact and were fashioned in the shape of a horseshoe with the open end upwards to signify ascent into heaven.

A hair brooch made with two locks of hair. Image credit: Wellcome Trust, photo number L0058632.

A hair brooch made with two locks of hair. Image credit: Wellcome Trust, photo number L0058632.

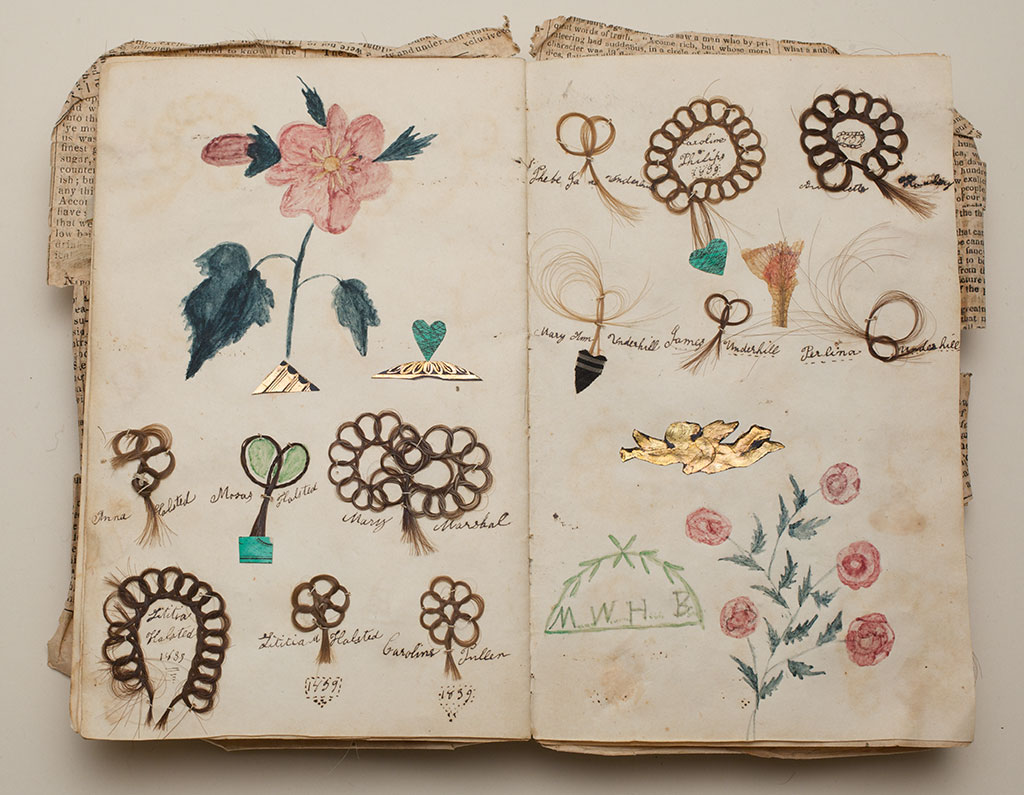

Hair albums, on the other hand, were often assembled using locks of hair from living friends and family and more closely relate to the concept of an album amicorum or friendship album. Friends exchanged locks of hair as a token of affection or sometimes remembrance if a friend was moving far away and it was unlikely that they would ever see each other again. The locks of hair were styled according to the abilities of the album creator, ranging from simple bunches tied together with string or ribbon to elaborate braided and looped creations. Asking one’s friends for a lock of hair seems almost unimaginable now, but in a time before the invention of photography, a piece of hair was the only tangible way to remember someone.

A hair album containing intricate loops of hair from friends as well as drawings and printed ephemera. Image credit: The Library Company of Pennsylvania, Friendship Album, Margaret Williams, 1839. Accession number: OBJ 846.

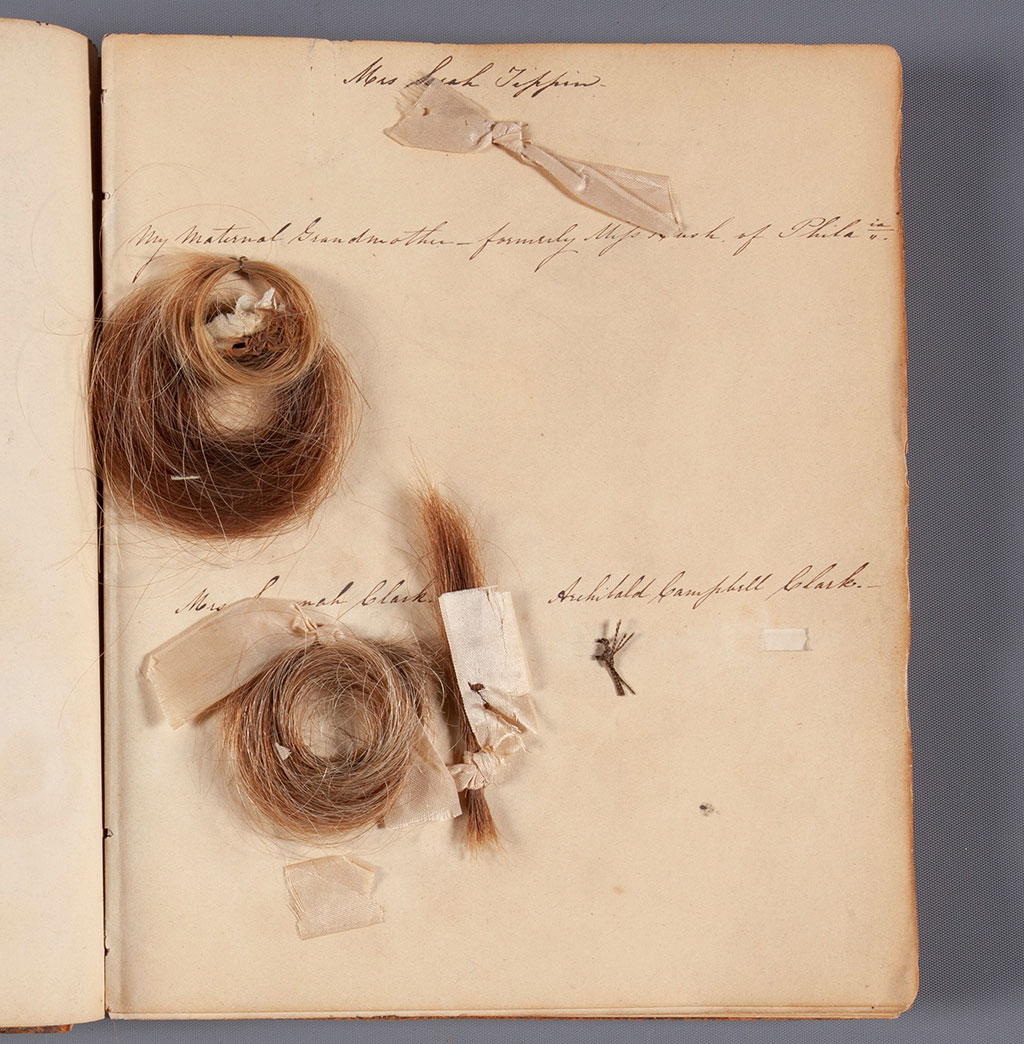

Sarah Davenport's Album

Sarah Davenport was gifted this album in 1829 by an unnamed friend. Sarah’s album has more focus on mourning than is usual for hair albums, and perhaps this is due to the fact that the album was given to her in the same year that her mother died. There are no keepsakes or signatures from friends or family and the album contains handwritten poems and anecdotes on memory, mortality, faith, youth, beauty, and love. By 1829, Sarah had already experienced a significant amount of death in her family, having suffered the loss of her husband, three of her children, her maternal grandmother, mother, and father in the preceding years.

Interestingly, the album contains locks of hair from the family members who predecease the creation of the album, in some cases by decades, so it is clear that Sarah had been collecting hair long before she ever thought to assemble it in one place. She also put locks of hair from her children, their spouses, and her grandchildren in the album, arranging them by birth order and family unit into a family tree of sorts, which was a common sorting method for familial hair albums.

Sarah Davenport’s album prior to treatment.

The Album's Condition

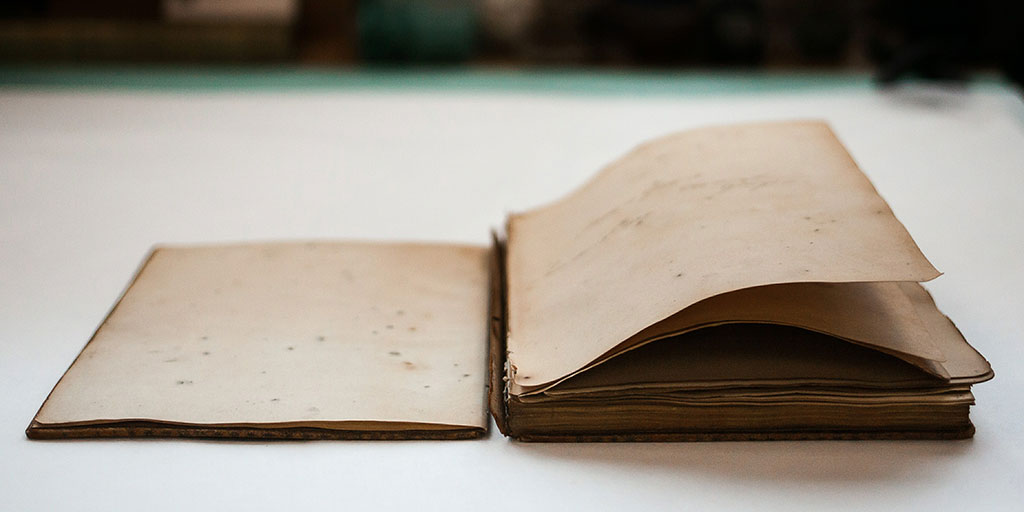

Upon arrival at NEDCC, the hair album was given a thorough assessment prior to deciding upon a treatment plan. The volume consisted of a full leather binding with blind and gold tooling on the boards and spine. There were several structural issues with the binding, including a detached front board and broken sewing in the first two sections, causing the first two sections to break free from the remainder of the text block. The likely reason for this damage was the addition of thick locks of hair throughout the first three sections which distorted the text block.

This type of damage is very characteristic of scrapbooks created from blank books that were never meant to accommodate the addition of extra materials by the reader. The text block of this album does not have any compensation stubs to account for the bulk of the hair, and this eventually strained the sewing and board attachments to the point of breaking.

Text block distortion caused by added bulk from the hair locks.

The text block consisted of sections of machine-made paper sewn through the fold onto two recessed cords. There were manuscript entries throughout the text block, although hardly anything was written beyond the first 3 sections. Locks of hair were tied with silk ribbons to the text block through slits in the support leaves. The silk ribbons were brittle and fractured, and as a result many of the locks of hair were detached from the text block and some had been permanently lost.

Detached hair locks and fragmentary silk ribbons were present throughout the album.

Historic hair tends to get more brittle as it ages, and these locks of hair – some more than 200 years old – were no exception. The most brittle locks were broken at the point where they had been tied with string and then attached to the text block with ribbons. Other locks of hair were separated into two pieces – probably not breakage, but rather due to the hairs pulling loose from the thread and ribbon over time. In addition, some support leaves were broken and had losses in the paper at the point where the locks of hair had been attached.

Because the original attachment method placed a large amount of stress concentrated on two relatively small areas – a small 1cm slit in acidic and slightly brittle paper, as well as a single compression point at the thread tied around the hair – these places bore the brunt of mechanical strain and suffered more damage than if the strain had been spread out over a larger area.

A broken stub from a now-missing hair lock.

Creating a Treatment Plan

When forming a treatment plan, it was important to consider a few ethical and logistical conservation issues. The most pressing concern was how to treat the hair so that it was not damaged further during conservation, imaging, or its future life back home at the Davenport House Museum. The hair was slightly brittle, although not alarmingly so, and it could be handled safely. The hair could therefore be remounted, but was it ethical to do so? The album had a significant amount of artefactual value stemming from Sarah’s careful arrangements of the hair and it would lose most of its meaning if the hair locks were removed and stored separately. Additionally, Sarah’s daughter, Cornelia, had created a similar album that was inspired by her mother’s and this album was still fully intact. Reattachment of the locks was a priority for the museum so that the album could function as it was originally intended and so that it could be studied in context with Cornelia’s album.

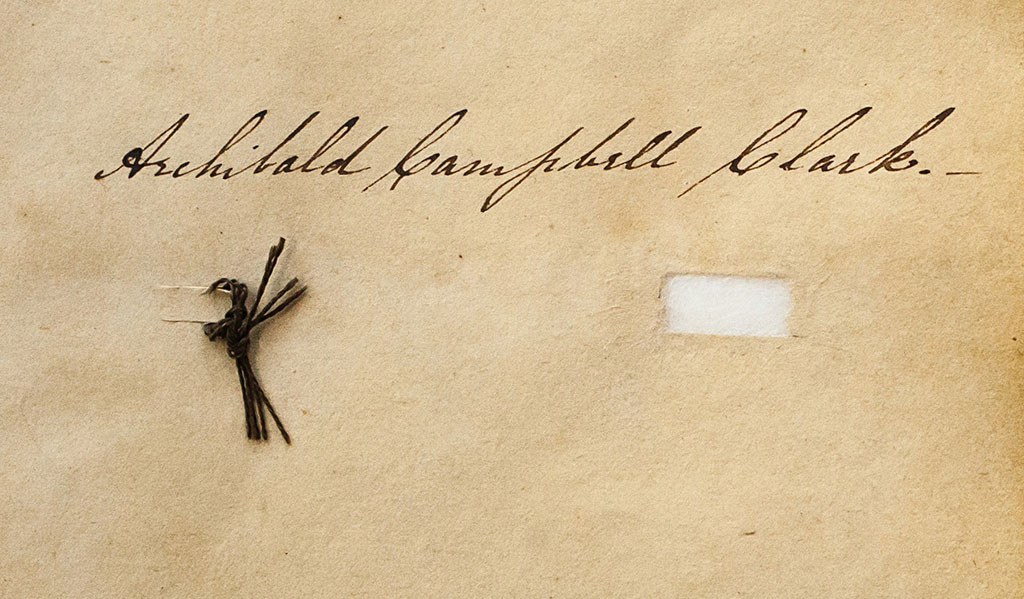

Cornelia Davenport's Album

Another point to consider was that many of the hair locks had gone missing over time and reattachment would help prevent that from happening in the future. However, it was clear that the previous attachment method was going to be unsuitable as the silk ribbons were not strong enough to hold the hair together, and it was felt that tying the hair to the support leaves using just one attachment point would rapidly cause further damage to both ribbons and locks.

Some support leaves had losses in the attachment slits due to mechanical wear from the hair’s attachment method.

Choosing a stabilization and remounting method that harmed neither the hair nor the text block was difficult. After a significant amount of research, consultation with other conservators, and thinking about the problem from a different perspective, an innovative solution based on textile and objects conservation techniques was developed.

Story Part 2

View the NEDCC Story Part 2 — Conservation of the Sarah Davenport Album for the rest of the story on the conservation of the binding, hair, and silk ribbons.

LEARN MORE

About the Davenport House Museum, Circa 1820, Savannah, Georgia

Throughout its 50+ years as a historic site, the Davenport House Museum has treated visitors to intriguing and vivid experiences centered on a legendary Savannah-centric tale of courage and determination. Visit: www.davenporthousemuseum.org

The digitized album can now be viewed on the Davenport House Museum website, allowing worldwide access to this unique book.

WATCH THE VIDEO: Associate Book Conservator Mary Hamilton French speaks about the Sarah Davenport album for the Old Stone House Museum & Historic Village.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Bexx Caswell-Olson, NEDCC Director of Book Conservation for her encouragement to develop this project into a presentation and paper; Annajean Hamel, NEDCC Lead Preparator, for helping make a sewing frame for the hair; Graham Patten, a Book Conservator at the Boston Athenaeum, for his helpful advice; and Camille Myers Breeze, Director & Chief Conservator and Morgan Carbone, Associate Conservator, Museum Textile Services for their helpful advice and for generously supplying NEDCC with textiles and thread.

Special thanks to Jeff Freeman, Davenport House Museum Assistant Director and Collections Manager, and the other Museum staff for their enthusiastic permission in letting NEDCC present this conservation project.

Story by Mary French, Associate Book Conservator