PART TWO - Conservation Treatment and Digitization of the Album

By Mary Hamilton French, Associate Book Conservator

Introduction

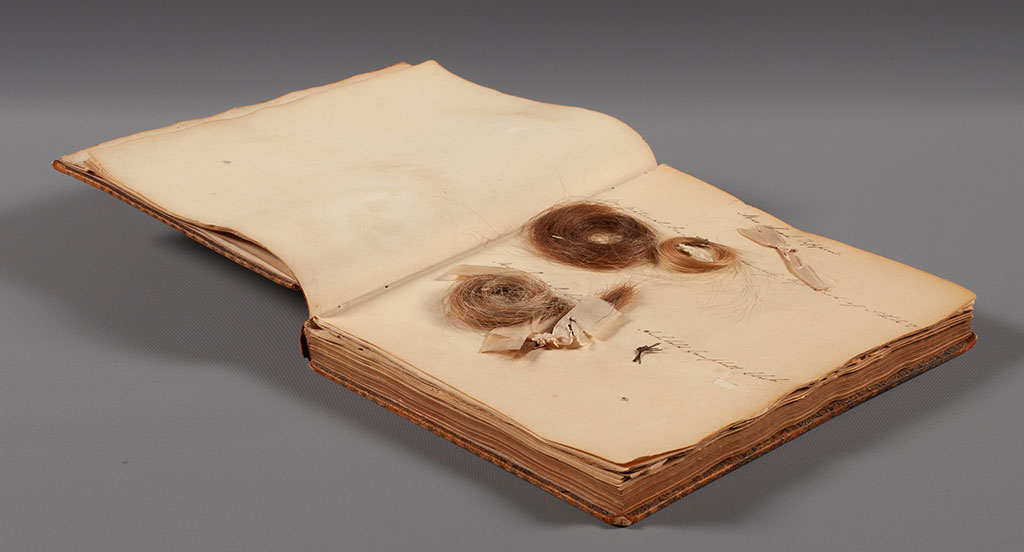

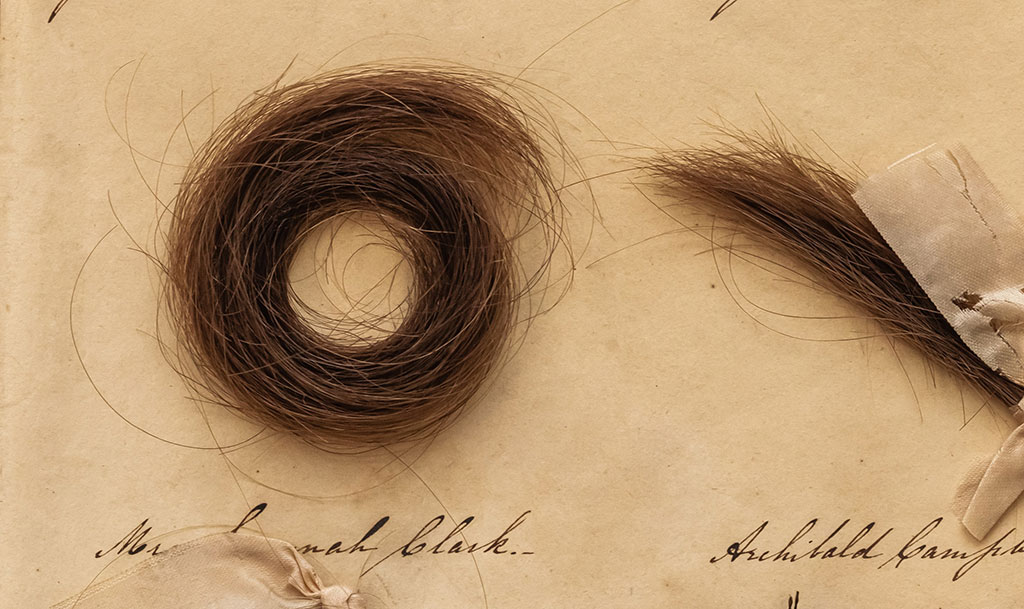

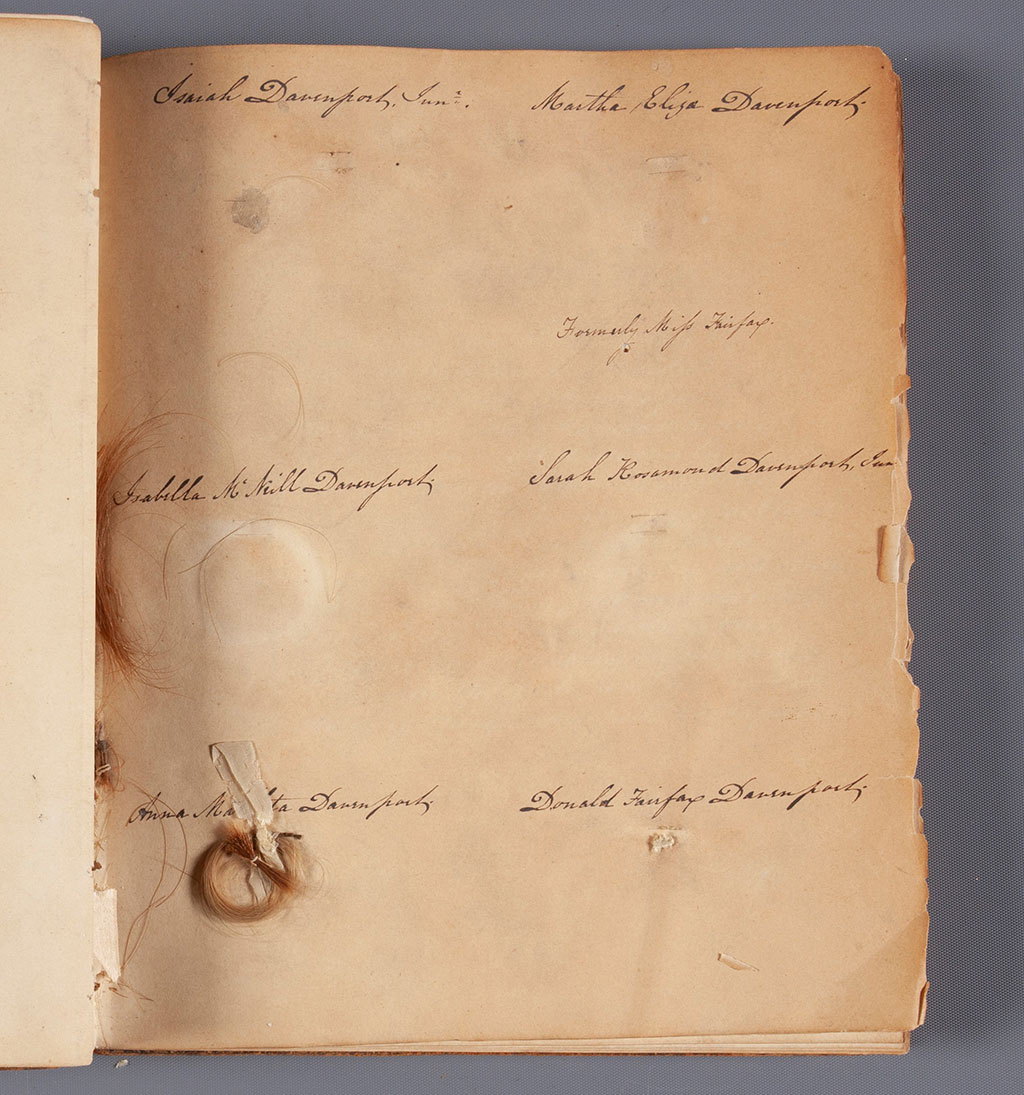

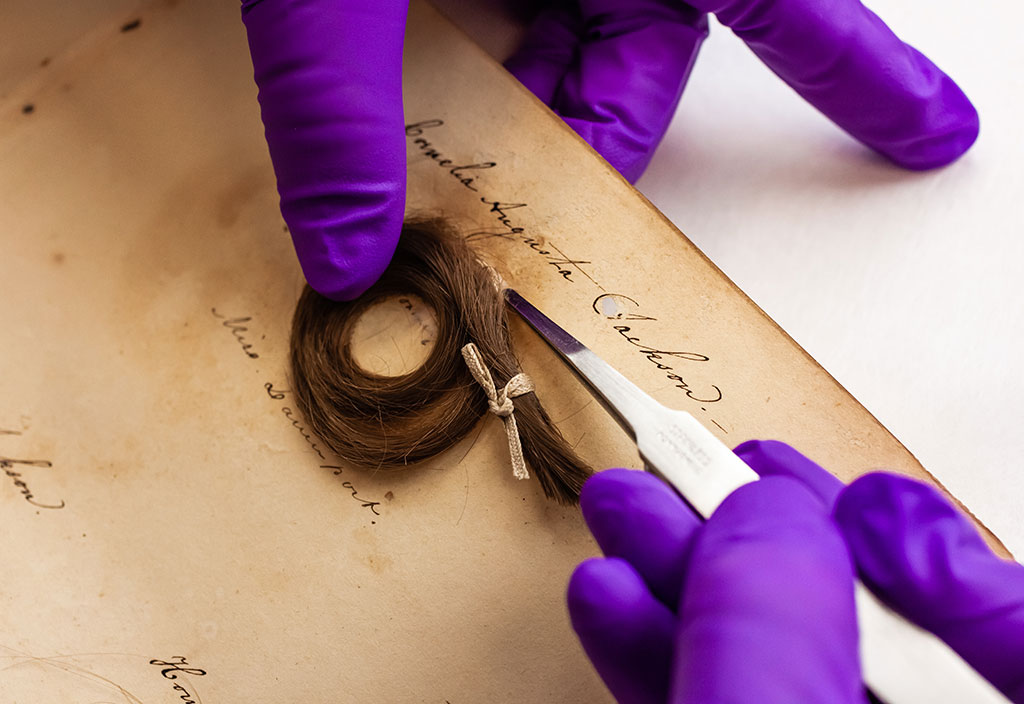

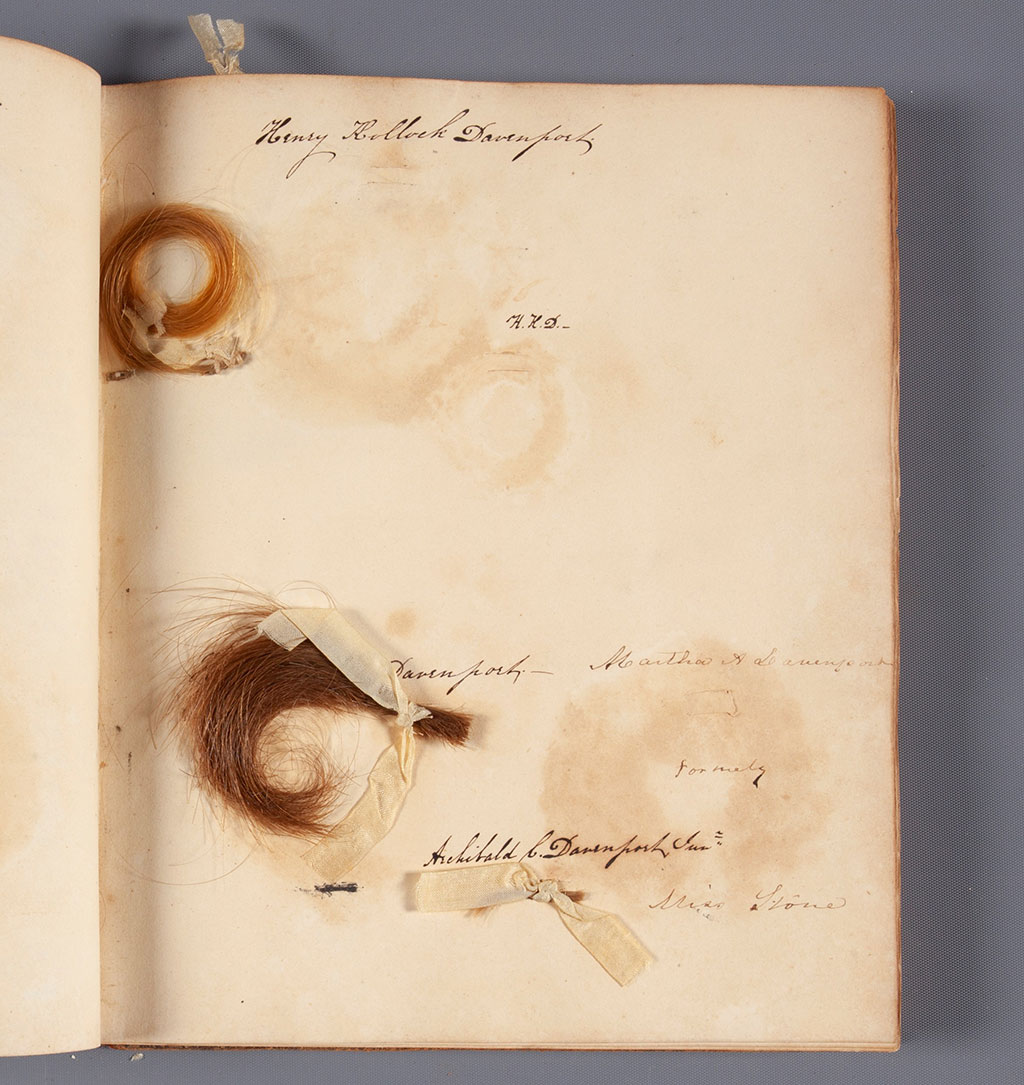

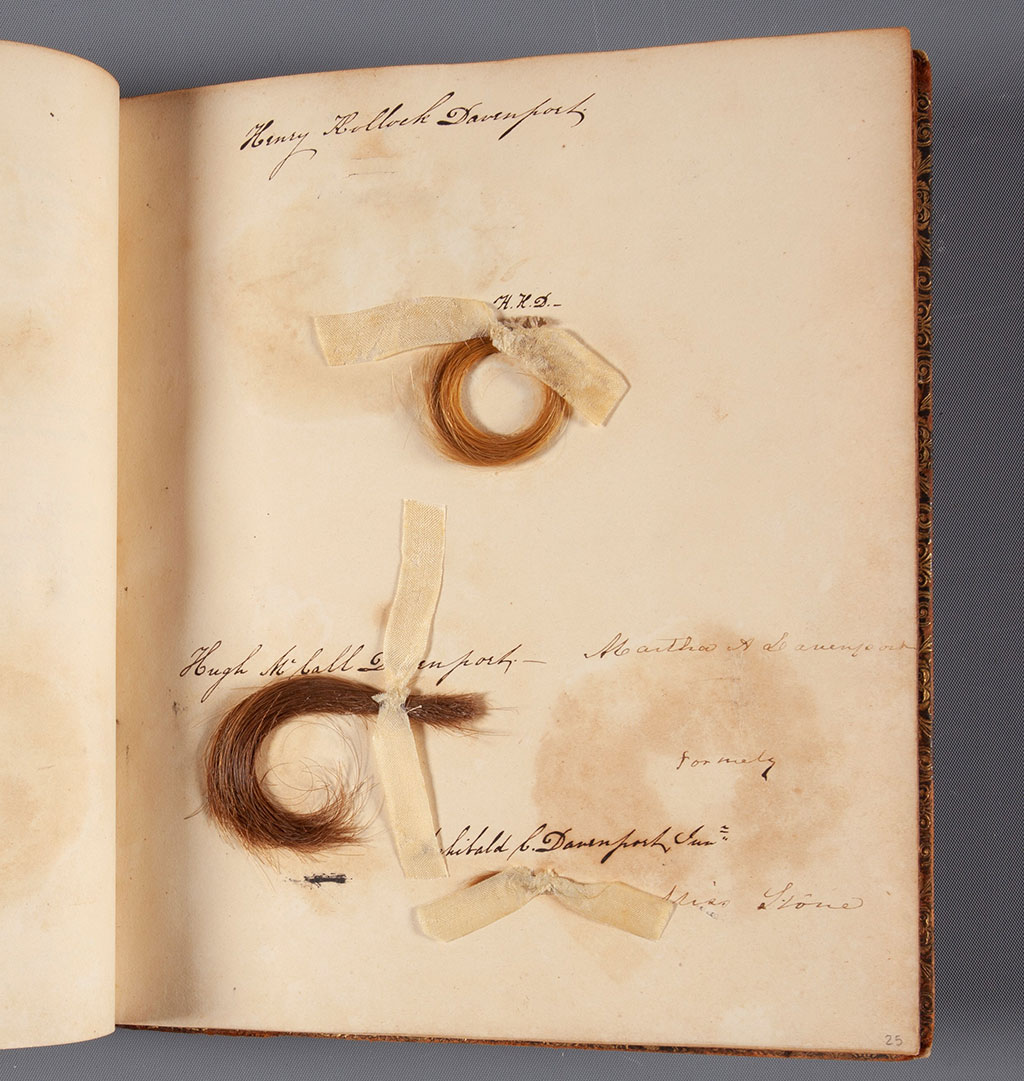

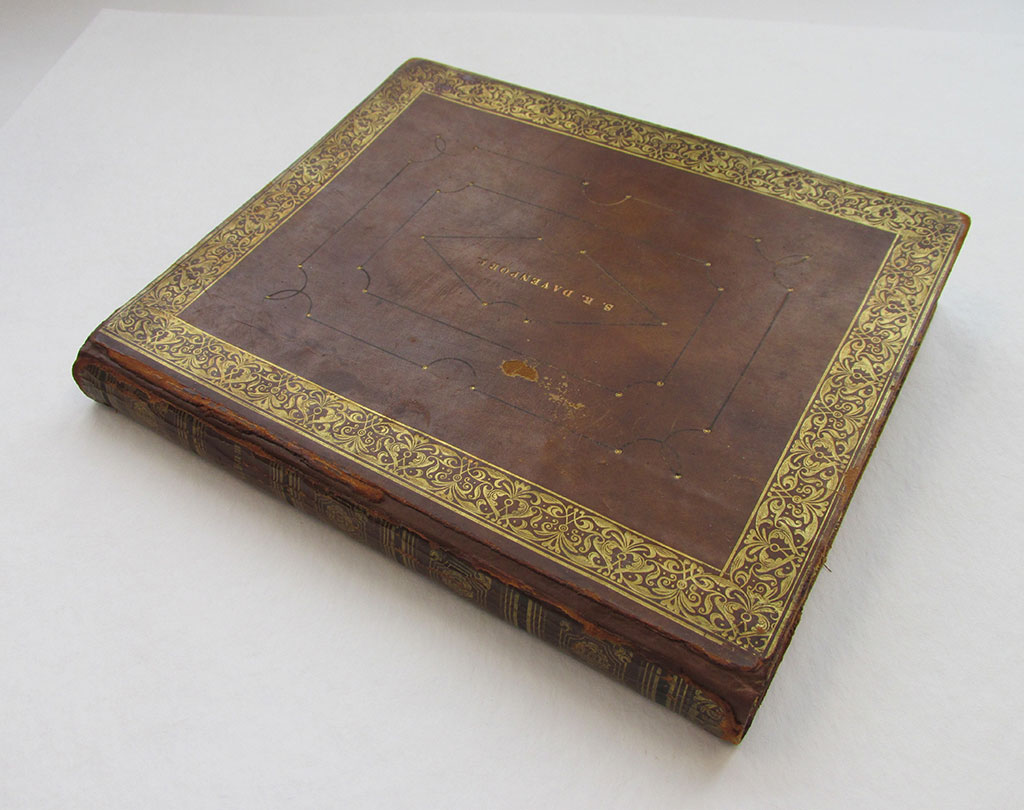

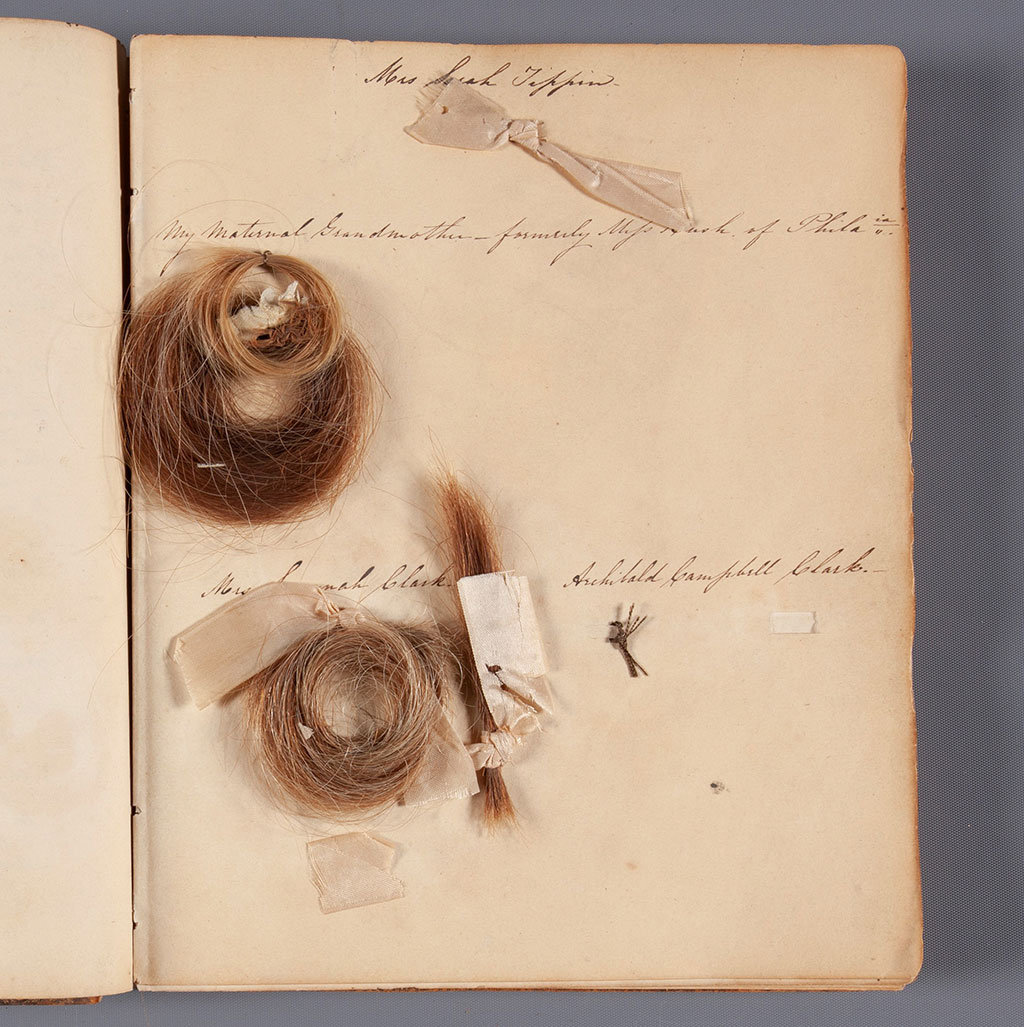

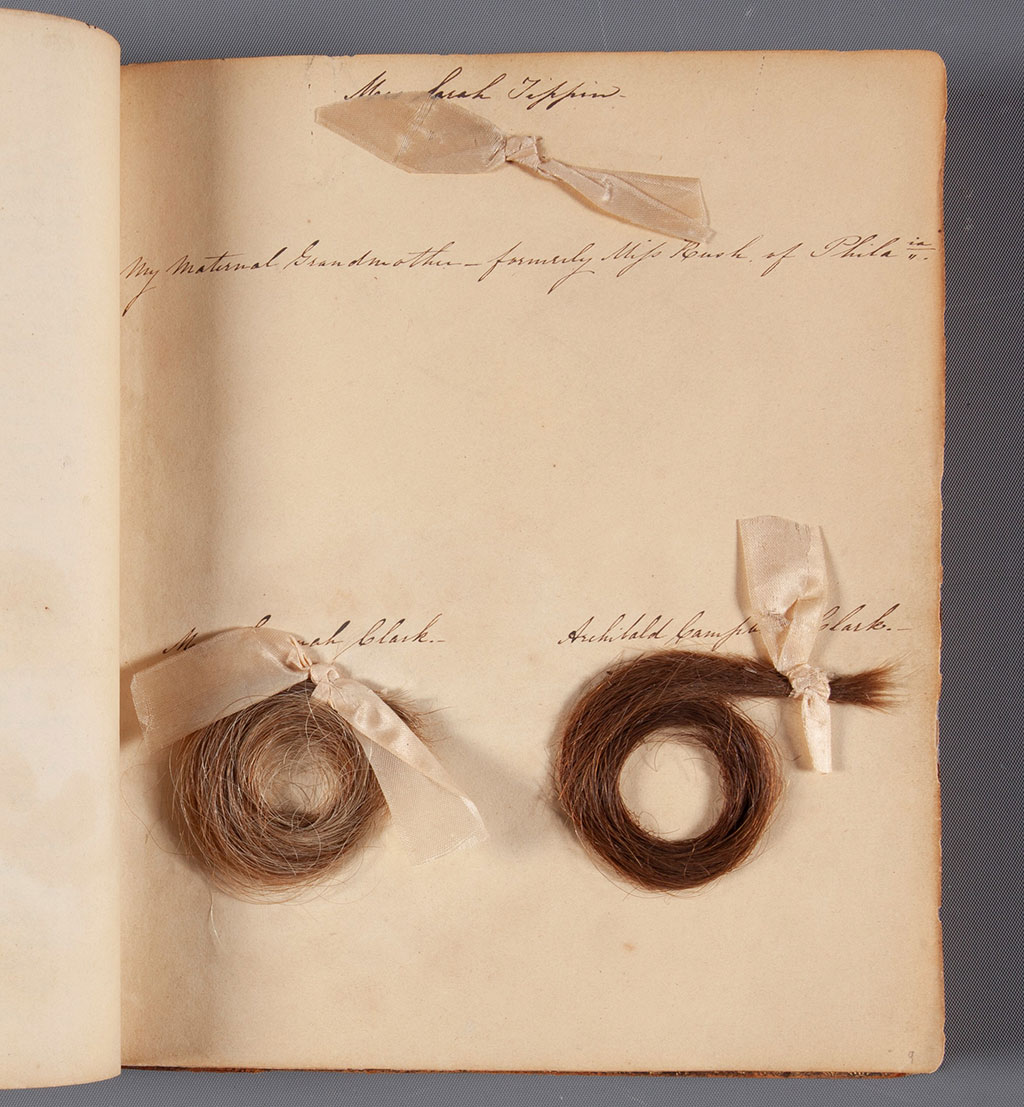

In 2019, the Davenport House Museum in Savannah, Georgia, brought a 19th-century hair album to NEDCC for assessment, conservation, and digitization. This album contained locks of human hair that Sarah had collected from her family and tied to the pages of the text block using silk ribbons. Due to the presence of this hair, which was brittle and often detached from the book, as well as the need to preserve the artefactual value of the volume, this project proved to be an interesting conservation challenge and required drawing upon elements of textile and objects conservation as well as book and paper conservation to find a workable solution.

Because this project was so complex, this story has been split into two parts. For more information on this project, including a full description of the album, background on Victorian hairwork, history of the Davenport family, and the ethical decision-making required by this project, please see Part 1 - History of Victorian Hairwork and Background of the Davenport Album.

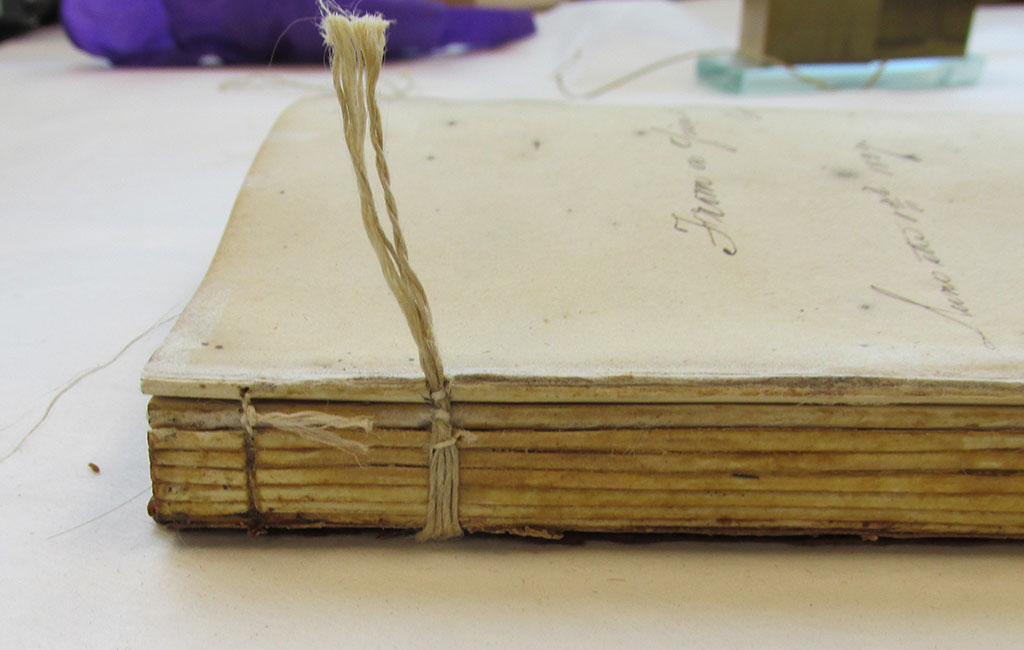

Sarah Davenport's Album Before Treatment

Documentation

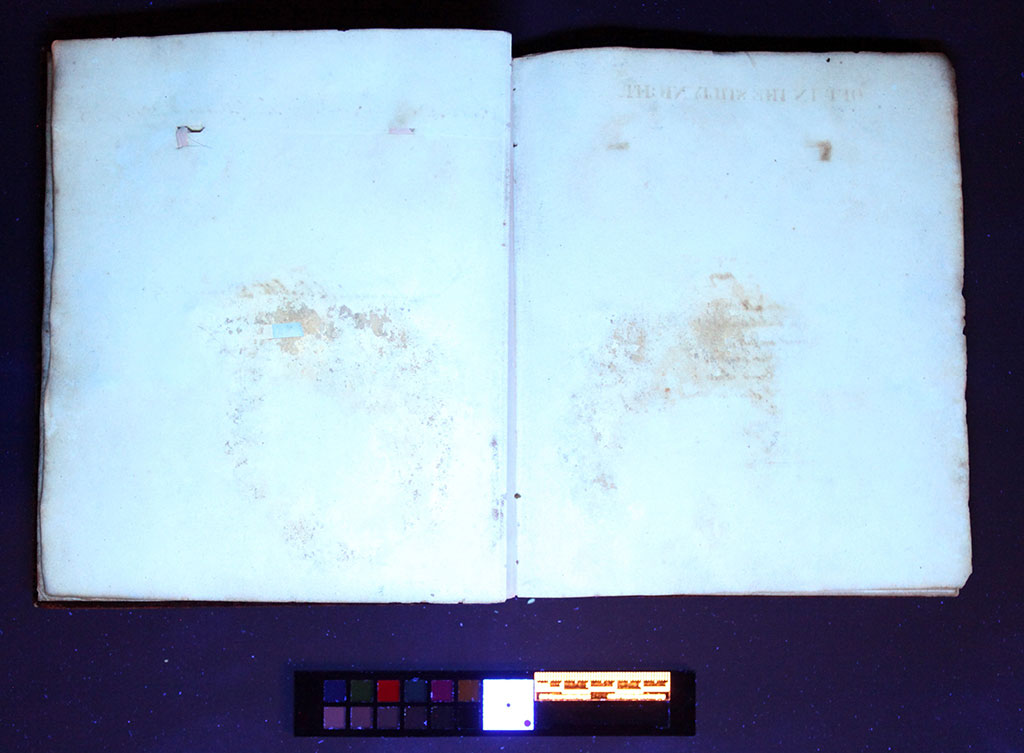

One unexpected difficulty was deciding where to reattach the hair, since some leaves had multiple detached locks, or locks had clearly been placed on support leaves that did not originally contain hair. To avoid a curatorial mistake, absolute confidence in the hair’s correct placement was necessary prior to reattaching the hair. To this end, every single leaf containing hair locks was imaged during the photodocumentation process to record their locations at the time of arrival at NEDCC. UV imaging of these leaves also helped reveal some hidden outlines of discoloration on the support leaves in the shape of hair locks, which was later integral to determining their original locations.

A Toxic Mystery?

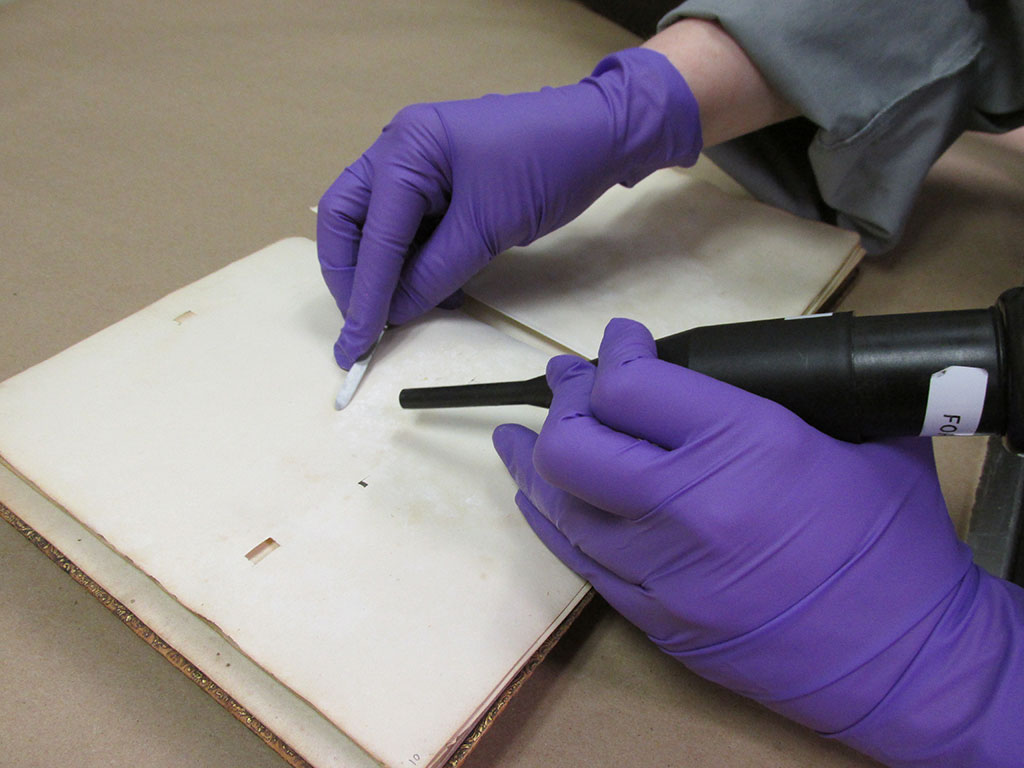

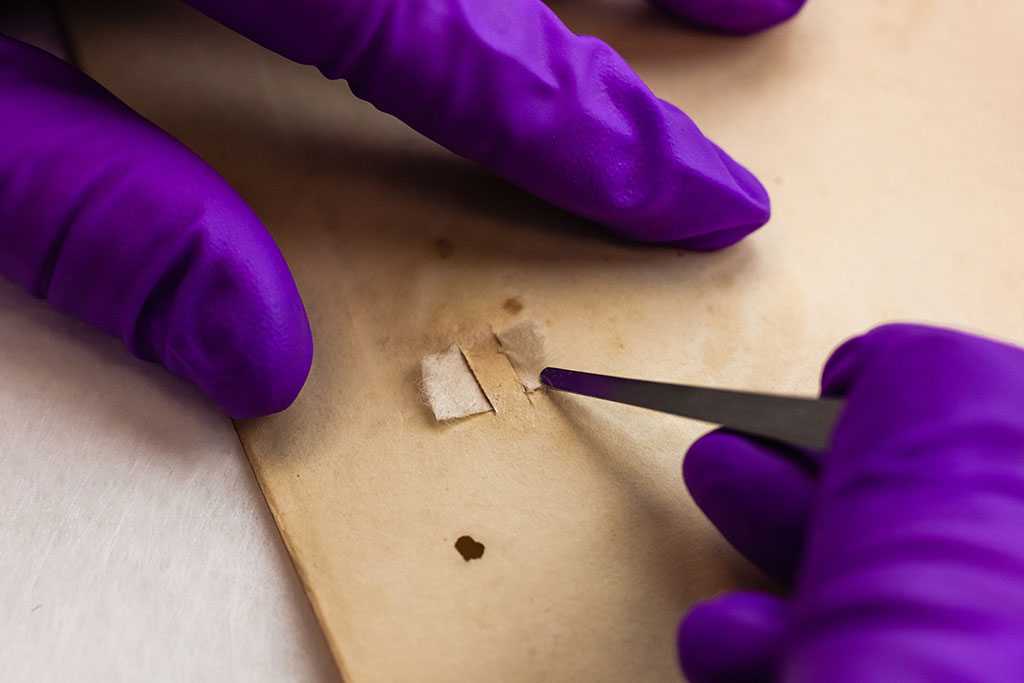

During examination it was discovered that some support leaves contained caked-on white powder. Given the Victorians’ fondness for treating natural history specimens with arsenic, mercury, and lead, NEDCC didn’t want to take the risk of unknowingly exposing its employees to a hazardous material and so the conservator and photographer wore nitrile gloves, an N95 mask, and a lab coat every time they worked with the book.

A mysterious white powder, shown here under UV light, was found on blank support leaves. It is likely that this powder is an insecticide based on the presence of hair in the album.

The mysterious white powder had no apparent artefactual value – it was located only on blank support leaves between the leaves containing hair – and so after curatorial approval the white powder was removed as a safety precaution using a HEPA-filtered vacuum in a fume hood. This reduced the risk of cross-contamination from the volume, but did not eliminate it, so the conservator and photograph continued to wear PPE throughout the remainder of the treatment process.

Removing the white powder using a HEPA-filtered vacuum. The book is not considered fully decontaminated, even after vacuuming and surface cleaning, so the conservator and photographer needed to wear PPE throughout the project.

Disbinding and Text Block Repairs

Lifting leather from the boards in preparation for cleaning the spine and repairing the binding.

After a thorough surface cleaning and vacuuming to remove as much of the potential contaminants as possible, the next step was to partially disbind the volume. The leather on the boards and spine was lifted to facilitate the eventual reback and also to improve access to the spine for cleaning. The spine was cleaned with a 4% methyl cellulose poultice; because the back board and spine leather were still attached to the binding, these areas were masked off with Melinex to avoid damaging the leather. Once the spine was cleaned, the first two sections, which were already loose and almost entirely detached, were removed. The spine folds were guarded and tears and losses in the support leaves were mended with Japanese kozo tissue and wheat starch paste.

Cleaning the spine with a 4% methyl cellulose poultice. The poultice helps deliver moisture to the spine glue in a gentle and controlled manner. Once the glue is softened, it can be removed with a microspatula.

Stabilizing the Hair Locks

The stabilization of the hair locks was the most difficult part of the conservation process and required thinking outside the box. The hair was too brittle to simply reattach by tying ribbons through the slits in the support leaves, and many of the support leaves had torn because of this original attachment method anyway. A thorough literature search was conducted, but there seemed to be no direct precedents available to help guide the project. Two textile conservators, Camille Myers Breeze and Morgan Blei Carbone of Museum Textile Services, were consulted to discuss how they stabilize particularly fragile textiles such as quilts and flags as the hair could loosely be considered a textile. In this approach, fragile materials are stitched between a backing layer of polyester woven textile and an upper layer of nylon thermoset net using an ultrafine polyester thread. As historic wigs are often created by stitching and knotting hair to mesh textiles, it was felt that there was a strong historic precedent for using this approach.

Both hair and woven textiles contain thread-like materials, so it was possible to adapt textile conservation techniques to stabilize the hair.

Refining the Technique

Before attempting to use this method with the historical locks of hair, the technique needed to be adapted and refined using sample models to make sure that it actually worked and that it would be appropriate for the scrapbook. Real human hair is difficult to obtain, so hair silk was used in these experimental models since it looks and feels almost identical to human hair.

During testing, it was discovered that the thermoset net was very visible when laid over the top of the hair and to use it would certainly detract from the appearance of the volume. It was also discovered that the fine woven polyester backing layer (Stabiltex/Tetex) was very prone to fraying, and that it would be necessary to heat seal the edges after trimming it down to size. While it was possible to do this, the heated tool would need to get very close to the historic hair and this was determined to be too risky. The thermoset net, on the other hand, did not fray when trimmed, making it an ideal backing layer and so this was selected instead of the polyester textile.

A loop of hair silk was used in place of actual human hair when experimenting with stabilization techniques.

Nylon can be a controversial choice of textile – there is evidence that it degrades when exposed to light. In this case, the netting would be covered by hair in the closed pages of a book, which would then be stored in a custom drop-spine cloth-covered box. For this reason, light exposure to the volume long-term would be minimal, so it was decided to proceed with the nylon textile since it seemed to offer the most support while minimizing visual impact. The thermoset net comes in sympathetic colors to the various hair shades, and so it was possible to obtain a very close visual match. Likewise, the Gutermann Skala 360 polyester thread recommended by Camille and Morgan was ideal for stitching the hair to this textile – it comes in a variety of colors and is hair-thin, so it blended in very well with the rest of the hair.

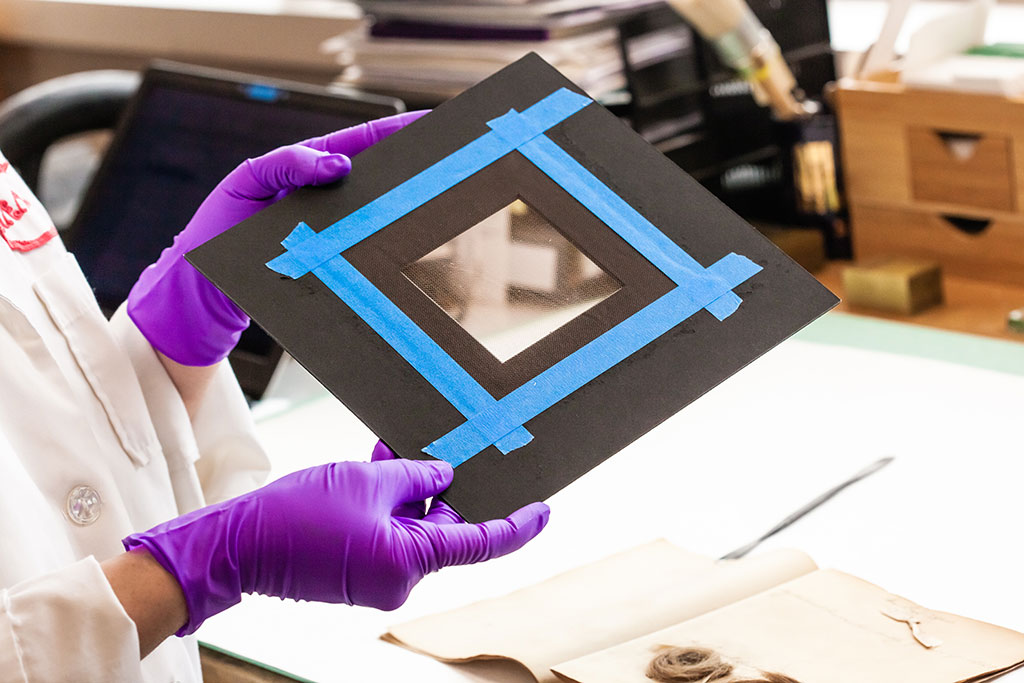

Creating a Sewing Frame

To stitch the hair to the net, the netting needed to be held at an even tension so that the hair wouldn’t pucker or stretch after stitching, but lie flat with minimum stress to the hair. An embroidery hoop would have stretched the net too much, causing uneven tension when released. Instead, a window mat with 3” borders and a 3” square interior window was cut out of a piece of black mat board. A small square of textile was then attached to the mat board using painters’ tape. The tape held the textile flat with only minimal tension so that the textile would not contract when released. The painters’ tape was used to ensure that the tape could be removed relatively easily. As a result, the tape and mat board could be reused over and over again and this reduced waste materials.

Nylon thermoset net was attached to the mat board using painters’ tape. The tape held the net flat without stretching the net.

Attaching the Hair to the Textile

Once the netting was attached, the board was flipped over so that the hair could nestle inside the recess of the window mat. This was done so that when the thread was tied off at the back of the textile there wouldn’t be any additional pressure placed on the hair. Before putting the hair onto the net, a simple square knot was tied around one thread of the nylon net using the polyester thread. The thread tended to slide out of the eye of the needle, so a square knot was tied around the eye as well.

Tying the Gutermann Skala 360 thread to the net textile. The thread was so fine that it closely resembled hair.

The polyester thread color was chosen based on the hair’s hue and most of the locks were a good match to the dark brown, medium brown, or light yellow threads. After the hair was laid upon the backing textile, it was gently arranged so that the curl of the lock fell in the most natural position. Any strands of hair sticking out from the lock were tucked back in so that they would be included in the stitching process.

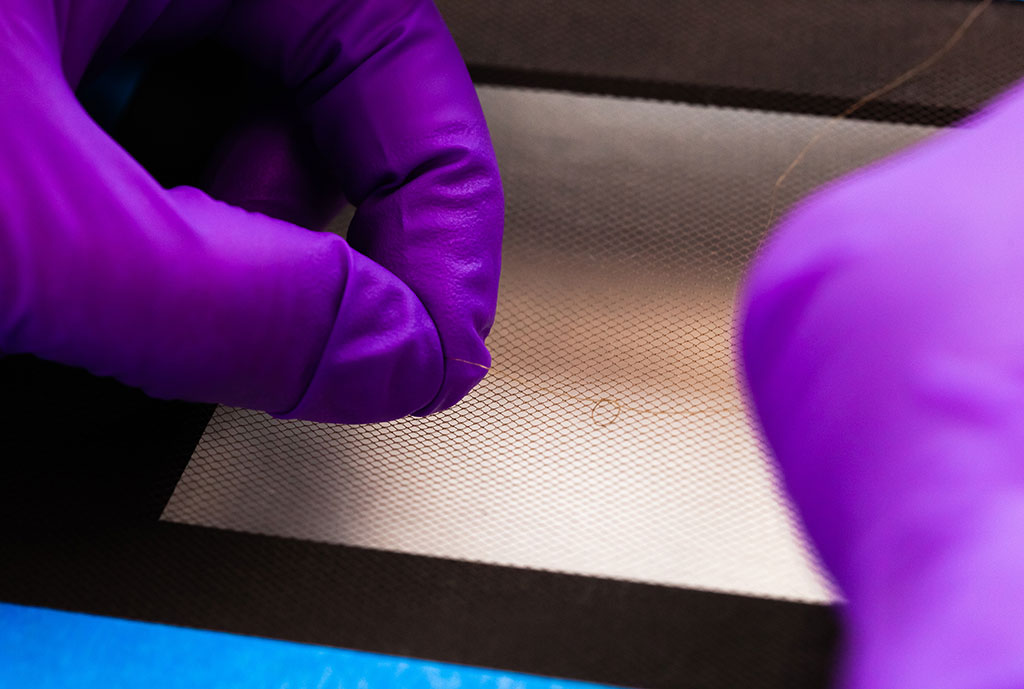

Arranging the hair on the net textile.

Compression points were avoided during the stitching process because they could cause the hair to break over time. Stress on the hair was minimized by keeping the tension of the thread loose and also by sewing with long stitches to spread any strain over a larger surface area. The technique that seemed to work best was to thread the stitch through several layers of hair at varying depths. This method held the hair in place, but also meant that very little of the stitch was visible from the surface. Once sewing was complete, the thread was tied off from the back of the textile and threaded through the nylon net before trimming the thread ends.

The thread was woven through several layers of hair at varying depths. To avoid strain on the hair, the stitches were kept long and loose.

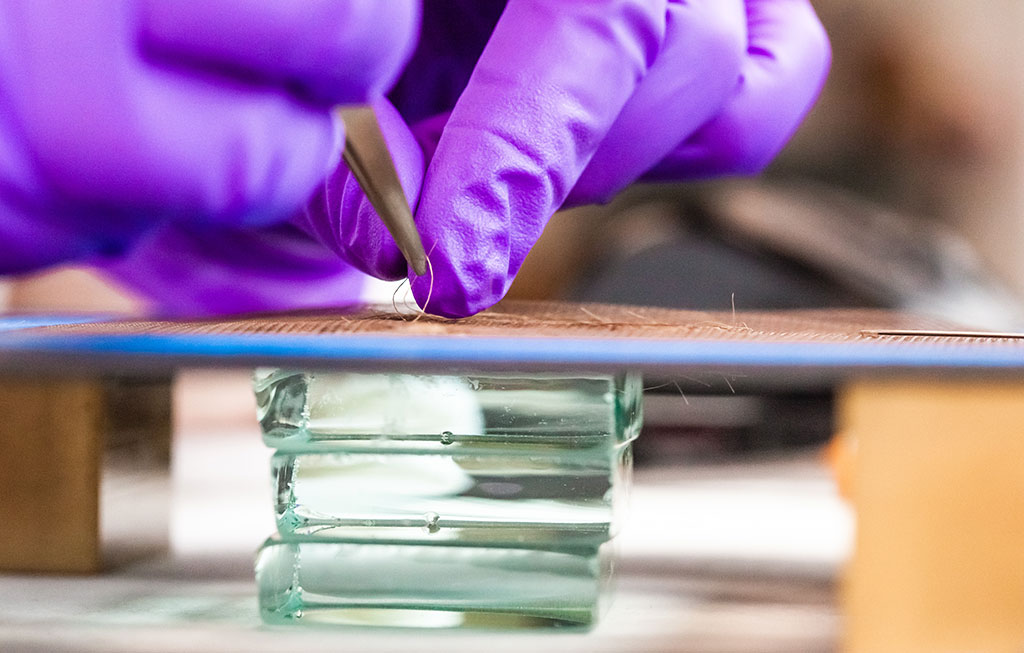

Once sewing was complete, the thread was knotted off in the back and woven into the textile. Glass blocks were used to support the hair during this process.

The net was then trimmed as closely as possible to the hair. Where necessary, the hair was held gently by a microspatula or flat-edge tweezers when trimming to avoid an accidental haircut. The inner circle of a hair lock was trimmed first followed by the outer edge of the lock. It was important to trim the net in this order because it was easier to maintain net tension and avoid hair movement if the outer net was kept intact while the inner circle was cut.

Trimming the net textile using a scalpel. Tweezers were used to hold the hair away from the sharp blade.

After sewing and trimming, the net and thread were almost invisible underneath the hair when viewed from the top down. When looking at the back of the lock of hair, the textile and thread were quite a bit more distracting, but luckily the locks of hair would not be viewed in this manner after remounting.

A hair lock after stabilization. The thread and backing textile are almost invisible.

The stabilized lock of hair as viewed from the back: the backing textile and thread are much more visible here.

UV Imaging and Determining Original Lock Locations

UV imaging helped reveal further staining from the hair on the support leaves, and was very useful for determining hair lock locations when discoloration was not obvious under natural light. UV imaging also conclusively proved that locks of hair had gone missing from the album at some point in time. The album contained a number of names with no associated hair or immediately apparent staining. There were slits in the paper underneath the names, clearly made in preparation for mounting the hair, but seemingly no definitive evidence that the hair had ever actually been there. Under UV light, many of these apparently blank support leaves suddenly showed visible areas of discoloration where hair locks had previously been attached. Although the locks are now missing, this tells us that the hair was lost after they’d been attached for a long enough period of time to leave discoloration on the paper.

UV imaging helped reveal staining in the support leaves.

Remounting the Hair to the Support Leaves

The hair was reattached to the support leaves using slips of Japanese kozo paper lightly toned with acrylic pigments to be a better color match to the support leaf. The paper slip was attached to the nylon thermoset net by sewing a small strip of additional net over the paper to the hair’s support netting. Several stitches went through the paper slip to help secure it.

Sewing the attachment slip to the net textile.

Once stitched, the edges of the paper slip were woven into the preexisting slits of paper in the support leaves and adhered to the support leaf with wheat starch paste. The edges of the slits had previously been reinforced with Japanese kozo paper bridges. The paper slips ends were adhered above and below the slit in the support leaf to avoid placing more strain on the fragile slit. This attachment system means that strain is placed on the nylon net and the slip instead of on the hair or support leaves.

Threading the ends of the attachment slip through slits in the support leaf.

Once the attachment slip was threaded through the support leaf, the ends were adhered above and below the slit using wheat starch paste.

While all of the large locks of hair were able to be reattached to the support leaves, a number of loose hair knots, hair strands, stubs of hair tied with thread, and shreds of degraded silk ribbon were found in the gutter between pages 9 and 17. Because it was unclear which fragments had come from which lock, they were not reattached. To keep the loose hair stubs and knots safe without remounting them, they were stabilized by stitching onto thermoset net. All loose pieces and silk ribbon fragments were stored in labelled glassine bags and returned to the Davenport House Museum.

Stabilizing the Silk Ribbons

The degrading silk ribbons were stabilized where possible using a solvent-set silk crepeline repair medium with Plextol B500 adhesive. The silk crepeline was placed on silicone release Mylar, then brushed with a 3:1 Plextol B500:filtered water solution and allowed to dry. This was tacked in place with low heat from a tacking iron and then reactivated with ethanol to improve adhesion and reduce shine from the adhesive.

The silk ribbons prior to stabilization.

The silk ribbons after stabilization.

Digitization

After the hair and ribbons were stabilized and returned to their originating leaves, but prior to repairing the binding, the volume was digitized in NEDCC’s Imaging Services lab. Imaging at this stage of the treatment captured the volume in a near-complete visual state, but without putting undue stress on the binding. After consulting with the project’s conservator, the volume was captured by one of NEDCC’s collections photographers on a copy stand, manually supported throughout the imaging process. Foam book wedges and microspatulas were used to ensure the volume was stable, pages flat and parallel to the camera, and that all content, including text obscured by the re-mounted hair and ribbons, was fully accessible in the digital files.

NEDCC chose to digitize the volume at an optical resolution of 600 pixels per inch (ppi). While we often image manuscript materials at the FADGI recommended 400 ppi resolution, the decision to use a higher resolution was made to ensure that the fine details of the hair and silk ribbons would be fully resolved in the digital images. When viewing the image files at 100% magnification, the value of these additional pixels can be fully appreciated.

The visually accurate, high resolution images will serve an important role in the long-term preservation of the album, even in its stabilized state, by allowing the Museum to offer primary research access via the digital surrogates. Digital access is particularly vital for a volume with complex, fragile enclosures like Sarah’s album, as it reduces mechanical stress from handling on both the hair and silk ribbons themselves and on the album pages onto which they’re mounted. The digitized album can now be viewed on the Davenport House Museum website, allowing worldwide access to this unique book.

Binding Repairs

After the hair had been remounted, the sewing of the text block was reinforced by stitching over new sewing supports which also served as board attachments. Additional space was given between the resewn sections to accommodate the bulk of the hair so that the text block was no longer compressed or wedge-shaped. The new cord sewing supports were frayed out so that their mass would be diffused over a large area and be less noticeable once the leather was readhered. The sewing supports were pasted onto the boards and then the album was rebacked with toned Japanese paper and airplane cotton.

The sewing was reinforced over new sewing supports.

The sewing supports were frayed out and pasted to the boards to form new board attachments.

The book was rebacked using toned Japanese paper and airplane cotton.

Conclusion

This new treatment approach successfully balanced competing curatorial and conservation priorities by stabilizing and remounting the hair locks into the album without causing harm to the hair or the support leaves. The most minimally interventive approach of rehousing the loose hair and storing it separately would have stripped the album of its artistic and historical significance, and perhaps could have caused even more damage to the hair in the long run due to an increased need to handle the unbound locks.

Sarah Davenport’s album before conservation.

Sarah Davenport’s album after conservation.

Stitching the hair onto the net textile meant that individual hairs were less prone to breakage from mechanical wear since the nylon thermoset net and thread helped protect the hair from excess movement. Any stress sustained by pressure from the sewing thread on the hair was minimized by sewing loosely with relatively broad stitches, and by the large number of stitches. The sewing threads form an internal network of support, keeping the hair stable and secure without undue restriction.

Remounting the hair locks into the album will help prevent the hair from being lost in the future – an important priority since so many locks had already gone missing over the course of the last 191 years. The remounting method ensures that the nylon thermoset net and not the hair will take the strain of attachment. Additionally, by securing the Japanese paper slips to the support leaf above and below the slits in the support leaves, rather than around the slits themselves, the support leaves are less likely to tear from mechanical wear during use. Resewing the text block to include extra space between the bulkiest sections helped reduce stress along the spine and front joint, leading to greater long-term stability in the binding.

Reconciling the treatment needs of the hair locks with the curatorial need to maintain the album’s historical and artistic integrity was challenging, but not impossible. The decision-making process required thinking outside the box, consulting with conservation experts outside of the book and paper field, extensive research into historic human hair, and a full consideration of the practical and ethical aspects of all potential treatment options.

The treatments performed on the hair, text block, and binding restored functionality to the album and ensure that a modern-day visitor to the Davenport House Museum will have a very similar visual reading experience to Sarah Davenport herself.

LEARN MORE

About the Davenport House Museum, Circa 1820, Savannah, Georgia

Throughout its 50+ years as a historic site, the Davenport House Museum has treated visitors to intriguing and vivid experiences centered on a legendary Savannah-centric tale of courage and determination. Visit: www.davenporthousemuseum.org

The digitized album can now be viewed on the Davenport House Museum website, allowing worldwide access to this unique book.

WATCH THE VIDEO: Associate Book Conservator Mary Hamilton French speaks about the Sarah Davenport album for the Old Stone House Museum & Historic Village.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Bexx Caswell-Olson, NEDCC Director of Book Conservation for her encouragement to develop this project into a presentation and paper; Annajean Hamel, NEDCC Lead Preparator, for helping make a sewing frame for the hair; Graham Patten, a Book Conservator at the Boston Athenaeum, for his helpful advice; and Camille Myers Breeze, Director & Chief Conservator and Morgan Carbone, Associate Conservator, Museum Textile Services for their helpful advice and for generously supplying NEDCC with textiles and thread.

Special thanks to Jeff Freeman, Davenport House Museum Assistant Director and Collections Manager, and the other Museum staff for their enthusiastic permission in letting NEDCC present this conservation project.

Story by Mary Hamilton French, Associate Book Conservator