6.1 Obsolescence Monitoring | 6.2 Refreshing and Migration | 6.3 Resources

Section 6: Planning for obsolescence

As this chapter has made clear, managing digital content requires a great deal of planning to ensure that the three-legged stool of organization, resources, and technology remains balanced over time. And, like so much related to digital preservation, this planning cannot stop; it is a long-term commitment to long-term access of digital content. Planning today takes into consideration the needs of tomorrow to ensure that wrappers, codecs, and the media on which digital objects are stored do not obsolesce--and if they do, that there are established pathways for moving them to new formats and media so that they remain accessible over time. (For more information on reformatting, see Chapter 3.) It’s not only formats that obsolesce but also the media on which they are stored and the systems that are required to read or play them. If, for example, an mp3 music file is on a CD ROM but you no longer have a player with which to listen to it, the viability of the file format is only one concern; finding a way to read the media is another complicating factor.

6.1 Obsolescence Monitoring

A fundamental practice of digital preservation is monitoring wrappers, codecs, and media to ensure they remain usable and that they have not become obsolete. Obsolescence can happen at the file or program level (such as Real Media and WordStar) or with the media on which the file is stored (such as Zip drives). When this happens, the digital content becomes unreadable or inaccessible.

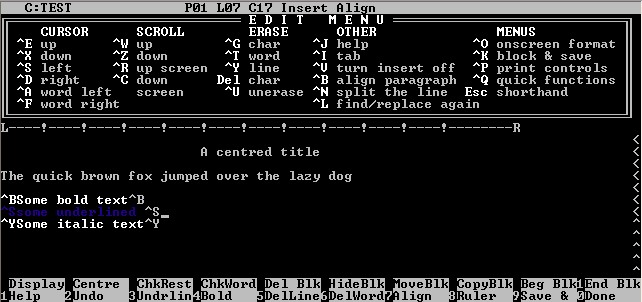

| FIGURE 4.6 An LTO data tape cartridge. A screen shot of Wordstar 4.0. Credit: AVP |

|

Before obsolescence happens, steps can be taken to transition to current storage options or formats, such as Microsoft Word. Keeping track of changes in technology, called “obsolescence monitoring,” involves maintaining awareness of file formats, software, and systems that are ubiquitous (which have less of a chance of becoming obsolete) and, more importantly, awareness of more specialized or less-used formats, which have a greater chance of obsolescence. Monitoring can be accomplished without specialized technologies simply by keeping up with the changing landscape; however, technology-based watch systems are available. Paired with proactive planning, these systems can help ensure that digital content does not become obsolete.

The good news is that obsolescence tends to happen slowly. Routinely reviewing files, conferring with colleagues, and learning about industry-standard formats are some of the best strategies for ongoing obsolescence monitoring.

6.2 Refreshing and Migration

The ultimate goal of digital preservation is the ongoing accessibility of digital content. Think of “content” in this context as you would the moving image on a reel of film. The physical object will change when the film is replaced by a reformatted version stored on digital media, but the content—the images and sound and the order in which they are played—remain the same. Digital audiovisual content must be able to transcend software and hardware changes over time, so choose non-proprietary or “open” formats when possible, such as Broadcast WAV for audio. The media on which digital files are stored will also become obsolete or unstable with age—usually more frequently than file formats do—and those files will need to move to more up-to-date media. Some estimates put the lifespan of hard disk drives at three to five years; others put their median lifespan at six years or more.15 When the risk of loss of digital content due to the threat of obsolescence becomes too great, we look to refreshing and migration.

Refreshing refers to the approach of transferring files and/or data from one media, server, or system to another. This may consist of moving files from an aging server to a new one or shifting metadata from an obsolete database to a more widely used system. Great care must be taken to ensure that all data is transferred in a “lossless” way and that the integrity of the content is verified after the move. Error checking could include running fixity checks on files moved from one server to another, looking for changes or missing files, or reviewing a significant sample of metadata records (10% or more). The frequency with which refreshing happens depends on the technology; data on servers should be refreshed at least every three to five years. Shifts in metadata databases are dependent on the ongoing maintenance of the system in which they are stored.

Migration refers to the transfer of the content and metadata from one audiovisual format, such as a wrapper and/or codec, into another. Migration is necessary when the wrapper/codec or the software used to read the format becomes less ubiquitous and is on the verge of becoming inaccessible. Migration may consist of transferring audio from one wrapper to another without changing the codec, or it may consist of transcoding the audio and placing it in a new wrapper. Real Video, a proprietary video file and encoding format, used to be relatively common for video streaming on the web in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Today the ubiquity of formats like MP4 with h.264 encoding have rendered Real Video practically obsolete. If care is taken to ensure that video and audio are captured at high resolution using stable and open or uncompressed formats, the need to use migration for preservation will be less likely. However, migration, or perhaps the creation of new derivatives from preservation masters, might be required as web trends shift over time.

Because obsolescence can happen at many levels (codec→wrapper→content management system→storage media), refreshing and migration plans must consider all of these: hardware (e.g., servers), software (e.g., video platforms, codecs), and databases (e.g., digital asset management systems [DAMS], collection management systems [CMS]).

Initially selecting the codecs and wrappers, systems, and media with the greatest longevity and openness is ideal and means that refreshing and migration are not immediate concerns. While refreshing and migration are inevitable, being able to postpone that need means you can focus on other aspects of digital preservation management. That isn’t to say that planning should not happen. Identifying funding that will be required when new hardware must be purchased or when staff are hired to complete the process of migration and refreshing helps to future-proof (and disaster proof) digital collections.

6.3. Resources

“Digital Preservation Strategies.” In Digital Preservation Management: Implementing Short-Term Strategies for Long-Term Solutions.

https://dpworkshop.org/dpm-eng/terminology/strategies.html

“Obsolescence: File Formats and Software.” In Digital Preservation Management: Implementing Short-Term Strategies for Long-Term Solutions.

https://dpworkshop.org/dpm-eng/oldmedia/index.html

Sustainability of Digital Formats: Planning for Library of Congress Collections. http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/formats/intro/intro.shtml

Section 7: Prioritization and Phasing ›