Part 2 – Devoured: When Mold Attacks!

by Katie Boodle, NEDCC Associate Paper Conservator

In 2019, NEDCC worked on conserving the State of South Carolina’s seven Constitutions, along with a certified copy of the 1790 Constitution. This project followed closely on the heels of NEDCC’s treatment of Alabama’s six Constitutions in preparation for the Alabama bicentennial. While the South Carolina Department of Archives and History was not preparing for an exhibition, they were concerned with how prior restoration techniques were affecting some of the State’s most important documents.

Because of the vastly different nature of the treatment for the parchment and the paper documents, as well as the complex history of Barrow Lamination in libraries and archives, this story has been split into two parts. For information about the paper-based Constitutions, see the NEDCC story Part 1—The Preservation Catch-22. Part 2 will primarily cover the treatment of the 1861 Constitution, with some of the treatment on the two 1790 Constitutions included in relevant locations.

Time, Travel, and Temperament

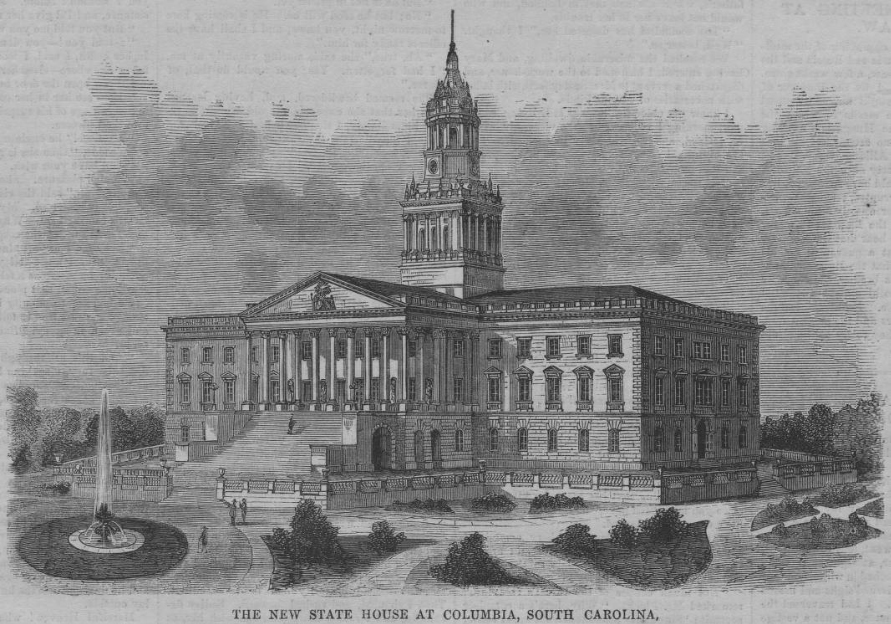

The South Carolina Constitutions have a storied history that was reflected in their previous condition. The documents were believed to have been kept in the busy port city of Charleston at least until the Civil War Era,  despite Columbia being established as the capital in 1790. After the Civil War in 1865, the state’s records and offices in Charleston and Columbia were combined and moved into the newly built State House that still sits at the center of Columbia today. While the State House was a secure and durable building, its storage facilities were lacking in any sort of environmental control. It wasn’t until 1940, after the 1776 Constitution was rediscovered, that the state’s Historical Commission, the group that would become the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), took custody of the documents.

despite Columbia being established as the capital in 1790. After the Civil War in 1865, the state’s records and offices in Charleston and Columbia were combined and moved into the newly built State House that still sits at the center of Columbia today. While the State House was a secure and durable building, its storage facilities were lacking in any sort of environmental control. It wasn’t until 1940, after the 1776 Constitution was rediscovered, that the state’s Historical Commission, the group that would become the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), took custody of the documents.

(“New State House at Columbia, South Carolina,” Engraving, 1860. Richland Public Library)

The Constitutions all had distinct patterns of damage that came from their storage conditions and obscure placement in the State House. Many of the items showed overall weakening of their substrate from increased acidity and degradation. In a few, large losses were present from previous mishandling and/or insect activity. Some showed evidence of tidelines from damp conditions where condensation or free flowing water had affected the object. In some cases, the humid conditions encouraged mold damage, which compounded the issue of lost material and further weakened the paper structure.

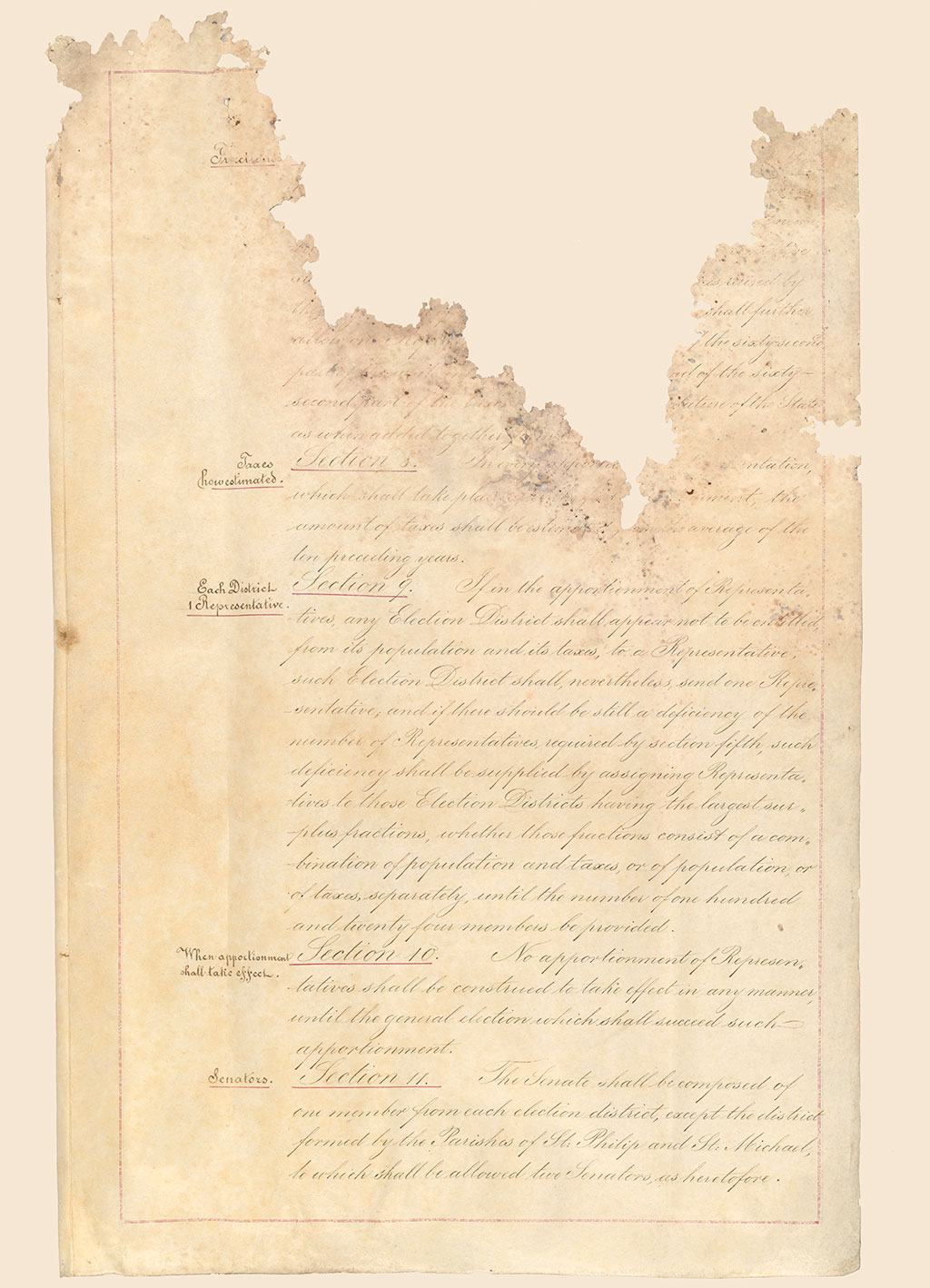

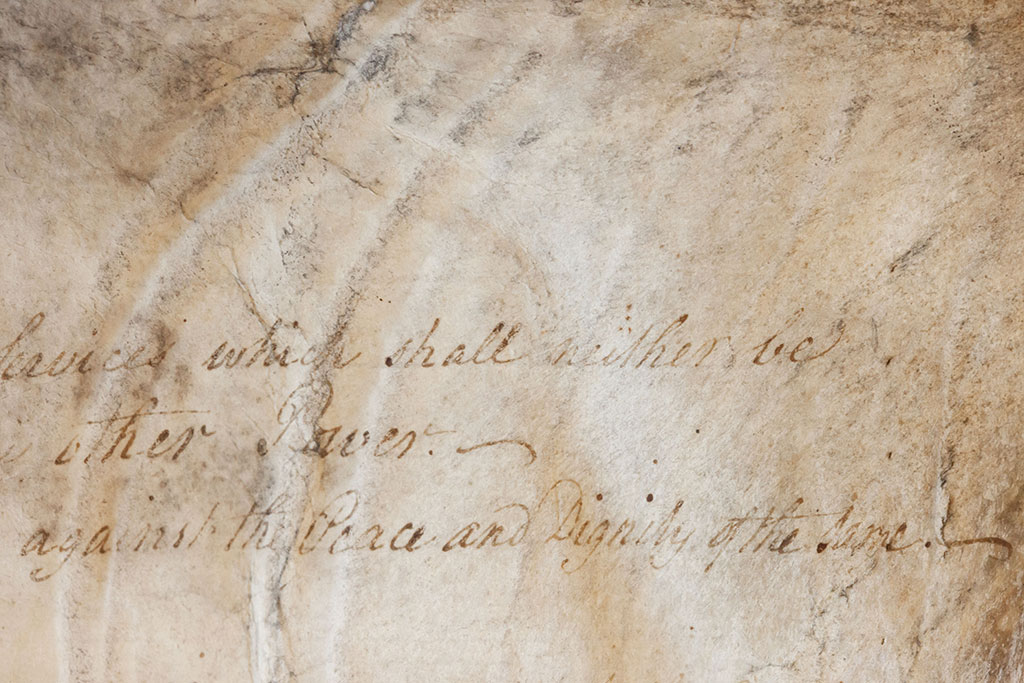

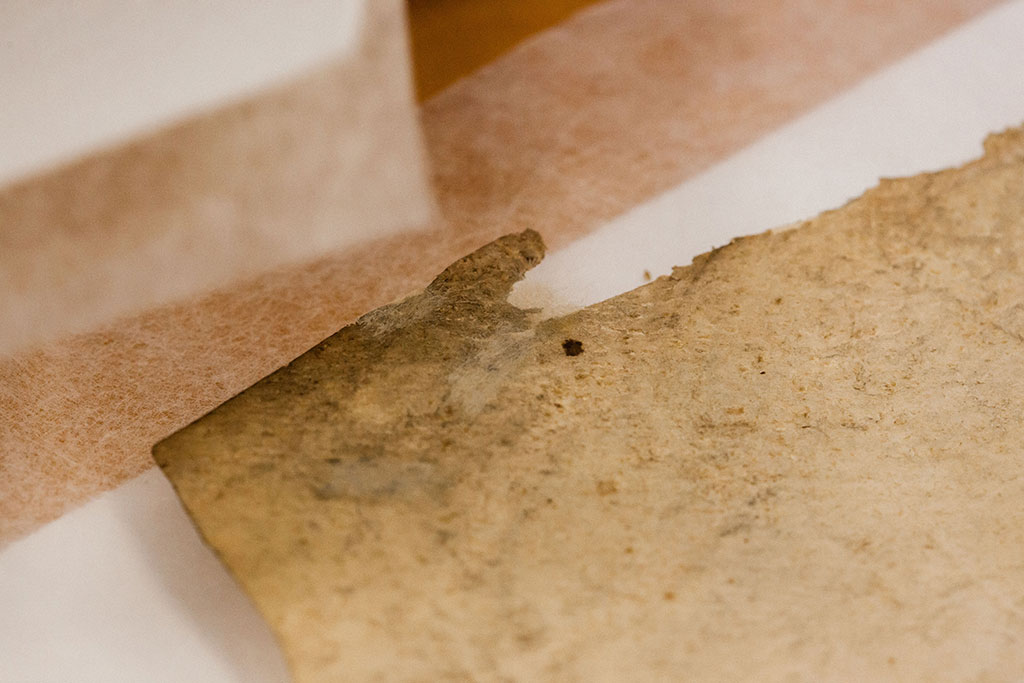

Of the three parchment Constitutions, the 1861 Constitution, written shortly after the state’s secession, was the most damaged. The whole document has been severely mold-damaged in the upper half with large losses to the substrate and overall weakening of the parchment support. The losses came not only from the mold growth, but also from insect activity which thinned the already delicate support and, in some places, laminated pieces together. The overall result was a document that could not be safely accessed.

Mold and insect damage to the 1861 Constitution

Mold and insect damage to the 1861 Constitution

Dealing with Mold and Insect Damage

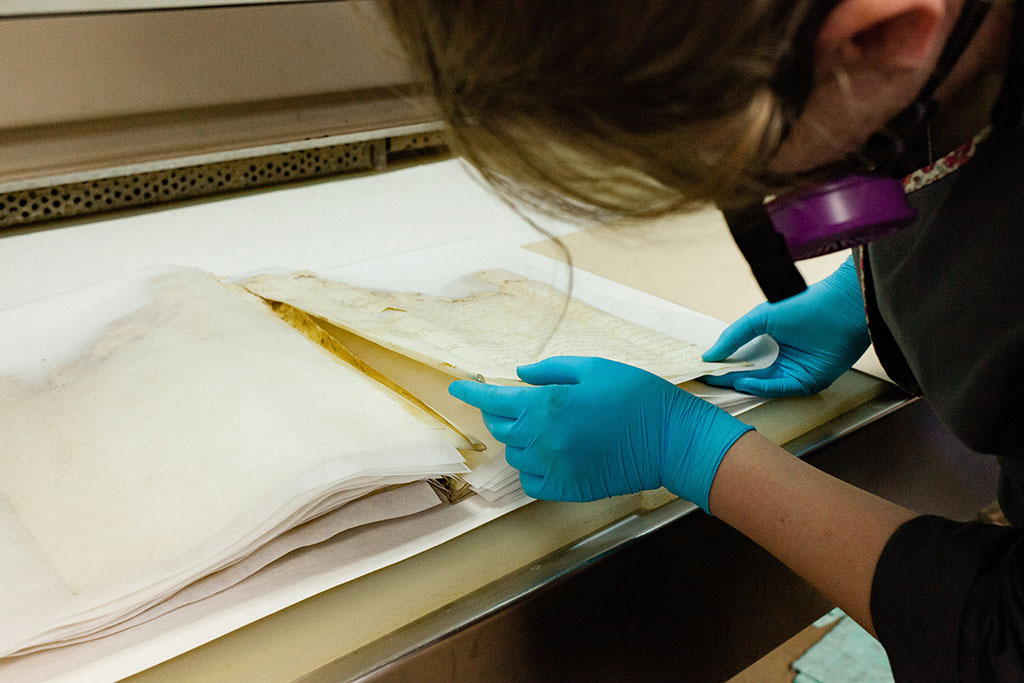

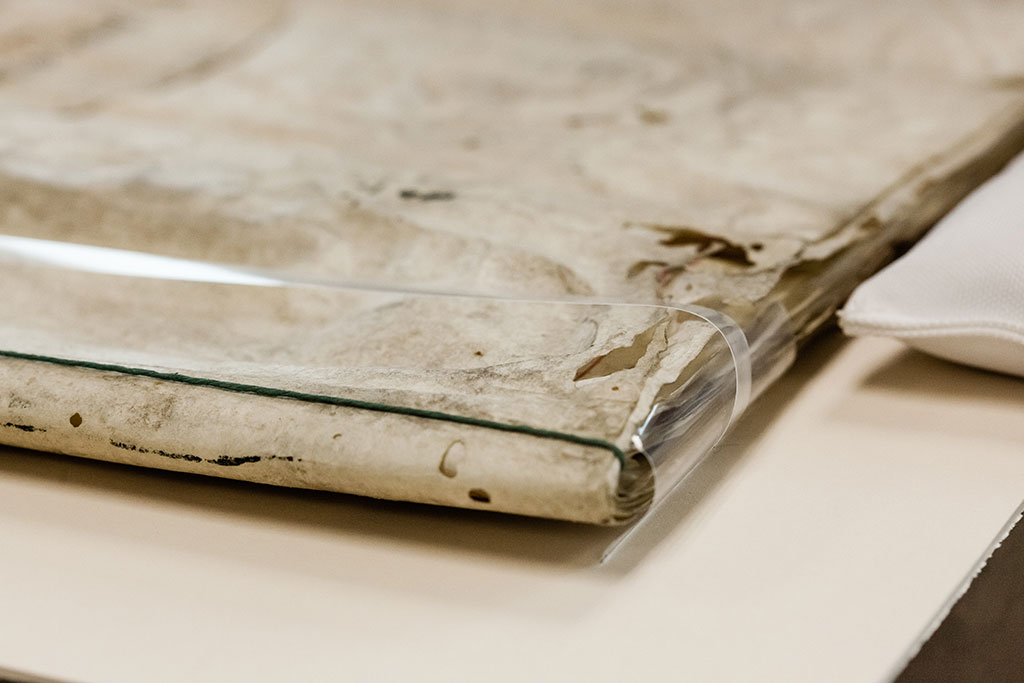

Given the extensive damage to the 1861 Constitution and how it was assembled, it was determined that the document needed to be separated into individual bifolia in order to stabilized weakened areas properly. The Constitution was first interleaved with a thick, smooth Hollytex™ that would provide support to weakened areas as much as possible and not catch on the delicate edges. The document had two layers of sewing that needed to be carefully removed. The first was a tight-fitting and very frayed green silk ribbon.

Cutting the frayed ribbon locally

As there was some uncertainty about the alignment of the sewing holes, the lack of excess ribbon around the tie location, and the damaged substrate, the ribbon was cut next to the tie. The ribbon was then removed slowly with tweezers, watching to ensure that it did not catch and break along the parchment.

Removing the ribbon from the sewing holes

The second layer of sewing was a fine binding thread comparable to a 30/3 linen thread. It too was cut near the securing tie of the pamphlet stitch and carefully removed. After this was complete, the bifolia and single leaves could be accurately collated and separated from one another for treatment.

Separating interleaved bifolia

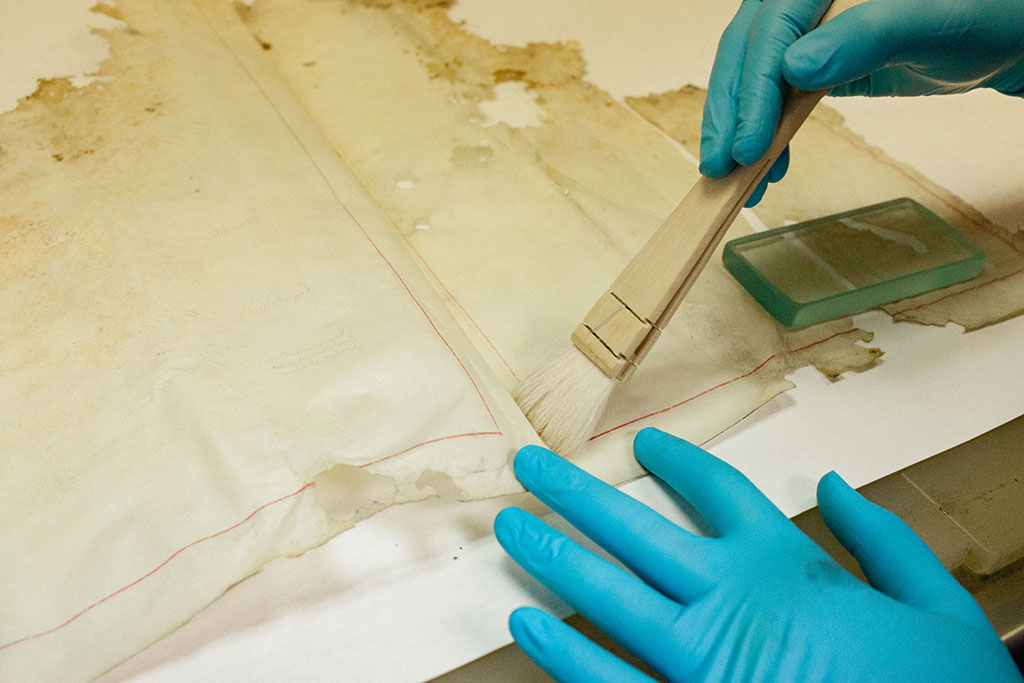

Surprisingly, a significant amount of text was found to be intact in areas where the parchment had not been mold-damaged. In damaged areas, the media was minimally to moderately friable. Luckily, the mold was inactive rather than live at this point. Surface cleaning and mold remediation techniques were carried out with soft brushes and small-pore non-latex sponges to remove a majority of the inactive spores, taking care to avoid removing any of the friable media. A HEPA vacuum with a fine point suction was used sparingly to remove any larger spores present, given the media and substrate concerns.

Surface cleaning at gutters with hake brush

Surface cleaning at gutters with hake brush

Local mold remediation with non-latex sponge

Local mold remediation with non-latex sponge

After remediation and cleaning, the initial Hollytex™ was swapped out with new, clean Hollytex™ and each bifolio or single leaf was placed in its own collated folder. The folders were separated into two groups—stable media and friable media—in preparation for consolidation. The media was consolidated with a mixture of ethanol and gelatin applied under magnification.

Individually foldering cleaned bifolia

Separate, Secure, and Stabilize

Localized area of lamination and distortion

The parchment on all of the Constitutions had large areas of loss and fragility that needed to be selectively stabilized to improve handling for imaging and reassembly. In the case of the 1861 Constitution, some areas had to be separated from where they had become laminated together due to crushing and distortion of the layers. To repair these areas, needle-nose tweezers and a very small Teflon spatula were used to lift, separate, and manipulate pieces back into alignment as needed. Light pressure was applied along the creased areas to burnish the folds and flatten them in areas of severe distortion.

Realignment of distortion

After realigning and flattening the eaten edges, small strategic suture mends were attached to lightly hold the fragile pieces in place. In cases where the parchment narrowed dangerously, the floating fragments were given a second anchor point, or bridge, to the closest large area of the parchment.

Applying suture and bridge mends on floating fragments

It was chosen to not insert fills on the parchment documents for several reasons. On the 1861 parchment, there was significant concern that the damaged areas would not be able to support the weight of even a light fill. On the 1790 Constitutions, the fact that they were full skins, complete with strong axilla, and already had very distinct distortions, raised concerns that creating large fills could pull the parchment in undesirable ways. The 1790 Constitutions were therefore strategically repaired with a slightly heavier paper than the 1861 document, but still with the purpose of focusing on stabilizing areas that could catch or become a handling issue.

Example of local damage and stains on 1790 Constitutions

Example of strong axilla marks on 1790 Constitutions

Example of strong axilla marks on 1790 Constitutions

Strategic mends on the 1790 Constitutions

Furthermore, some of the 'losses' in the skins were fly-holes created during the parchment making process. As these are considered to be a natural part of the parchment, they are never filled during conservation treatment. Tears around the fly-holes, however, were stabilized as necessary using the same manner as before.

Stabilizing repair near a fly-hole on the 1790 Constitution

Access for the Inaccessible

Given the severe amount of mold damage to the 1861 constitution, it was surprising to both NEDCC and Archives staff that a significant amount of text was still legible. However, as mentioned before, the document was not easily accessible without significant care. Because of this, the decision was made to digitize the 1861 Constitution in its entirety and create a print facsimile for research use at the SCDAH.

Setting up for digitization

Due to the delicate nature of the mold damaged bifolia, two photographers were required, one who focused exclusively on handling and staging the bifolia during image capture, and a second who operated the camera and monitored image quality of each captured page before moving on to the next. By having two photographers in place, the object was handled as little as possible and with extreme care to the delicate areas.

Preparing to digitize the interior of a bifolio

After capture and post-processing, the bifolia were cropped to single pages and a color fill was dropped into the background. A neutral, sympathetic tone for the background fill was selected by sampling the color from an area of the parchment in relatively good condition. These background fills eliminated shadows and other visual distractions in the facsimile’s presentation. Without this color tone, the paper would have otherwise been a bright white.

Example of page for facsimile print

Each of the prints was checked against the original bifolia prior to the reassembly of the Constitution for color matching and then printed on Moab's Moenkoip Washi Kozo™ archival inkjet paper and trimmed to size. The prints were placed in L-sleeves, foldered and boxed for in-person research use.

1861 facsimile prints foldered and boxed for easy access

Creation of Customized Housings

Despite treatment, the 1861 Constitution was too fragile to be handled either as a whole piece or as individual bifolia. After much discussion with the client, a more permanent, spacious solution was chosen over encapsulating the document. To best protect the piece, a deep sink mat and sealed package were constructed. Given the irregular shape of the Constitution, it needed to be float-mounted rather than having the mat overlap and potentially apply pressure to any weak areas. To suspend the document in place, slits were cut in a 4-ply rag board backing just under where the edges of the document would lie.

Cutting slits in 4-ply rag board for polyethylene strapping

Cutting slits in 4-ply rag board for polyethylene strapping

The Constitution was then aligned on the backing and its placement was checked to confirm that it would be square once the strapping was laced through.

Aligning the 1861 Constitution on the backing board

Two layers of polyethylene strapping were inserted into the lower slits. The interior was a 2” wide strap that would act as the primary support for the piece. A ½” wide polyethylene strap was then laced through to hold the cover sheet in place. When typically using the strapping for mounting, the smaller strapping is only used at the fore edge; however, in this case it was used at both the spine and fore edge. This was required due to some vertical damage near the sewing that was causing the cover to fall forward in this area.

Lacing of the primary and secondary strapping supports at the spine edge

Detail of layered strapping at spine edge

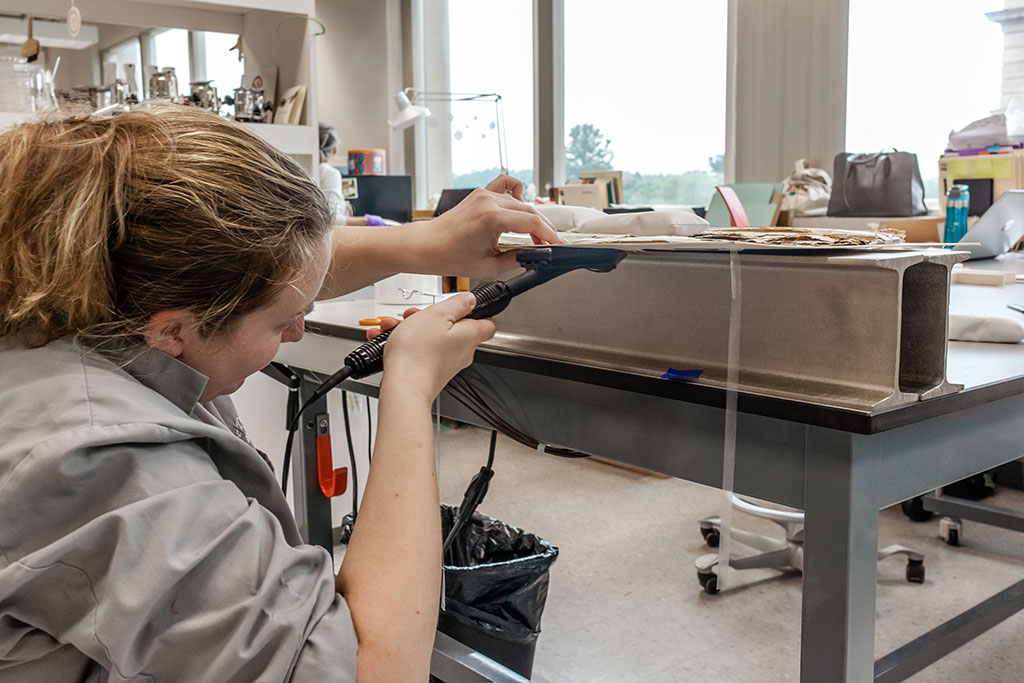

The polyethylene was tensioned lightly to ensure that the Constitution would remain tight against the board without crushing or damaging any delicate parts. It was then heat welded to itself on the verso one strap at a time with a tacking iron.

Heat welding polyethylene straps on verso

Tensioning, attachment, and overall support of the document was then tested by holding the mounted document at various angles until was finally upright. While a vertical position for this piece was not recommended, it was important to ensure that the attachment would hold and not pull at the damaged areas in case it was temporarily or accidentally placed vertically.

Testing vertical security of strapping

The sealed package was then assembled with rag board, Coroplast™, and a reduced reflection and anti-static UV acrylic.

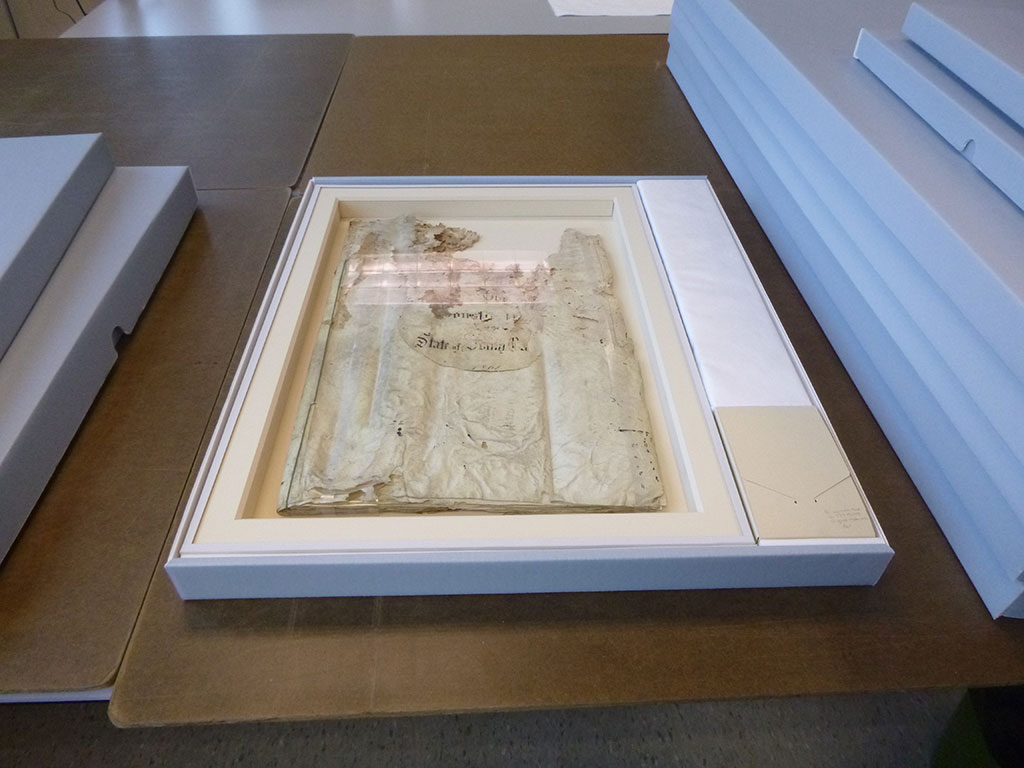

Sealed package of the 1861 Constitution in an archival box with original sewing materials at the lower right

Conclusion

After treatment, the documents were returned home by aircraft of the South Carolina Aeronautical Commission accompanied by two SCDAH staff members. While at present there are no plans to display the material for an extended period, access will be greatly improved through availability of the high-quality digital copies.

See the NEDCC story Part 1—The Preservation Catch-22 for the rest of the story on the conservation of the paper documents.

Thanks

Many thanks to Dr. Eric Emerson and Patrick McCawley for their help on this story and throughout the treatment of the Constitutions. Additional thanks to the South Carolina Legislature and Governor Henry McMaster for providing funds for the preservation of these important documents.

LEARN MORE

Want even more Information on the South Carolina Constitutions?

Visit The Silver Crescent Standard’s article by archivist Patrick McCawley, “Preserving South Carolina’s  State Constitutions,” which discusses the history of the documents and the archives, along with logistics from the archives' point of view.

State Constitutions,” which discusses the history of the documents and the archives, along with logistics from the archives' point of view.

While you're there check out the other great blog posts about the South Carolina collections, on-going exhibitions, and interesting research projects.

Visit the South Carolina Department of Archives and History Online, on Twitter, or Facebook.

NEDCC Team

The treating conservators on this project were Katie Boodle, Terra Huber, Suzanne Gramly, Mary French, and Jessica Henze. Specialized housings were created by Annajean Hamel and Ned Shultz. Collections Photographers David Joyall and Tim Gurczak assisted with the photographic documentation that was used throughout this article as well as digitization of the constitutions.

Story by Katie Boodle, Associate Paper Conservator, 2020