Part 1: De-Installation and Conservation

In January 2019, a team of three conservators and one collections photographer from NEDCC arrived at Jekyll Island off the coast of southern Georgia to begin a multi-phase project to preserve a Chinese export wallpaper installed on the ceiling of one of the island’s historic homes. The project would encompass three phases: first, removal and rehousing of a bamboo framework and wallpaper panels, both installed on the ceiling, on-site; second, treatment of a single wallpaper panel at NEDCC; and third, digital imaging, digital restoration, and printing reproductions of the wallpaper for installation in place of the originals.

Part 1 of the story details the history of the Island, the decision-making process leading up to the wallpaper project, and the work required to de-install and conserve the wallpaper. Part 2 of this story details the digital imaging, restoration, and print reproduction process.

While wallpaper treatments are notoriously difficult for a number of reasons, this project had additional challenges that required the conservators and imaging staff to be creative and adaptive in their approach.

History of the Jekyll Island Club

The Jekyll Island Club was a winter retreat established in 1886 by some of the world's wealthiest people, most notably the Morgans, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts. While reaching the island in the late 1880s was hard enough, to further preserve the club’s exclusivity membership was restricted to 100 members. The Jekyll Island Clubhouse, with its signature four-story turret, was completed in January 1888 and became the centerpiece of the grounds, as well as a place of nightly community gatherings for decades.

Jekyll Island, Georgia. Photo Courtesy of Jekyll Island Authority

Jekyll Island was a playground for the club members’ families to relax and enjoy activities such as biking, hunting, horseback riding, and tennis. Members could also retreat into nature and enjoy the scenic views from the island.

Curiously, in November 1910 it was also the location for the strangest and most secret expedition in the history of American finance. Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich, chairman of the National Monetary Commission at the time, summoned together the country's leading financiers, who together represented about one sixth of the world's wealth. The pretext for the gathering of these powerful figures was a duck hunting trip on Jekyll Island. Instead, they met to discuss monetary policy and the banking system. From these secret deliberations emerged the present Federal Reserve System.

Another historic event took place on Jekyll Island in January 1915 when the first public transcontinental telephone calls were placed from Jekyll Island. American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) president and Jekyll Island Club member Theodore Vail called President Woodrow Wilson in Washington, Alexander Graham Bell in New York, and Thomas Watson (Bell’s assistant) in San Francisco.

The Jekyll Island Club’s retreats ended in 1942 when the United States entered World War II and the island was evacuated for security purposes. In 1947, the State of Georgia bought the island for use as a state park. Since 1950, the Jekyll Island State Park Authority has operated the island for the enjoyment of guests, while conserving the natural resources of the island, and preserving its historic resources.

Towards this end, Jekyll Island Museum was founded in 1954 as the steward of the Island's past. The Museum’s mission is to protect all of the cultural resources of Jekyll Island and to preserve them to the highest standards possible, allowing for an engaging and enriching experience for the citizens of Georgia and beyond. The Jekyll Island Museum manages a collection of approximately 3,000 historic books and reference materials, 5,000 archival documents, 10,000 artifacts, and 20,000 images. Today, thirty-four buildings erected during the Jekyll Island Club era remain part of the designated 240-acre Historic District and under the care of the Museum.

Mistletoe Cottage

Mistletoe Cottage

Photo Courtesy of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum, of the Jekyll Island Authority

The Chinese Wallpaper of Mistletoe Cottage

Mistletoe Cottage was commissioned in 1900 by locomotive manufacturer Henry Kirke Porter from architect Charles A. Gifford. It is one of the most visited and carefully preserved mansions of the Jekyll Island Historic District, though it was affected by modernization efforts that occurred on the island during the 1950-70s. The cottage included a conservatory, located on the ground floor at the southeast side of the house, with two walls of large window panels looking out onto the surrounding patio and gardens. The room once featured a highly decorative and visually complex Chinese export wallpaper, a common element of interior décor in the homes of America’s wealthy during the turn-of-the-century. While some of that original wallpaper remained installed in the conservatory, it required the attention of paper conservators and a strategy for its reinstallation.

The Chinese export wallpaper covered the entire ceiling of the conservatory.

The wallpaper was adorned by a latticework of shellacked bamboo rods nailed in place over the paper,

creating the illusion of an airy pergola.

Onsite Condition Assessment to Create a Treatment Plan

The wallpaper in question covered the entire ceiling of the conservatory and was adorned by a latticework of shellacked bamboo rods nailed in place over the paper, creating the illusion of an airy pergola. Local archival records indicate that the walls were once decorated with the same wallpaper but that it had been removed during a previous renovation or restoration effort.

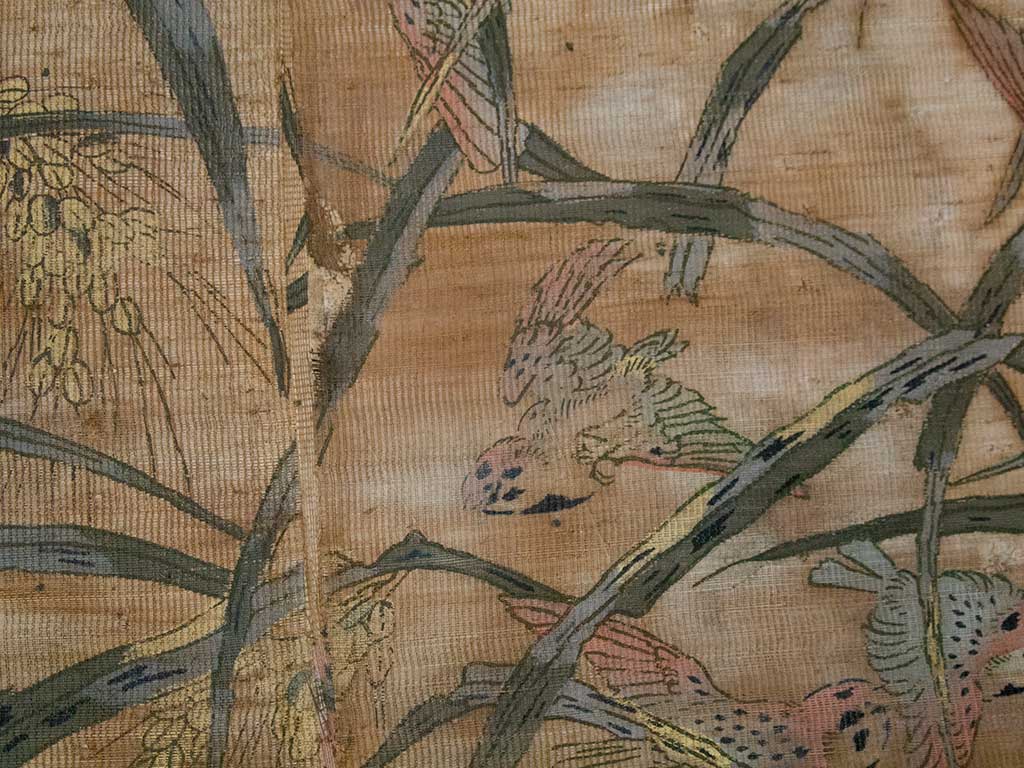

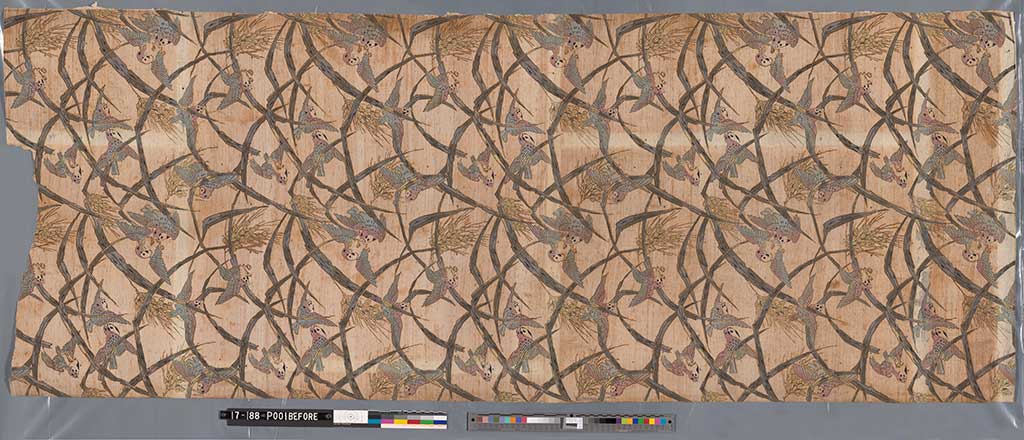

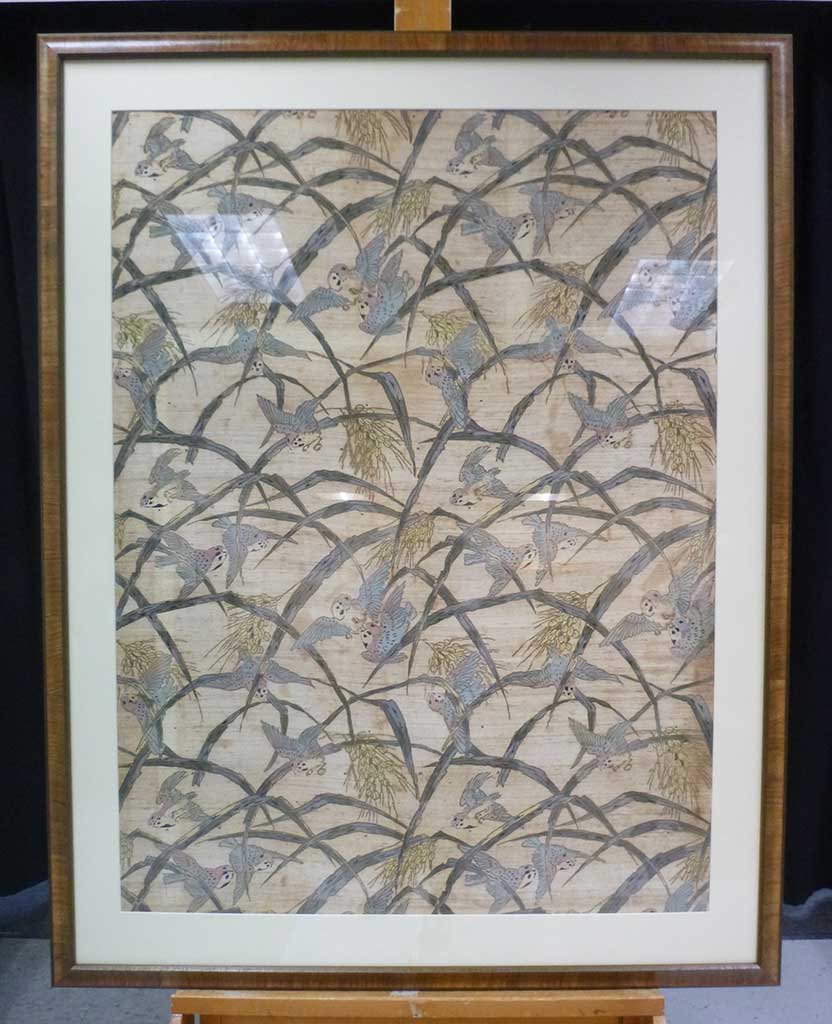

Detail of the wallpaper's motif of leaves and birds

The wallpaper design displayed a motif of repeating green leaves and rice panicles surrounded by fluttering pairs of colorful birds.These 34 ¾-inch wide panels were block printed onto a very lightweight open weave cotton gauze fabric backed with paper. The underlying paper support consisted of two layers of thin Chinese paper adhered together. The first layer was white in color and had strong foxing, while the second paper layer’s verso had yellowed to an ochre color, giving the wallpaper an off-cream appearance overall. The wallpaper had darkened irregularly due to continued exposure to UV light, uncontrolled fluctuations of temperature and humidity, and damage from water intrusion and other conditon issues. The first two disfigurements were primarily caused by the continuous exposure to sunlight through the two full walls of windows.

The wallpaper’s media also exhibited damage from the uncontrolled light exposure. The pigments had oxidized and discolored from their original tonal intensities. Furthermore, some of the pigments had lost adhesion and were flaking locally especially in the ochres, reds, and light blues. Given the conservator’s experience with 19th century Chinese wallpaper and the materials used in its printing, there was concern that some of the media might contain components dangerous to human health. Samples of flaking media were collected and tested confirming the presence of copper, iron, lead, and arsenic. These hazardous components would complicate any efforts at de-installing the wallpaper, necessitating the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and making a difficult task even more challenging.

The wallpaper's media exhibited damage from light exposure.

Time and environmental conditions had caused large swaths of the wallpaper to loosen or completely detach from the ceiling, while more protected areas, such as those under the bamboo latticework, remained firmly attached. In addition to the underlying failing adhesive, there were also many areas where the fabric gauze had detached from its paper support. Multiple tears were noted at the time of assessment and these were later found to correspond with cracks in the underlying ceiling plaster.

Damage from mold, mildew, and previous attempts to re-adhere wallpaper

A large area of extensive dark brown staining that affected nearly one-third of the wallpaper was present along the southeast wall. Based on conversations with Museum staff, this staining was traced to a leak from a defective air conditioner in the room above. Upon closer inspection, black mold was discovered underneath the loosened paper. More localized traces of mildew and mold were noted on the surface of the wallpaper near the room’s chimney, possibly due to condensation and airflow issues. Small areas of dark reddish-brown stains were also present and were believed to be caused by previous attempts to re-adhere the paper or gauze with a glue that had since discolored. Surface dirt, insect deposits, cobwebs, and other accretions were found across the entirety of the ceiling.

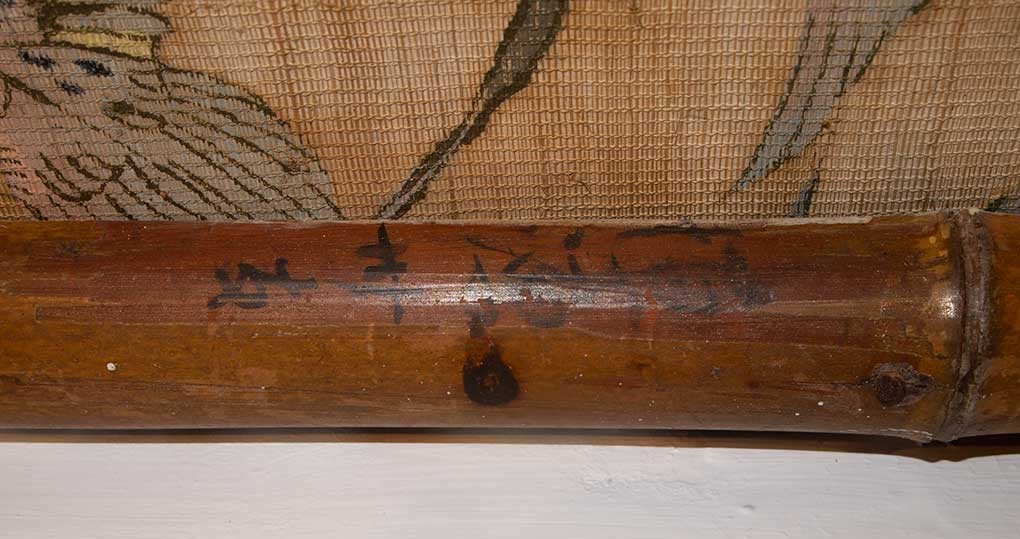

The bamboo trellis of joined half-round bamboo rods added further decorative impact to the wallpaper. The bamboo rods were varnished with shellac and nailed into the ceiling with long, heavy-duty carpentry nails.

The shellac had darkened due to exposure to light, as well as natural aging. The bamboo also had traces of insect damage though this was more clearly visible on the interior. Several of the rods were splintered and cracked. Based on available evidence, the splitting was caused by a combination of mechanical damage incurred during previous attempts at removing the rods and by changes in humidity and temperature that had caused the bamboo to expand and contract rapidly.

The shellac had darkened due to exposure to light, as well as natural aging.

Treatment Planning

Considering the design of the room with its inherent vice of continued unprotected exposure from the east and south window walls, and due to the extensive and disfiguring damage to the original wallpaper, NEDCC recommended having the wallpaper panels removed, housed in archival enclosures, placed in storage, and then replaced with reproductions.

Based on the above assessment and in consultation with the Museum’s staff, the goals of the eventual project were to preserve as much of the wallpaper as was reasonable and to create a reproduction of the wallpaper that could be installed by local professionals. This would then allow for the re-installation of the original bamboo framework on top of the reproductions. One advantage of creating and installing reproduction wallpaper, beyond keeping the original wallpaper safe from the negative impacts of long-term display, would be the option to re-wallpaper the entire room as it was originally envisioned based on the archival evidence.

To achieve the identified goals, NEDCC proposed to de-install all of the wallpaper from the conservatory’s ceiling, select a panel in the best overall condition from the de-installed paper, and send the selected panel to NEDCC’s lab in Andover. Once at NEDCC, a conservation treatment plan would be developed and executed after a more comprehensive assessment. The panel would then be digitized so that the image could serve as the foundation of reproduction wallpaper before finally being framed to allow for display in the cottage alongside the installed reproduction as part of the Island’s interpretive program. With the high-resolution digital image of the conserved wallpaper reproductions could then be generated, as will be discussed in Part 2 of this story.

PHASE 1: In-situ Treatment at Mistletoe Cottage

The removal of the wallpaper from the ceiling was a multi-stage process that took several days to complete. Due to the safety concerns surrounding the media, as well as the presence of mold, water damage, and insect activity, NEDCC staff took precautions by wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) while working onsite. The PPE included N95 masks, nitrile gloves, goggles, and Tyvek coveralls. Furthermore, because the wallpaper was on the ceiling, staff worked on scaffolding and navigated tight angles during the removal.

Bamboo Lattice Removal

Treatment began by removing the bamboo latticework in sections. The bamboo lattice was mapped prior to being de-installed from the wallpapered ceiling so that it could be accurately reinstalled by Jekyll Island staff during the later stages of the project. Each rod was then removed and identified with a tag that corresponded to its position on the ceiling and its NEDCC-generated map. Two conservators worked on each scaffold to remove the bamboo rods by inserting Teflon spatulas between the half-round and the wallpaper to loosen and dislodge the bamboo. If necessary, pliers were used to remove the nails.

Treatment began by removing the bamboo latticework in sections.

The bamboo lattice was mapped prior to being de-installed from the wallpapered ceiling so that it could be accurately reinstalled by Jekyll Island staff during the later stages of the project.

However, in some cases removing the nails cleanly from the bamboo proved very difficult. The extremely long nails had corroded over time and had become embedded in the ceiling plaster. As there was not a distinct head to the nails, it was sometimes easier to slide the bamboo off of the nails and leave them in place for later removal as seen in the photos below. This was especially true when dealing with the cracked, splintered, and insect-damaged bamboo, as it avoided additional stress on the fragile half-rounds.

The extremely long nails had corroded over time and had become embedded in the ceiling plaster.

The extremely long nails had corroded over time and had become embedded in the ceiling plaster.

Removing the remaining nails.

Once removed and tagged, the bamboo was documented, examined, and grouped together based on the map created prior to unmounting. Each piece of bamboo was then surface cleaned with brushes and cotton rags. If the bamboo had a split or was weakened by insect damage, necessary repairs were performed with fish glue, then wrapped in place with safe-release tape to hold the sections together until the glue dried. Each section’s bamboo was then bundled together and wrapped for protection until they could be re-installed with the reproduction wallpaper.

Once removed and tagged, the bamboo was documented, examined, and grouped together based on the map created prior to unmounting.

Each section’s bamboo was then bundled together and wrapped for protection until they could be re-installed with the reproduction wallpaper.

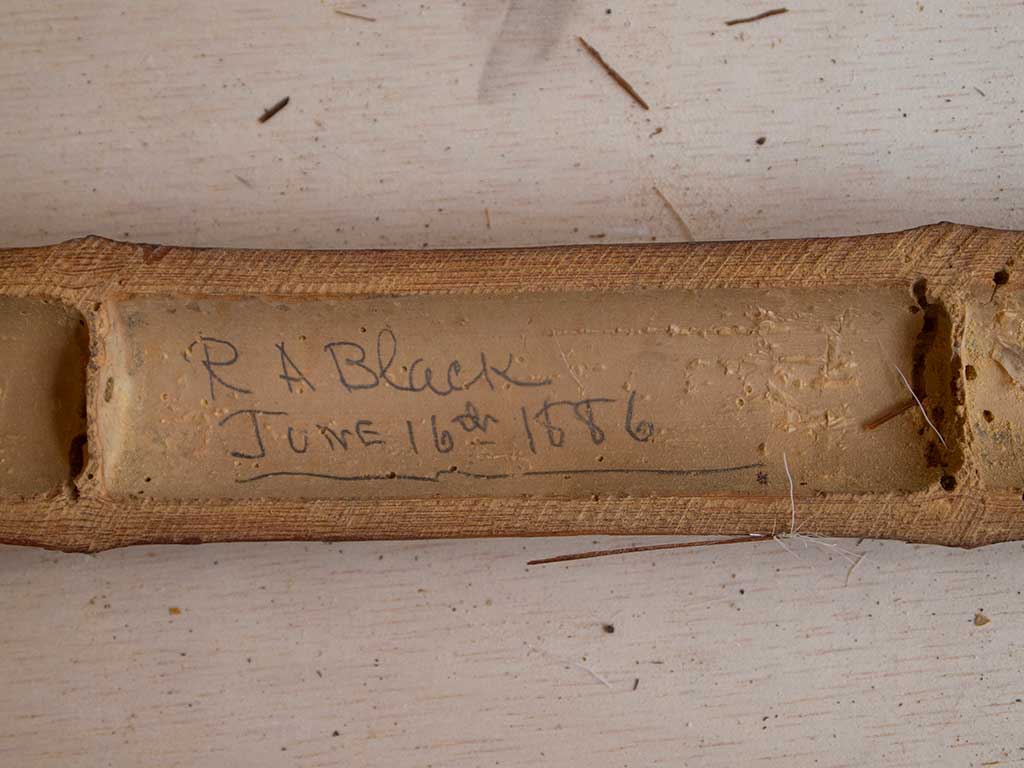

Manuscript writing and signatures in graphite on the inside of the bamboo rods were found and documented.

Wallpaper Removal

Once the bamboo latticework was completely de-installed, removal of the actual wallpaper could begin. At this time the conservators and the collections photographer assessed and further documented the ceiling, determining which panels would both respond best to treatment and provide the best foundation for the reproduction.

The conservators suspected that there might be some difficulty removing the wallpaper due to its irregular attachment, so a removal strategy was tested on a small section of wallpaper near a detached area. This test, using a combination of spatulas and a scalpel to mechanically separate the wallpaper from the ceiling, cutting through adhesive while preventing damage to the ceiling and the wallpaper itself, proved largely successful.

Using a combination of spatulas and a scalpel to mechanically separate the wallpaper from the ceiling, cutting through adhesive while preventing damage to the ceiling and the wallpaper itself.

Using a combination of spatulas and a scalpel to mechanically separate the wallpaper from the ceiling, cutting through adhesive while preventing damage to the ceiling and the wallpaper itself.

Starting from the room’s south wall and working gradually along its width, each of the panels was removed from the ceiling with a Teflon spatula, a flat steel spatula, and a scalpel. As the wallpaper was removed from the ceiling, it was rolled onto a temporary tube to aid handling given the confined space.

As the wallpaper was removed from the ceiling, it was rolled onto a temporary tube to aid handling given the confined space.

As the wallpaper was removed from the ceiling, it was rolled onto a temporary tube to aid handling given the confined space.

While most of the wallpaper was easily removed through purely mechanical efforts, those areas previously protected by the bamboo proved to be stubbornly attached. Given that the media under the bamboo rods exhibited significantly less discoloration than the media that had been completely exposed to the environment, its preservation was of high priority for the project. While the addition of controlled moisture would likely have facilitated the removal in these areas, there was a high risk that introducing moisture would damage the wallpaper’s media. To avoid the potential water damage, the conservators decided to instead skin the wallpaper’s backing paper with a scalpel, though to do so as little as possible. Once the wallpaper had been completely removed from the ceiling, the remaining skinned paper and adhesive was removed locally with dampened cotton and spatulas.

Once the wallpaper had been completely removed from the ceiling, the remaining skinned paper and adhesive was removed locally with dampened cotton and spatulas.

Once the wallpaper had been completely removed from the ceiling, the remaining skinned paper and adhesive was removed locally with dampened cotton and spatulas.

The white surface of the uncovered ceiling consisted of a highly cured, fine-toothed plaster. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, large areas of black mold were discovered once the wallpaper was removed along the southeast glass-paned wall. This mold was weakening the plaster and had severely damaged the wallpaper removed from that area. After discussion and consent from the Jekyll Island Museum curators and staff, it was decided that the affected wallpapers would be disposed of, as the Museum could not store such extensively mold-damaged materials without risk to other collections and staff.

The verso was lightly surface cleaned and any plaster accretions removed.

The verso was lightly surface cleaned and any plaster accretions removed.

The most visually cohesive and least damaged wallpaper panel was selected for treatment at NEDCC. This wallpaper fragment had the verso lightly surface cleaned, any plaster accretions removed, and was re-rolled onto a hard foam cylinder for transport back to NEDCC. The remaining wallpaper panels were lightly surface cleaned on both sides, had accretions removed, and their location noted in reference to the documentation map made prior to removal. These panels were then cut to a manageable size at the request of the Museum, interleaved with Melinex sheets, and housed in oversize folders for permanent storage in the Museum’s archives.

The wallpaper chosen for conservation treatment was then re-rolled onto a hard foam cylinder for transport back to NEDCC.

The wallpaper chosen for conservation treatment was then re-rolled onto a hard foam cylinder for transport back to NEDCC.

The remaining panels were then cut to a manageable size at the request of the Museum, interleaved with Melinex sheets, and housed in oversize folders for permanent storage in the Museum’s archives.

PHASE 2: Treatment of a Single Wallpaper Panel at NEDCC

Photo Documentation

Upon its arrival at NEDCC, the selected section of wallpaper was documented photographically and in writing before it was cut to 40 inches in length, as specified by the Museum. Since the wallpaper in the room would be a facsimile reproduction created by the NEDCC Imaging Services department, the Jekyll Island Museum wanted to have the treated section be of manageable size for display and comparison of the original material to the reproduction wallpaper.

Surface Cleaning and Consolidation

Following documentation, the recto and verso of the chosen section of wallpaper were surface cleaned with brushes and sponges as necessary to further remove remaining surface dirt and embedded grime. The wallpaper’s recto, with its polychrome printed gauze layer, was particularly fragile due to the latter’s failing adhesion in many areas, which was compounded by the media’s flaking and solubility. All friable, loose, flaking, and/or soluble media were consolidated with a 0.5% solution of funori in water. Funori is a polysaccharide mucilage made from the red seaweed (species Gelidium or Gracilaria) and is traditionally used by Japanese scroll mounters; in paper conservation it is used as a consolidant, fixative, and adhesive. This concentration of funori was chosen as it would not alter the surface characteristics of the design and would provide a strong bond while behaving similarly to the media’s original binder material.

Controlled Aqueous Treatment

Further solubility testing was performed on the media following consolidation. The testing confirmed that an aqueous treatment would be ideal because it would remove some of the wallpaper’s irregular discoloration as well as residual adhesive from the verso. However, the testing also indicated that an aqueous treatment required considerable control in the application of moisture to avoid losing media and/or displacing the lightly attached gauze layer.

Blotter Washing

Given these requirements, the conservator chose to blotter wash the panel rather than fully immersing it in a water bath. In blotter washing, the object is first humidified to relax it and is then placed on a stack of wet blotters, with care taken to ensure that the verso of the object is in full contact with the blotters.

This method of washing objects on wet blotters uses gravity and capillary action to remove degraded products (e.g., acidity, staining, etc.) through the verso passively while providing continuous overall support to prevent shifting of the object or its components (e.g., surface media or gauze). Because flowing water is not introduced to the object’s recto, it allows for highly controlled aqueous introduction without solubilizing the media, which could lead to irreversible loss or disfigurement.

Stain Removal

Further stain removal was conducted as needed with a gentle bleaching solution of 3% hydrogen peroxide applied locally using a suction table. A suction table allows for more controlled stain reduction as it allows the bleaching agents to be applied selectively and removed quickly. The applied moisture, whether pure water or a solution, as well as the degradation byproducts and staining agents are actively pulled by suction into the underlying blotters on which the object lies, rather than relying on the more passive capillary action used in blotter washing. This approach is particularly well suited for stain reduction as it removes the moisture at an accelerated rate, thus minimizing contact with the bleaching solutions and more aggressively removing stains.

Mending

Both washing and stain reduction efforts were successful, significantly reducing the previously disfiguring stains and improving the visual coherency of the wallpaper’s design. Following these treatment steps, tears and losses of the two backing papers were filled and mended as necessary with toned Japanese paper and wheat starch paste.

Both washing and stain reduction efforts were successful, significantly reducing the previously disfiguring stains and improving the visual coherency of the wallpaper’s design.

Both washing and stain reduction efforts were successful, significantly reducing the previously disfiguring stains and improving the visual coherency of the wallpaper’s design.

Lining

To encourage the re-adhesion of all three wallpaper layers and provide overall support, the section of wallpaper was lined with a toned, medium-weight Japanese paper and wheat starch paste. With the lining attached, the piece was flattened between blotters under moderate pressure to further encourage adhesion and minimize surface topography. This final step brought the conservation treatment to a successful close.

Framing

After imaging, the conserved wallpaper section was then framed using archival materials and UV filtering glazing in a wooden frame that was reminiscent of the bamboo latticework and selected by the Museum staff.

The wallpaper is on display at Mistletoe Cottage in the conservatory, providing additional context to the Museum's historic preservation efforts as part of their interpretive program. Lined bamboo roller shades, in keeping with original window treatments, will be installed to protect the wallpaper from future UV damage.

After imaging, the conserved wallpaper section was then framed using archival materials and UV filtering glazing in a wooden frame that was reminiscent of the bamboo latticework and selected by the Museum staff.

After imaging, the conserved wallpaper section was then framed using archival materials and UV filtering glazing in a wooden frame that was reminiscent of the bamboo latticework and selected by the Museum staff.

READ PART 2 - DIGITAL IMAGING, DIGITAL RESTORATION, AND REPRODUCTION WALLPAPER PRINTING

LEARN MORE

Jekyll Island, a National Historic Landmark District, The History of Jekyll Island

As of June 2021, special tours of Mistletoe Cottage, highlighting their restoration efforts, have resumed.

Learn more

NEDCC Team

The treating conservators on this project were Luana Maekawa, Suzanne Gramly, and Katie Boodle. Senior Collections Photographer David Joyall assisted with the photographic documentation on-site. He also performed the digitization, digital restoration, and printing of the wallpapers. Jonathan Goodrich, Registrar, provided logistical support.

Kindest thanks to the Jekyll island Museum staff: Rose Marie Kimbell (Archivist and Records Manger), Bruce Piatek (Director of Historic Resources), Taylor Davis (Historic Preservationist), and Andrea Marroquin (Curator). Additional thanks to the special tour guides who, through vivid factual storytelling, brought life to the historic houses and grounds of the Jekyll Island Club.

Party 1 Story by Senior Conservator Luana Maekawa

July 20, 2021