PART 1 – The Preservation Catch-22

by Katie Boodle, NEDCC Associate Paper Conservator, 2020

In 2019, NEDCC worked on conserving the State of South Carolina’s seven Constitutions, along with a certified copy of the 1790 Constitution. This project followed closely on the heels of NEDCC’s treatment of Alabama’s six Constitutions in preparation for the Alabama bicentennial. While the South Carolina Department of Archives and History was not preparing for an exhibition, they were concerned with how prior restoration techniques were affecting some of the State’s most important documents.

Because of the vastly different nature of the treatment for the parchment and the paper documents, as well as the complex history of Barrow Lamination in libraries and archives, this story has been split into two parts. For information about the parchment-based Constitutions, see Part 2—Devoured: When Mold Attacks!

Time, Travel, and Temperament

The South Carolina Constitutions have a storied history that was reflected in their previous condition. The documents were believed to have been kept in the busy port city of Charleston at least until the Civil War Era,  despite Columbia being established as the capital in 1790. After the Civil War in 1865, the state’s records and offices in Charleston and Columbia were combined and moved into the newly built State House that still sits at the center of Columbia today. While the State House was a secure and durable building, its storage facilities were lacking in any sort of environmental control. It wasn’t until 1940, after the 1776 Constitution was rediscovered, that the state’s Historical Commission, the group that would become the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), took custody of the documents.

despite Columbia being established as the capital in 1790. After the Civil War in 1865, the state’s records and offices in Charleston and Columbia were combined and moved into the newly built State House that still sits at the center of Columbia today. While the State House was a secure and durable building, its storage facilities were lacking in any sort of environmental control. It wasn’t until 1940, after the 1776 Constitution was rediscovered, that the state’s Historical Commission, the group that would become the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), took custody of the documents.

(“New State House at Columbia, South Carolina,” Engraving, 1860. Richland Public Library)

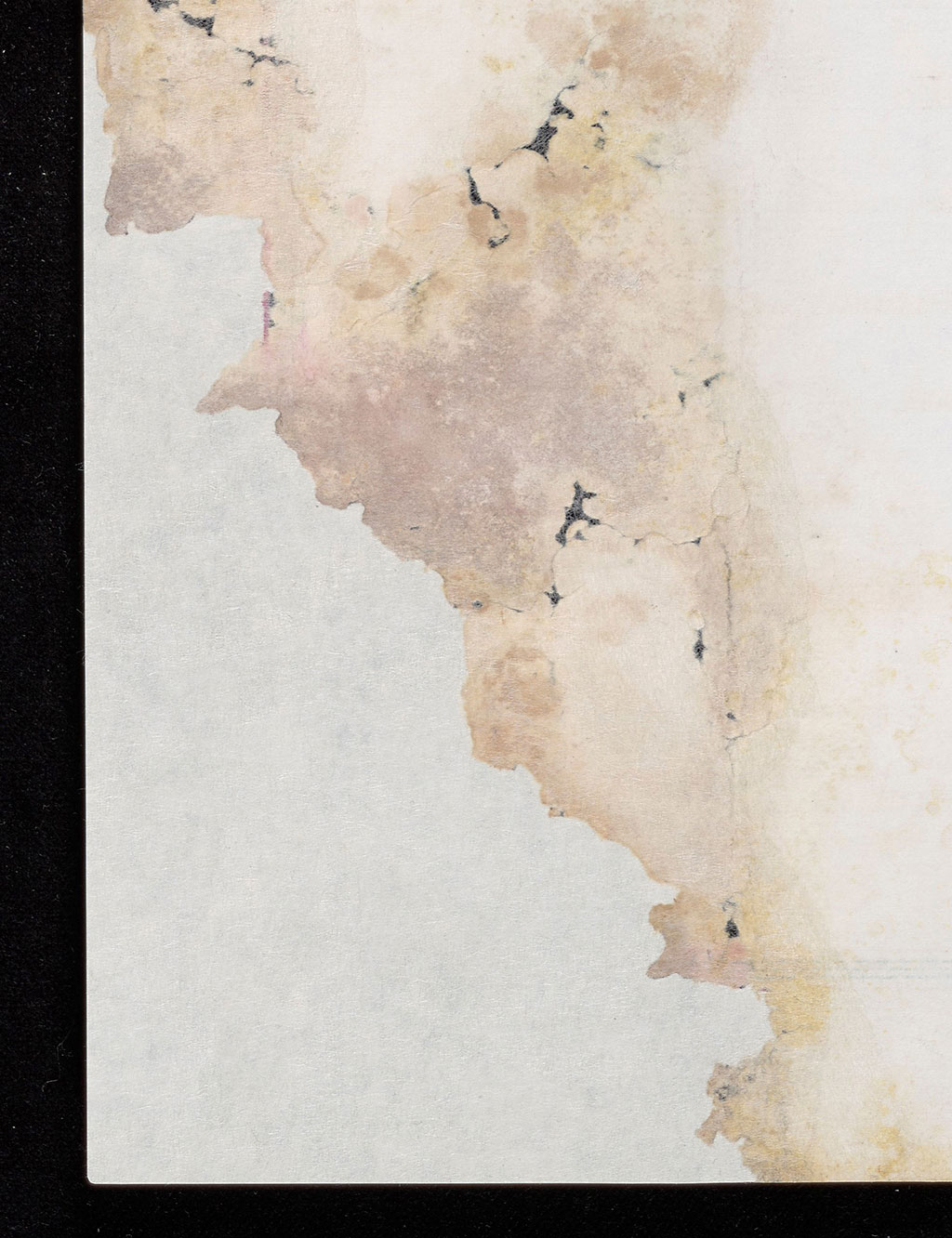

The Constitutions all had distinct patterns of damage that came from their storage conditions and obscure placement in the State House. Many of the items showed overall weakening of their substrate from increased acidity and degradation. In a few, large losses were present from previous mishandling and/or insect activity. Some showed evidence of tidelines from damp conditions where condensation or free flowing water had affected the object. In some cases, the humid conditions encouraged mold damage, which compounded the issue of lost material and further weakened the paper structure.

The damage to the paper-based Constitutions also had the additional complication of having gone through a treatment known as “Barrow Lamination,” a process in which a paper-based object is sealed between two sheets of cellulose acetate film and tissue. While SCDAH did most of their Barrow Lamination in-house after 1950, they were still susceptible to the various improvements that Barrow made to his method through in its history. This led to a significant difference in appearance and effects of the method on each of the Constitutions.

The damage to the paper-based Constitutions also had the additional complication of having gone through a treatment known as “Barrow Lamination,” a process in which a paper-based object is sealed between two sheets of cellulose acetate film and tissue. While SCDAH did most of their Barrow Lamination in-house after 1950, they were still susceptible to the various improvements that Barrow made to his method through in its history. This led to a significant difference in appearance and effects of the method on each of the Constitutions.

[Photo: William J. Barrow demonstrating his method of de-acidification to SC Historical Commission staff members Louise Caughman (left) and Wylma Wates (right) during his 1953 trip to Columbia to install his lamination machine. Ms. Caughman would operate the lamination machine for the next several years.]

Lamination in Archives: A Brief History

Cellulose acetate lamination has had a long and complicated place in libraries and archives considering just how briefly it was used compared to other techniques. The thought process behind moving towards lamination as a stabilizing preservation technique is not even terribly surprising when looking back at its historical development. Prior to the invention of cellulose acetate, other lamination-like techniques were used to repair and restore historic materials. The most commonly used and widely spread was silking which dates back to the mid-1700s in some form or another. While not a lamination in the modern sense, it does nonetheless enclose an item between two sheets of an open weave silk using paste or an animal-based adhesive to provide overall support.

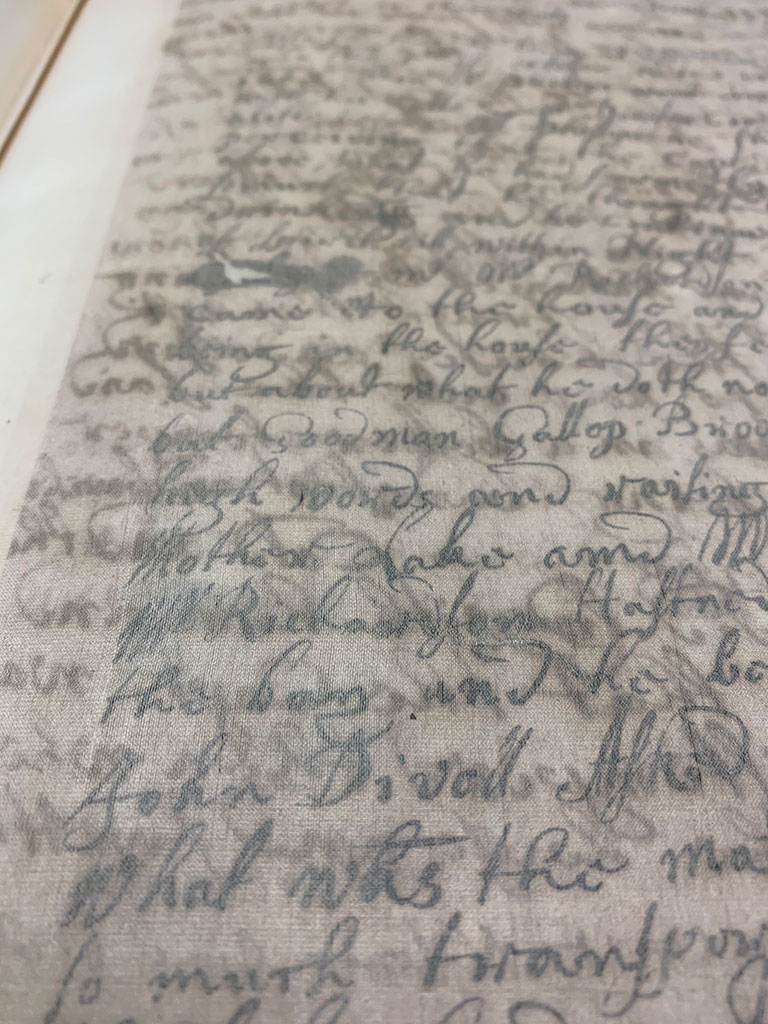

Example of a silked document

Example of a silked document

Building from this method in the early 1890s, Francis Walcott Reed Emery, a book binder from Taunton, MA, began laminating documents and books with both silk and tissue. He eventually changed his process enough from the older technique by adding a paraffin wax coating and benzene to gain patent rights for the method. This became known as the Emery Process and was considered to be a standard preservation treatment by many archives and collections until its decline in the 1930s.

Example of Emery Lamination

Example of Emery Lamination

While part of the decline of the Emery Process can be attributed to concerns rising around the long-term stability of the paraffin and silk, the development of plastics was a game changer to the field of lamination. The thermoplastic properties of cellulose acetate meant that it could be applied without much fuss and, once heated, would set rapidly, increasing the volume of material that could be completed in a single day compared to other techniques. William Barrow saw the advantages of being able to meet not only the demand for document stabilization, but also provide a cost effective and potential in-house alternative to other techniques.

Barrow began his work in the mid-1930s on creating this heat-set lamination as a complement to his on-going research in the field of paper chemistry. Given his background, it is no surprise therefore that Barrow’s laminations were exclusively done with tissue, rather than silk or a combination of the two. He set-up shop in Richmond, VA and worked to establish his reputation along with a relationship with the many State and Federal institutions in the area. The Virginia State Library’s support in particular was instrumental in helping Barrow move forward. While it took some time to perfect his methods, by 1942 Barrow had not only finally acquired a patent for his technique, but also for his lamination machine.

Barrow Lamination on the 1776 Constitution under magnification

To many archivists, Barrow’s work seemed like a lifesaver and was highly regarded as the gold standard within the archives. That’s not to say that the process didn’t have problems or that Barrow himself wasn’t a controversial figure. Barrow is regarded by some as the first person to significantly promote awareness about the issues of paper acidity. However, some question just how much of his research and work was original, along with the reliability of his testing methods. Barrow was aware of some of the pitfalls of the cellulose-acetate lamination and, at least to some extent, that creating a sealed environment for materials that would essentially self-destruct over time. As early as 1940, he employed various deacidification methods prior to laminating material, even going so far as to try and deacidify the cellulose acetate film.

Unfortunately, despite Barrow’s efforts, most of the issues come from the cellulose acetate itself or from overly deacidifying to the point that the pH of the paper has become so alkaline that it is just as problematic as if it were too acidic. The high pH can cause a breakdown of the size, soften the paper, and break down media in unpredictable ways. The cellulose acetate can create such a strong bond that, when combined with softened paper, actually causes the paper to split and pull apart, leaving two separate pages adhered to the supporting tissue. The strength of the bond and eventual embrittlement of the cellulose acetate and tissue can cause significant surface breaks and chipping of the materials, as seen above under magnification. This can result in skinning or text loss in extreme cases.

Avoiding this damage is desired by archivists and conservators alike--but here is the Catch-22. In “An Epidemic in the Archives: A Layman’s Guide to Cellulose Acetate Lamination,” by Eddie Woodward, we see just how the lamination process was able to help save some collections that would otherwise not still exist to undergo treatment now that we know more about paper chemistry and the materials. Given the condition and history of some of the Constitutions, it could be argued that it is thanks to the Department’s in-house lamination investment that these materials still exist and are not in significantly worse shape.

The other part of the Catch-22 is that some of the later cellulose acetate laminations do not show the same level of degradation as Barrow’s earlier attempts. Given the cost, risks, and hazards associated with removing the lamination, as well as our own strides in understanding and creating new techniques, conservators and archivists must weigh whether or not lamination removal is immediately necessary for a single document or a whole collection.

In the case of the South Carolina Constitutions, the answer was easily agreed upon that now was the time to address the issues associated with the lamination by NEDCC and SCDAH staff. As well as having the issues described above, the lamination tissue was not just used to laminate the material, but also used as a fill for many losses. This resulted in extensive distortion in most of the earlier documents. The documents were also much larger than the available lamination sheets resulting in a local overlapping area that created a centralized cupping of the paper on the 1778 Constitution.

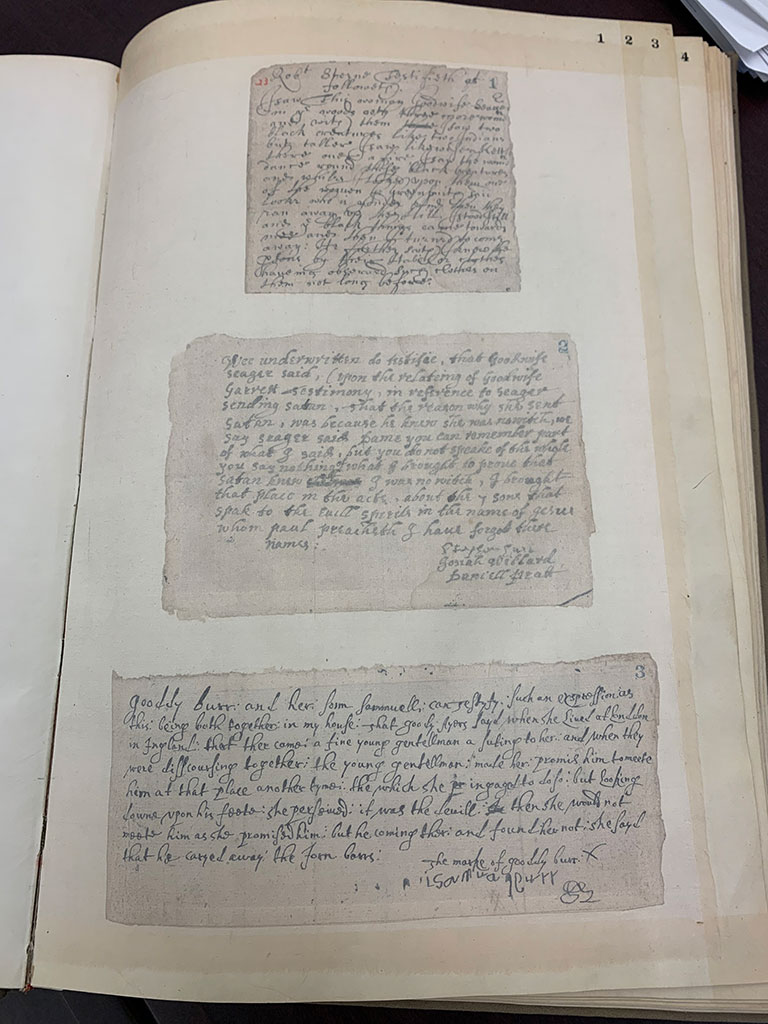

Exterior paper wrapper of 1778 Constitution

“Like Dissolves Like”

In cellulose acetate lamination, there is not an adhesive present in the traditional sense, but rather the film is acting as the adhesive layer thanks to its thermoplastic properties. In many ways, this makes the process similar to a pressure sensitive tape, e.g. cellophane tape, and it is treated as such when it comes to removal. There is some variation in what will actually dissolve the cellulose acetate for each piece as one has to factor in cross-linking, recipe changes, and environment. However, we traditionally turn to the polar solvents—ethanol, acetone, and water—with the goal of completely solubilizing the cellulose acetate into the solution. By mixing these in various percentages, a suitable solution can be found for each object to both remove the lamination and prevent any damage to the media.

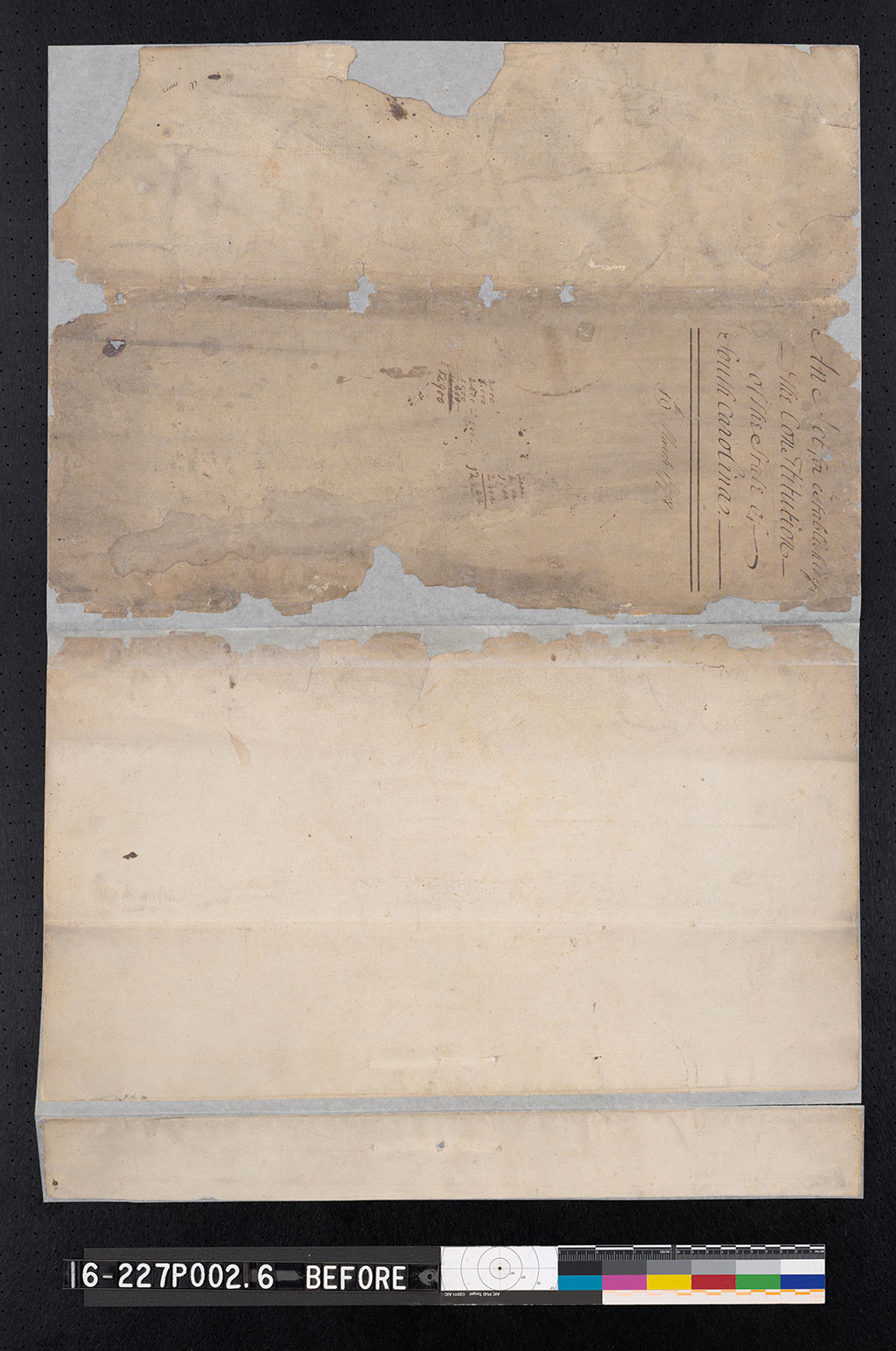

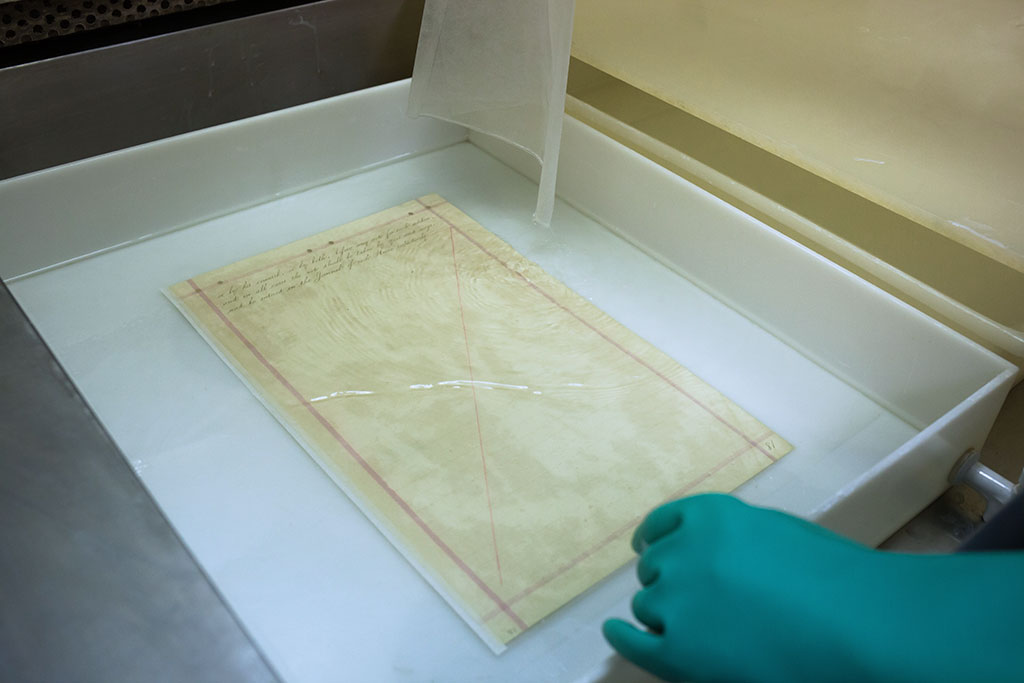

Initial immersion into a solvent bath

Media was a particular concern for removing the lamination on the 1895 Constitution. There was a significant amount of two different types red and blue ink that could not be properly tested with the lamination layer in place. While they seemed to be stable during local solvent testing, the treating conservators were still suspicious that there could be complications during the solvent baths due to an incomplete dissolving of the lamination adhesive locally. After discussing the potential for media bleed with the SCDAH staff, a single page that had all four of the ink types, but very little text was chosen and approved for more intensive testing.

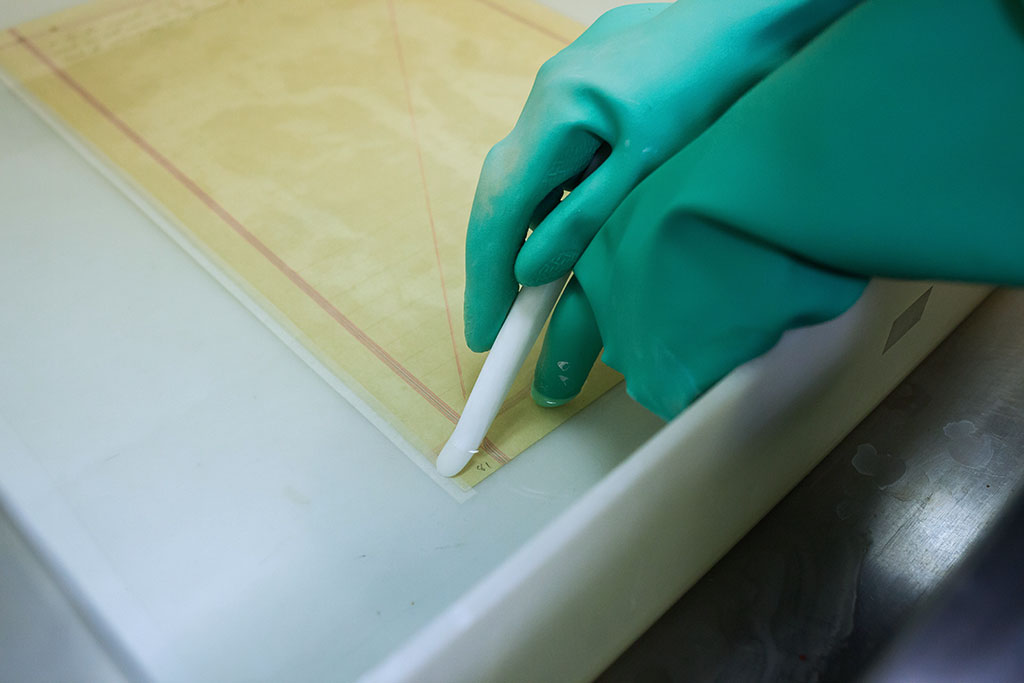

Removing top layer of lamination tissue

Removing top layer of lamination tissue

Removing lamination stub material from binding edge

After a short period of time, the tissue layer floated off with ease and the media remained unaffected. Some mechanical separation needed to be performed to remove a slightly thicker lamination paper stub that was present along the binding edge, but overall, the treatment was considered successful and safe to perform on the remaining pages of the volume.

Conservator checking small fragment for adhesive haze

Most of the material needed to be immersed in at least one more solvent bath and some needed to be immersed in a third due to the degradation of the lamination and number of sheets used to create a fill. Pieces were allowed to partially dry as conservators looked for a characteristic white haze that comes with dissolving the cellulose acetate layer, thus indicating the presence of residual adhesive. If no haze was present, the pieces could be moved to a filtered water or water and ethanol bath, depending on what the media required.

Testing for iron gall ink degradation

The documents were tested for the presence of free iron ions in addition to standard solubility tests to see if a calcium phytate treatment needed to be performed rather than a standard aqueous treatment. These ions are present in degraded iron gall ink and are usually more prevalent in very acidic conditions. The calcium phytate treatment helps stabilize the ink and limit further degradation to the media. Fortunately, none of the objects required it, most likely due to the near neutral or slightly high pH of most of the papers. This pH was a good indication that the deacidification performed prior to lamination was well done.

Discoloration from acidic and degraded products removed from the 1776 constitution

When possible, aqueous treatment was performed shortly after the lamination material was removed. Many of the pieces released a significant amount of discoloration and did not feel as brittle after this treatment.

The Devil in the Details

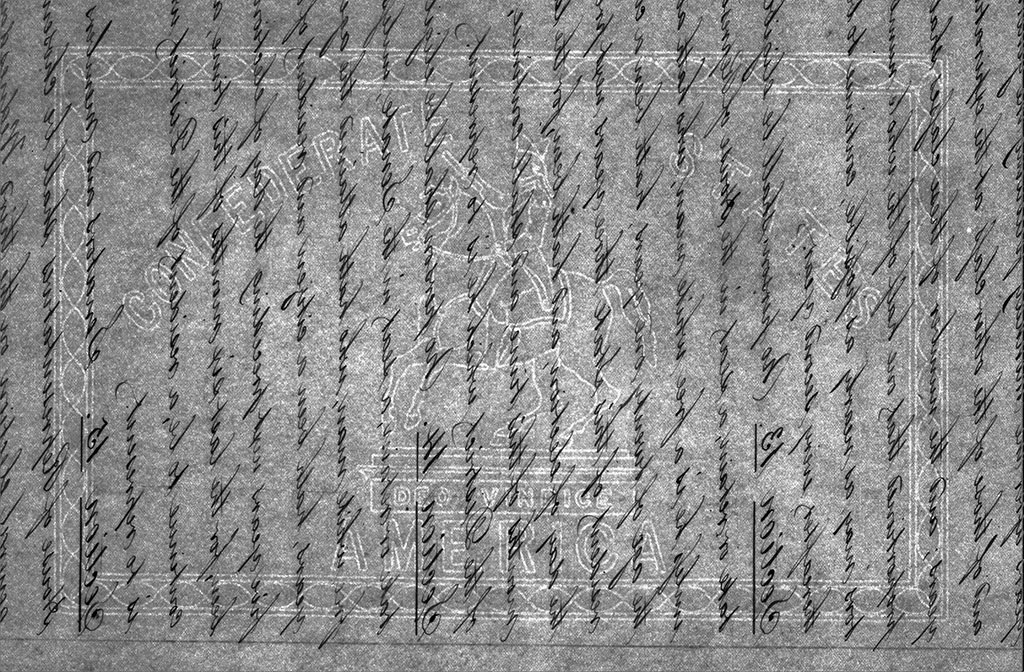

Once the paper-based Constitutions had been treated aqueously and sized with methyl cellulose or gelatin to return some strength to the weakened paper, mending and filling was performed. The papers for the South Carolina Constitutions were very distinctive in that they were either very smooth or had very strong screen impressions from the paper making process. The papers from the 1865 constitution were of particular interest as they had a very specific watermark for the Confederate States of America, indicating that the paper was created in the South during the Civil War.

Watermark of the 1865 Constitution

Watermark of the 1865 Constitution

In the case of the very smooth wove papers, using a lighter weight, slick Japanese gampi paper was found to provide the exact surface and support necessary on each piece. For the laid papers, however, a bit more care had to be put into the fills. The 1776 constitution had the most extensive losses and breaks. In order to create a good visual continuity, paper weight, tone, and the chain and laid lines were taken into consideration. A local papermaker’s handmade paper was deemed suitable for the purposes of the fills.

Matching chain and laid lines for fills on the 1776 Constitution on a light box

Both papers were wet out to fully expand the paper structure. After putting down a sheet of polyester to work upon, the fill paper was then matched up and shaped to the size and shape of each loss. The fill was then pre-mended to the original paper with wheat starch paste and a medium weight Japanese kozo. The constitution was lined overall with a light weight Japanese kozo paper for support of both the original paper and the fill.

Placing paper for filling

Placing paper for filling

Precision shaping paper over 1776 constitution with a layer of polyester between the paper and the object

Precision shaping paper over 1776 constitution with a layer of polyester between the paper and the object

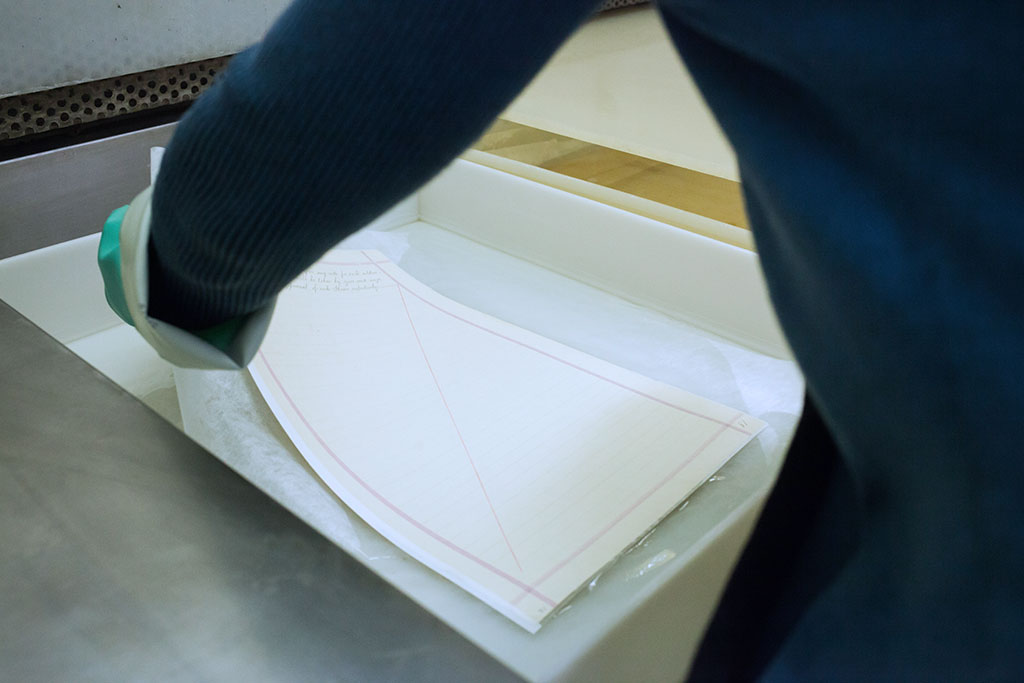

Removing polyester support during lining of 1776 Constitution

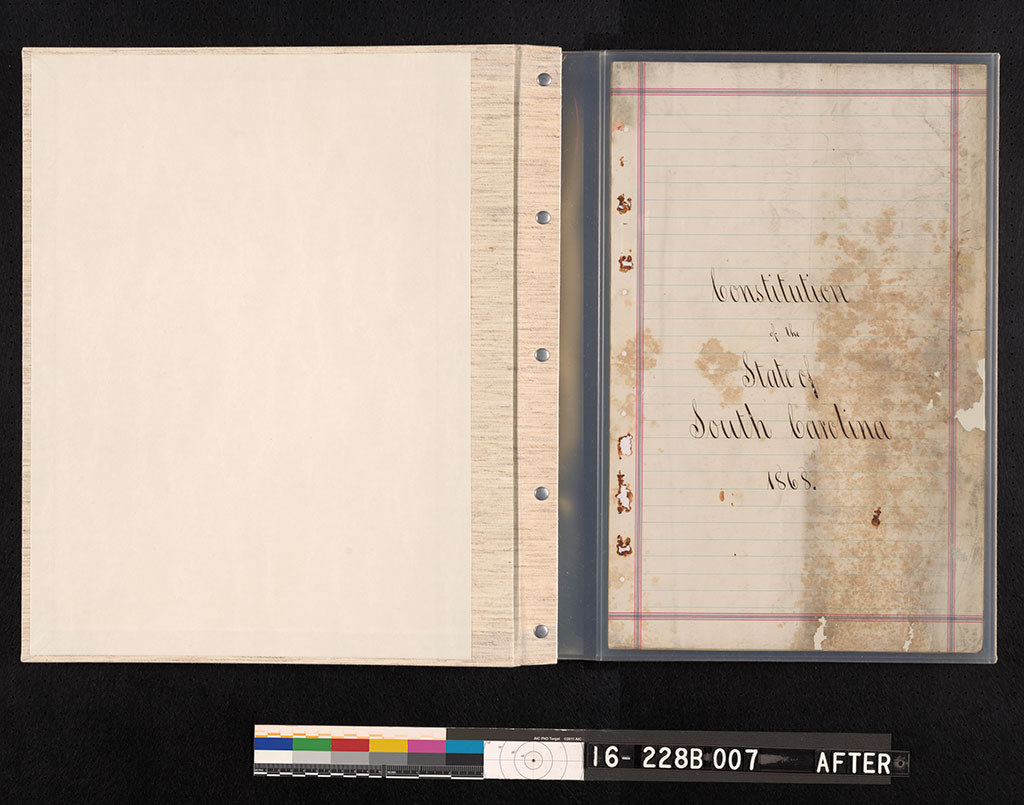

Along with having to match the laid paper, delicate selective mends had to be applied to the 1868 constitution where mold damage had occurred in the lower right corner and along the fore edge. The paper was deemed to be too weak to support an attached fill after further examination. In areas of large corner losses, the fill was trimmed precisely to the edge of the damaged area and the light weight Japanese paper acted as the primary support for both the fill and the damage. In areas where there were small losses, only the light weight tissue was applied.

Details of filing and mending on the 1868 Constitution

This Constitution could not undergo aqueous treatment or be sized like some of the other objects, due to extensive ink solubility issues and paper weakening. As the constitution was being encapsulated and returned to a post-bound format as requested by the client, there was no concern that the mends needed to be extensive as the polyester supporting material would offer sufficient protection to each page.

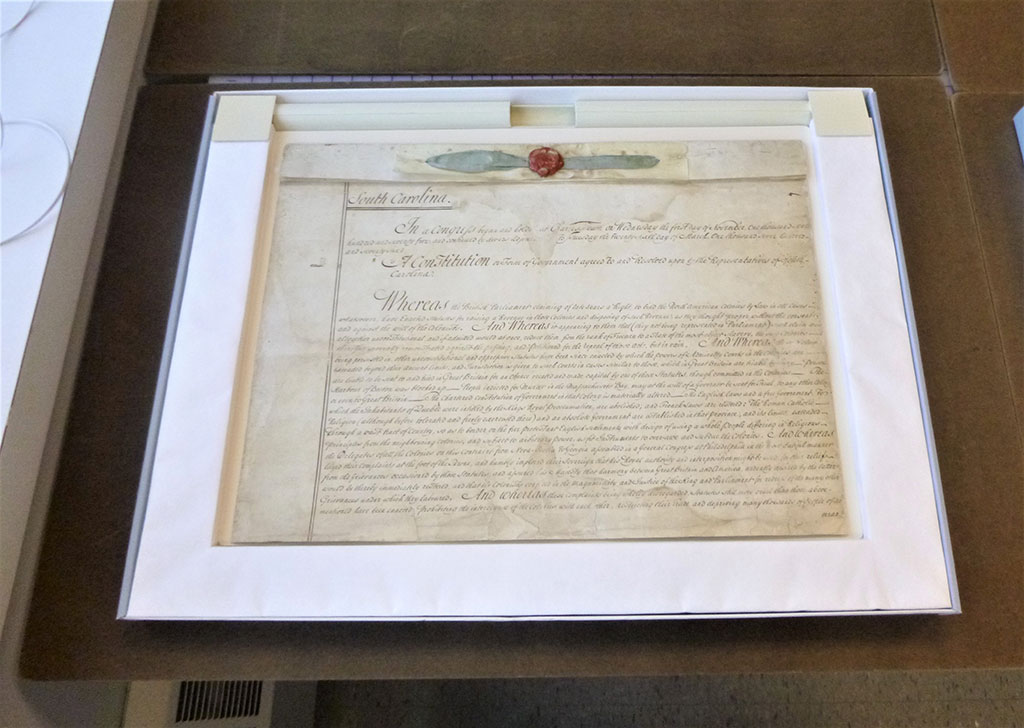

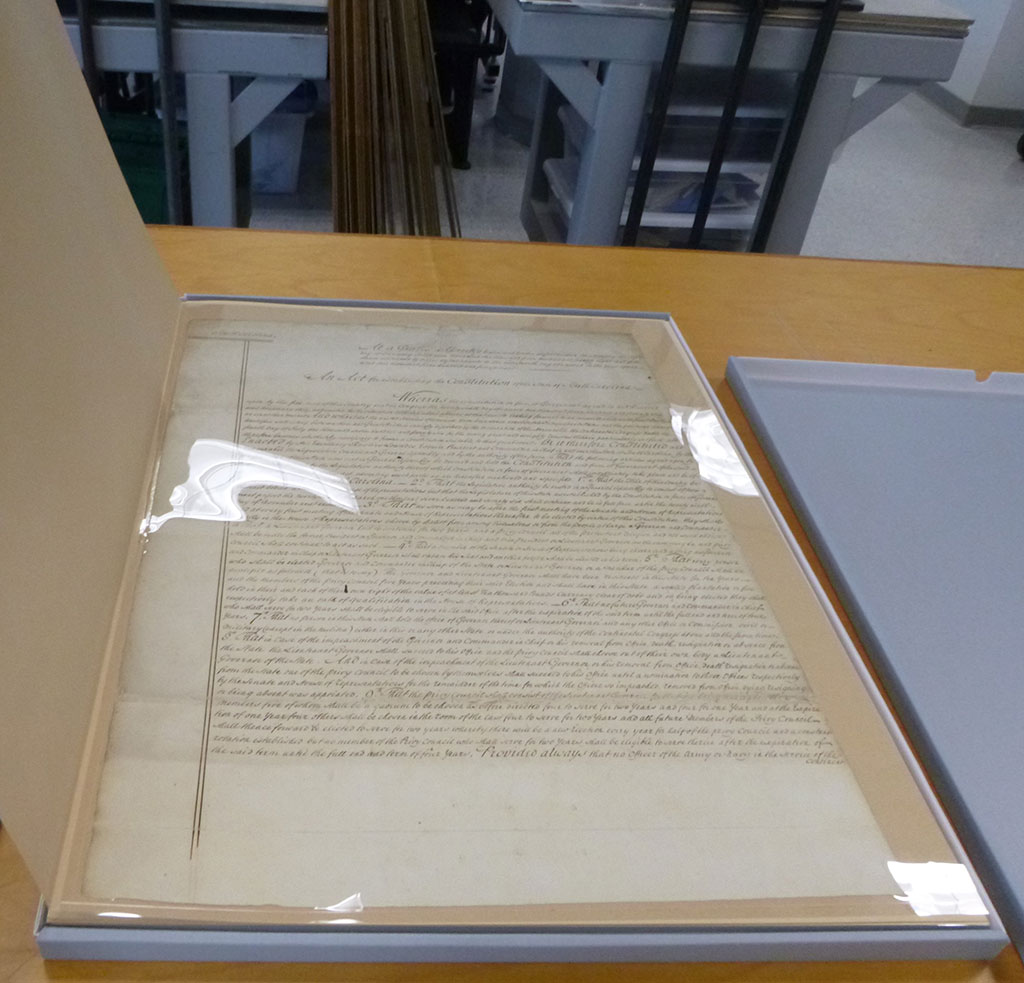

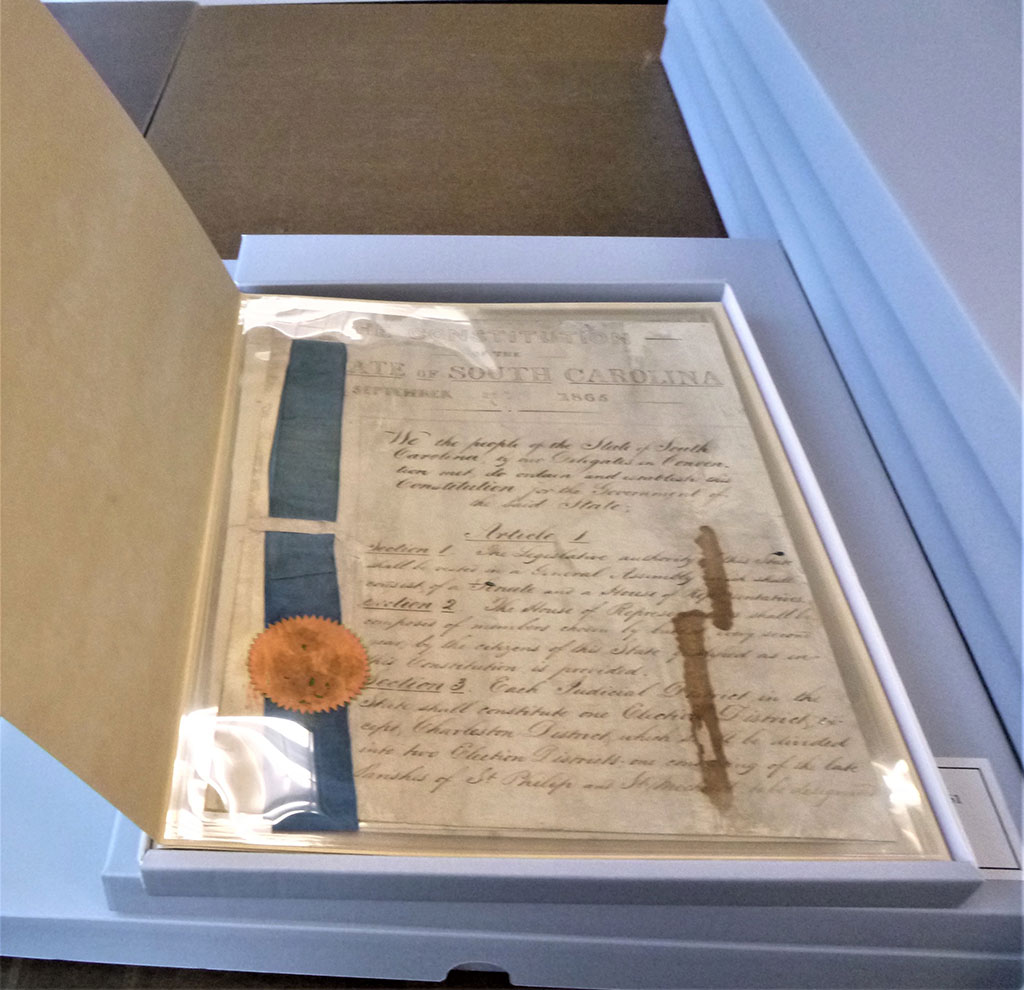

Creation of Customized Housings

The 1776, 1778, and 1865 Constitutions were rehoused in polyester L-sleeves, archival folders, and custom fit archival boxes. In the case of the 1776 Constitution, the box was constructed to accommodate a support tube that would protect the seal when the Constitution was viewed and prevented the paper from creasing if folded over too far. The box was also built out to accommodate the varied height of the document. The 1776 Constitution was also strapped to a 100% 8-ply cotton rag board with polyester to aid in handling, but also make it easy to slide out if the archive wished to display it in a different manner.

1776 Constitution in the custom fit box

1778 Constitution foldered and boxed for return

1865 Constitution foldered and boxed for return

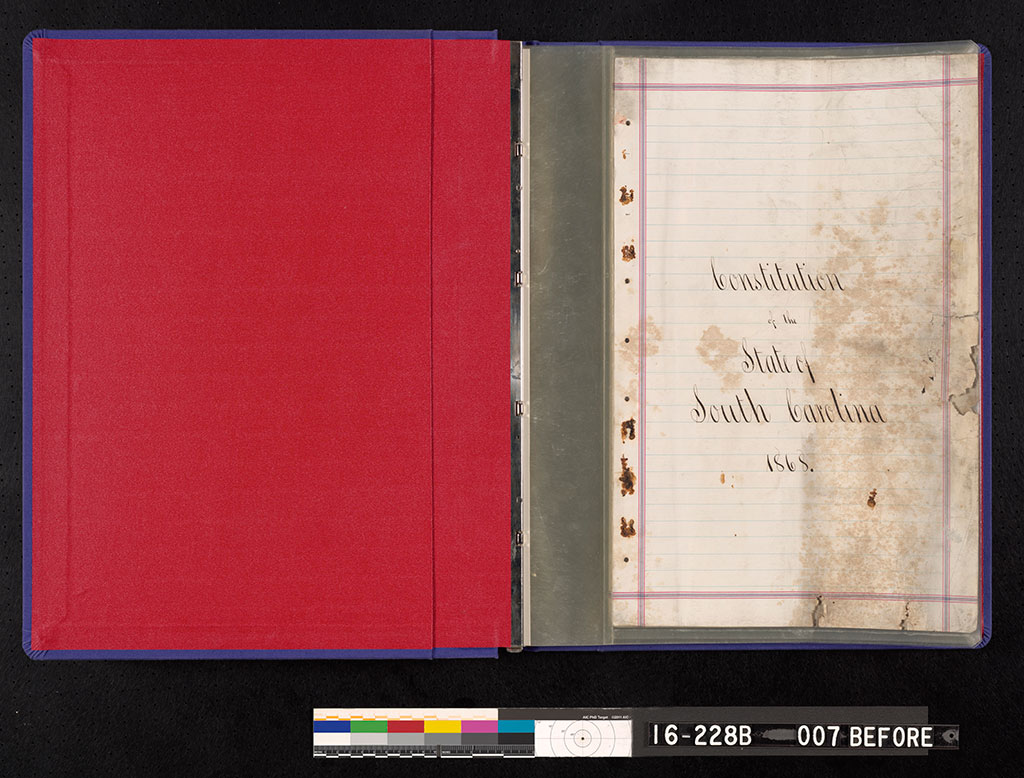

The 1868 and 1895 Constitutions were originally bound in two very different and extremely heavy post bindings upon arrival at NEDCC. After treatment, new matching post bindings of a more appropriate size were constructed for the two Constitutions. The new post bindings were also constructed in such a way that the individual sheets were spaced out to prevent crimping or buckling of the polyester and paper.

Example of encapsulating a document during post-binding construction with spacers

Example of encapsulating a document during post-binding construction with spacers

A sheet of microchamber paper was also inserted behind each piece as a pre-emptive measure to mitigate the formulation of a microclimate and absorb any acidic material that may develop over time.

Original post binding on the 1868 Constitution

Original post binding on the 1868 Constitution

Post binding on the 1868 Constitution after treatment

Conclusion

After treatment, the documents were returned home by aircraft of the South Carolina Aeronautical Commission accompanied by two SCDAH staff members. While at present there are no plans to display the material for an extended period, access will be greatly improved through availability of the high-quality digital copies.

Coming Soon!

Watch for the NEDCC story Part 2 — Devoured: When Mold Attacks! for the rest of the story on the conservation of the parchment documents.

Thanks

Many thanks to Dr. Eric Emerson and Patrick McCawley for their help on this story and throughout the treatment of the Constitutions. Additional thanks to the South Carolina Legislature and Governor Henry McMaster for providing funds for the historic preservation of these important documents.

LEARN MORE

Want even more Information on the South Carolina Constitutions?

Visit The Silver Crescent Standard’s article by archivist Patrick McCawley, “Preserving South Carolina’s  State Constitutions,” which discusses the history of the documents and the archives, along with logistics from the archives' point of view.

State Constitutions,” which discusses the history of the documents and the archives, along with logistics from the archives' point of view.

While you're there check out the other great blog posts about the South Carolina collections, on-going exhibitions, and interesting research projects.

Visit the South Carolina Department of Archives and History Online, on Twitter, or Facebook.

Story Notes

More information on the history of cellulose-acetate lamination can be found in Eddie Woodward’s 2017 article, “An Epidemic in the Archives: A Layman’s Guide to Cellulose Acetate Lamination.”

Additional Information on William Barrow can be found in Sally Roggia’s 1999 Doctoral Thesis “William James Barrow: A Biographical Study of His Formative Years and His Role in the History of Library and Archives Conservation From 1931 to 1941.”

Additional information on the history of lamination, its development, and an early history of paper conservation can be found in Christine Smith’s 2016 book Yours Respectfully, William Berwick: Paper Conservation in the United States and Western Europe, 1800 to 1935.

NEDCC Project Team

The treating conservators on this project were Katie Boodle, Terra Huber, Suzanne Gramly, Mary French, and Jessica Henze. Specialized housings were created by Annajean Hamel and Ned Shultz. Collections Photographers David Joyall and Tim Gurczak assisted with the photographic documentation that was used throughout this article.

Story by Katie Boodle, Associate Paper Conservator, 2020